Voices of Resistance, Voices of Transcendence:

Musicians as Models of the Poetic - Political Imagination

Marsha Baxter

The Crane School of Music

State University of New York at Potsdam, U.S.A.

Citation: Baxter, M. (2010). Voices of resistance, voices of transcendence: Musicians as models of the poetic - political imagination. International Journal of

Education & the Arts, 11(Portrayal 3). Retrieved [date] from http://www.ijea.org/v11p3/.

Abstract

How might songs, like John Lennon's Imagine or Bob Dylan's Blowin' in the wind, offer ways to explore alternative ways of

being in the world, to challenge the status quo? How might these songs become springboards for original pieces that capture students' ideas about world issues? In this article,

I observe what happens when selected strategies from an on-going curricular writing project utilizing a social justice framework are presented to a class of New York City fifth graders.

I draw from student-created songs, instrumental compositions, written and video-taped narratives to document ways in which these elementary school students embrace ideals of social

responsibility through music-making.

Visual Abstract

Introduction

You know what Lenin said about Beethoven's Appassionata. "If I keep listening to it, I won't finish the revolution."

-- Georg (Von Donnersmarck, 2007)

Recording of Beethoven's Appassionata

Lenin's words, quoted by the character Georg in Von Donnersmarck's film, The lives of others, convey music's capacity to stir a sense of humanity that transcends, even denies,

conflict and revolution. When silenced by news of the suicide of his beloved friend, the blacklisted director Jerska, Georg proceeds to the piano and plays Sonata for

a good man. He recites Lenin's words and asks, "Can anyone who has heard this music, I mean truly heard it, really be a bad person?" The

camera cuts to the attic surveillance post, where the Stasi agent Wiesler, through headphones, eavesdrops on the wire-tapped performance. His eyes radiate a rush of

emotion that tell us, yes, he has heard. Von Donnersmarck's cinematic example invites us to consider what a piece of music, such as Sonata for a good man, or a

painting, like Picasso's Guernica, can do that a political debate or summit cannot.

This study explores expressions of social awareness and critique in musical works by folk, rock, and Latin jazz composers and considers their potential to open spaces for

critical reflection, dialogue, and creativity in the music classroom. The particular examples are drawn from an on-going curricular writing project as my undergraduate and graduate

students and I work toward developing a social justice framework in a global music education course (Baxter, 2007). In the role of facilitator, I observe what happens when

selected strategies authored by my university students are shared with a class of fifth graders in a New York City public elementary school. I draw from student-created work,

written and video-taped narratives to document ways in which these elementary school students embrace and/or resist ideas and ideals of social justice.

Theoretical Framework

Central to our project is the notion that the arts can be powerful agents for developing social imagination (Greene, 1995, 2001). Greene defines social imagination as the "capacity to invent visions of what should be and what might be in our deficient society, on the streets where we live, in our schools" (1995, p. 5). Active, meaningful encounters with art works may counter the habitual, the familiar and move us to envision a more humane society and world.

Imagination creates openings for the empathetic (Greene, 1995, p. 3). Empathy, writes Greene, signifies the "capacity to see through another's eyes, to grasp the world as it looks and sounds and feels from the vantage point of another" (2001, p. 102). Imagination enables us to glimpse the grim, unspeakable realities of a detention camp, captured in Guantanamo (Washburne, 2006, track 6), a small combo work I recently performed with the Crane Latin Ensemble.

Recording of Guantanamo

The opening unison trumpet, tenor saxophone, and trombone lines seem to cry out, to wail a

musical lament built upon a succession of ascending minor triads. The pan-diatonic sonorities

of the improvisatory middle section in an Afro-rhythmic groove create a sense of friction, of

agitation. As the opening lament returns, and the closing melodic lines, now in canon, descend

to a hollow unison G, we come to sense the harsh crimes of neglect, of invisibility suffered by

the prisoners. At the final cadence in the musical score, Washburne instructs performers to

"Deconstruct into the silent oblivion of the masses" (Washburne, 2003).

Teachers, like artists, have the responsibility to question and challenge the historical and

social realities around them. Paulo Freire (2007) underlines the ethical responsibility of

progressive educators to disclose conditions of oppression. It is our obligation, he argues, to

develop ways to understand the realities of politics and history in order to enact change (p. 3).

At the heart of our inquiry and creative process is the concept of being more. For Freire, being

more signifies "our capacity to expand our humanity" (2007, p. xxi); his conception arises

from an ontological matrix of struggle, which he defines as an orientation - historical and

social - of human nature to be more (1996, p. 159). What does it mean to be more as a music

educator? Music instruction, with Freire's principles in mind, invites daring contemplation

and action. "Human activity," he writes, "consists of action and reflection: it is praxis" (1970,

p. 106). The consequence of praxis for Freire is action upon and naming one's world. From

this vantage point, songs and instrumental works become vehicles for exposing and critiquing

injustice. In turn, these encounters may lead students to respond, through original words and

music, to the inequities they witness in their communities and world.

Project Design

If the fight gets hot, the songs get hotter. If the going gets tough, the songs get tougher.

-- Woody Guthrie (Telonidis, 2007)

What happens when we ask students to contemplate the lyrics of John Lennon's song Imagine

or Chris Washburne's Latin jazz instrumental work Pink? How might attending to these works

help students to name alternative ways of being in the world? How might these encounters

become springboards for original pieces that capture and articulate their developing world view? In what ways might music curricula centered on themes of justice,

equity and fairness become a catalyst for nurturing social consciousness?

I returned to PS 87, an elementary school on Manhattan's Upper Westside where I had taught

general music for over a decade, to pilot our ideas for probing these questions. The school's

environment of creativity, interdisciplinary collaboration, and community activism resonated

with the aims and content of our social justice strategies. The music teacher, Matthew,

expressed an eagerness to pilot the proposed curricular strategies and recommended Joyce's

fifth grade class - Class 5B-302 - as our participants1.

Guiding the class collaborative project authored by my undergraduate students were the

questions:

* How might music curricula foster ideals of equity and social justice?

* What kinds of classroom musical experiences might deepen an understanding and valuing

of social justice?

We explored these questions within a multicultural music education paradigm, in which

teachers and learners work to understand alternative perspectives and to develop cultural

sensitivity. We also understood school curriculum as non-neutral knowledge (Apple, 2000;

Freire, 1996; Giroux and Shannon, 1997). Dialogue and questioning became central to

exposing and critiquing issues of social justice in our work. For example, in exploring issues

of censorship and musical oppression in the strategy The noteless song of oppression: Music

in Afghanistan, the authors invite students to consider the following: "Do you think that a

musician could ever be a fugitive from the law? How would you feel if the government

stopped musicians from performing? Would you have a difficult time connecting with your

culture if it could not be expressed musically?" (Baxter, 2007, p. 273).

Matthew, Joyce, and I met to chart the direction and content of our collaboration, seeking

ways the strategies designed by my undergraduate and graduate students might complement

curricula in the fifth grade classroom. As a New York City public elementary school teacher,

Joyce must follow a city-wide mandated writing curriculum. She suggested scheduling the

music project to overlap with the curriculum's poetry unit, an idea that proved insightful.

As the project unfolded, I became responsible for presenting most of the music listening

strategies, while Matthew took charge of the compositional process during, as well as outside,

regularly scheduled music classes. Joyce guided the creative and analysis process in the fifth

grade classroom, as students composed poems, lyrics and analyzed songs with political and

social narratives.

The curricular strategies, intended to complement an existing music program, centered upon

topics frequently avoided and/or marginalized in music curricula. We invited students to

articulate an artist's viewpoint regarding a social and/or political issue; to become familiar

with a composer's musical vocabulary, to explore why a particular style and/or genre

effectively communicates an artist's thoughts; to look at covers and performance contexts of

works; and to challenge their own beliefs about society and history. Students were invited to

respond to what they believed is the most pressing issue in our world through an art form of

their choice. In an accompanying artist statement, students detailed ideas and issues they

confronted and artistic devices they employed.

Curricular strategies designed by my undergraduate and graduate students became

investigative models, while musical repertory around which the strategies were created

changed. The classroom teacher, music teachers and I selected musical examples during the

initial and middle phases of the project. Toward the project's end, students began to bring

songs with social narratives to critique with their peers.

Beginning Conversations

The fifth graders deposited their backpacks along the celadon-tiled hallway wall and filed into

the music room for their weekly music class and first lesson of our social justice project. As

we sat facing each other in the carpeted central meeting area, framed by rows of electronic

pianos on one side and shiny black fiberglass congas on the other, I felt the familiar tinges of

nervous energy that I still experience on the first day of classes. I explained that I wanted to

know how they thought about issues in the world, and how they, as composers, might express

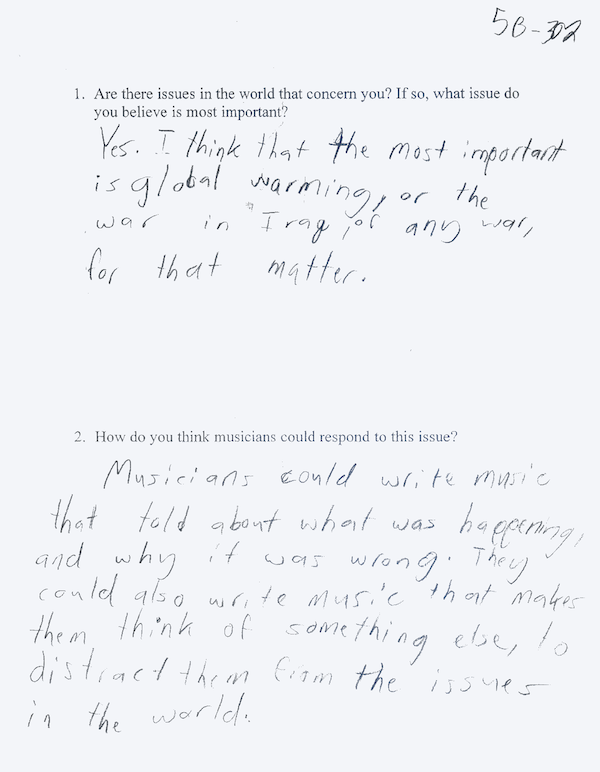

their ideas through music. Our conversation began by sharing their written responses to three

questions:

Students cited global warming as the issue they believe to be most important. Most students

listed multiple issues of concern that, together with global warming, included war - in

particular, the war in Iraq - and pollution; illegal drug use; issues of violence and abuse,

including religious killings, abandonment and molestation; crime, in particular, murder, rape,

kidnapping, stealing, and arson. Other issues of concern were animal abuse, world population,

poverty, homelessness, health, and smoking.

Students identified performing and creating songs as ways musicians might describe and

critique such issues. As Natia writes, "Musicians could write music that told about what was

happening, and why it was wrong." Jessica describes how a musician might address the theme of global warming through a work that captures the sounds of polar bears harmed by a

threatened habitat:

For instance, if a musician wanted to stop global warming, s/he might write a

piece that sounded sad, and the sounds of animals in pain because of what was

happening to their habitat (like the polar bears, with their melting ice).

As the lesson concluded, Matthew and I invited students to begin to think about an issue they

would like to address in an original song or instrumental work.

Blowin' in the Wind

We listened to and analyzed the song Blowin' in the wind (Dylan, 1999, track 2). On copies of the song's lyrics, students underlined words, phrases, or lines that they found important. We pondered the questions the composer Dylan raises, for example, "How many times must the cannon balls fly before they're forever banned? How many years can some people exist before they're allowed to be free?" I invited students to think about what Dylan conveys in the lines "The answer, my friend, is blowin' in the wind." Robert responded, "It means that the answer is there, you just have to look for it." The words held similar meaning for Brendon and Camille. "It means that there's an answer out there, and you just have to find it," Camille observed. She underlined answer as an important word "because he is telling you to find the right way, the right answer. Keep on looking until you find the right answer." For Camille and others in the class, contemplating Dylan's lyrics can be the first step in "becoming more wide-awake to the world" (Greene, 1995, p. 4).

We later viewed a DVD of Peter, Paul, and Mary (2004) singing a cover version of Dylan's Blowin' in the wind (at the 1963 March on Washington) to discover how performance context may shape a song's meaning. We observed how songs become emblematic of social movements, such as the Civil Rights struggle; and how singers help to express and stir a country's social conscience. Performer Mary Travers described how singing Blowin' in the wind on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial during the Washington March awakened a sense of possibility for social transformation.

We started to sing, and I had an epiphany. Looking out at this quarter of a million people, I truly believed at that moment it was possible that human beings could join together to make a positive social change (Carry it on: A musical legacy, 2004).

The Poetry Lesson

Fieldnotes:

Along the tops of bookcases and ledge extending across the windowed wall of the Class 5B-302's sun-drenched classroom are bins labeled "C. S. Lewis and Narnia," "To Inspire You," "Roald Dahl," "Jerry Spinelli," among others. I flipped through the books in the "Social Justice" bin and found Girls: What's so bad about being good? (Mosatche & Lawner, 2001); Bad stuff in the news: A guide to handling the headlines (Gellman & Hartman, 2003); The Watsons go to Birmingham - 1963 (Curtis, 1998). I took a seat near the grey-carpeted meeting area where students gathered for their introductory poetry lesson. Joyce began by posing questions: "Have you tried to write poetry?" Numerous hands shot up in the air. "What is your experience? Do you know what it is? I want to know two things: What is poetry? What makes a poem or poetry?" Students' comments filled the large sheet of poster paper: "It can be rhyming words. It usually describes something. A person's thoughts and feelings. About absolutely anything." To the list, Joyce adds "It can "come easily" to the poet" and in swirling letters wrote the word Flows. "It's easier to write about your dreams," Brendon observed. Students brainstormed the variety of forms poems may take, for example, acrostic, concrete "shape," diamante, limerick, haiku, sonnet, rap.

When Joyce asked, "How do you think this introduction to poetry relates to music?", Natalia responded, "A song is kind of a poem with music in the background." Joyce nodded and, on the board in scripted letters wrote,

Poetry and Music Words are lyrics.

Underlining the relationship between poems and songs, she pointed out that one can convert poems to lyrics, and lyrics back to poems. "It goes together," Natalia observed. Joyce noted that a poem has a theme, a message or issue, and taking the theme "famine," swiftly composed the following acrostic:

Families

Are without food

Must feed the baby

I can't do it alone

No water

Emergency

Joyce questioned for whom one writes: "Is it just you getting it out? Or is it two-way? Do you care if you affect your audience? Does the painter think about what the viewer feels? Once you've produced that poem, think about who is on the receiving end." As the lesson concluded, she invited students to begin to think about a poem or lyrics that will go with the social issue they have chosen. Students returned to their desks, and in less than five minutes, Robert handed me a poem. "Joyce wanted me to show you this." "Did you just compose this entire poem?" I asked. Robert nodded. In What is happening to the world?, he describes a world where he breathes unhealthy air, as vehicles magnifying pollution line the street, and newspaper headlines report Iraq War casualties and spread of a "dangerous bug."

What is happening to this world?

I walk outside

take a breath of "fresh" air.

Wait, what is this?

Not air,

more like smoke!

I look at the street,

and I see

Hummers

Limousines

and SUVs

and as I watch

I think and think,

what is happening to this world?

I walk and walk

pass by a newsstand,

pick up the paper,

and read,

"500 more deaths in

Iraq. Dangerous bug is

spreading."

I put it down, and

and keep walking by.

And I think,

what is happening

to this world?

Pink

In music class we explored the political narrative of instrumental compositions, such as Pink from the album The land of nod (Washburne, 2006, track 1) and we discussed the album cover's image of the United States flag in faded hues of pink, off white, and blue. Students read an excerpt from an online radio interview, role-playing parts of the interviewer, Jason Crane and the interviewee, Latin jazz and salsa trombonist Chris Washburne. In the interview, Washburne relays how his weekly presence on stage with a microphone gives him an opportunity to convey messages through entertaining. He describes his turn toward composing more political songs and how he invites his audience to engage with those songs.

So I started to write songs that were in some way inspired by feelings stirred by the current political situation. And then what I would do is have brief introductions to them on the microphone, and cue people in who wanted to be cued in--people who were on the dance floor or were in a jazz club listening--that there's something behind what this tune is about, and that's the sentiment and message that we're trying to get across (Crane, 2006).

His compositions are a "wake-up call to those who are slumberous." He states that political action, through simply attending, can take multiple forms; and "just moving your body and dancing to the grooves that have this meaning behind them" can become an act of resistance.

Imagine

You may say that I'm a dreamer

But I'm not the only one

I hope someday you'll join us

And the world will be as one

-- John Lennon

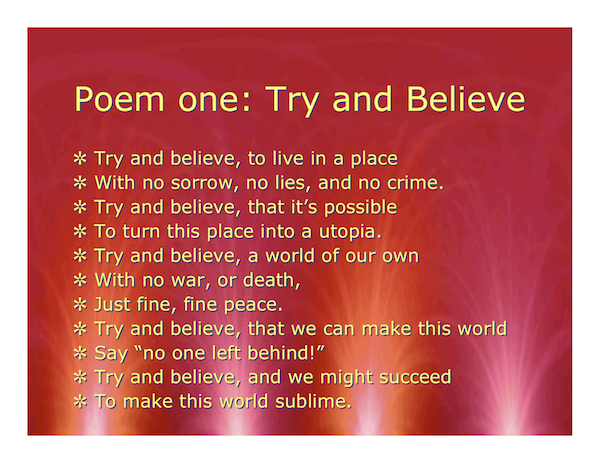

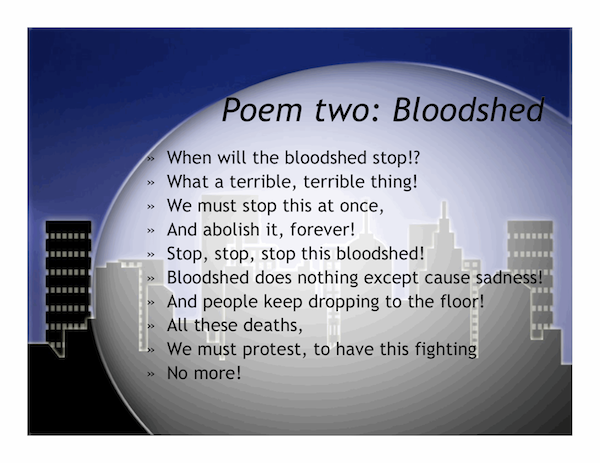

Unlike the previous musical examples we had listened to and analyzed, the song Imagine (Lennon, 2000, track 1) was familiar to most students. Many quietly sang along as the recording played. "What does John Lennon invite us to imagine, to dream about?" Michael, Matthew's student teacher, inquired. Students responded, "All the people living for today." "No countries." "Nothing to kill or die for." "All the people living life in peace." "What line or lines would you like to add to this song? What ideals, what kind of world would you like your audience to imagine?" Students' original words echoed Lennon's, evoking a resonance with his message of peace and a world without division. Themes of community, a world without violence and fear surfaced. Piper and Natalia invite us to "imagine there's no torture/No cries, no screams, no fears/Imagine people coming together/To laugh, to sing, and cheer." Rory, Robert, and Kurt conjure a world where "there's no bloodshed, no war, no anger, only peace." These 5th graders were naming their world, were imagining alternatives. Our hope, as teachers, is that this imagining might cultivate a sense of possibility and capacity to respond to others (Greene, 1995, p.38).

The investigation into how professional musicians explore important issues in our world through their music continued in the 5th grade classroom with repertory chosen by Joyce and by several students. Joyce introduced the song Peace on earth (U2, 2000, track 8), inviting students to reflect upon their emotional and physiological responses to lyrics and to analyze musical features of instrumentation, voice, and tempo. She invited students to compose their own alternative lyrics to fit the rhythm of the original songs.

Students also brought recordings to class to share with peers. Following the compositional process modeled in the music classroom, they suggested that these examples become springboards for original compositions. Their musical choices included Saul Williams' List of demands (2004, track 9); John Mayer's Waiting on the world to change (2006, track 1); and Wisin and Yandel's Oye Donde esta el amor? (2008, track 16), whose lyrics call out to listeners to "Hey, Pon de tu parte [Do your part]." These activities served to sustain and motivate the compositional process, in Joyce's words, "to keep them fired up and writing in between music classes." As I read Joyce's email, I noted the significance of this moment. The 5th graders were taking on the roles of initiators, of agents as they came together to discuss and create visions of a more humane future.

The Creative Process

The songs and instrumental pieces were composed and revised over the course of eight weeks. In an accompanying artist statement, students detailed the issue they addressed, why they perceived the issue to be important, and what musical decisions they made during the compositional process. In addition, students created album covers for a compilation CD of their compositions.

The Never-ending War

Recording of The Never-ending War

Calling themselves The Anti-War Penguins, Brendon, Kurt, Rory, Robert, and Simon, composed The Never-ending war as a response to war, in particular, the Iraq War.These musicians chose to compose an instrumental piece to accompany a slideshow of images of weapons and war. Kurt states, "I believe this is important because all the wars cause deaths everyday." Rory noted the environmental destruction war brings, "I think it is an important issue because...habitats are destroyed and after the war is over the area is a wasteland." Brendon and Robert also listed hate, poverty, and crime as products of war; and Robert added, "it's usually pointless."

The Never-ending War, scored for two guitars, conga drum, and accessory percussion, is, as Rory described it, "a rock type of song with guitars." Musical decisions included a loud dynamic level to capture the nature of war. Kurt writes, "We chose not to make it calm because it's war, and war isn't calm, but usually loud, with lots of different noises." Texture and the composition's length were also expressive choices. Robert states, "We also had the guitars come in first, then drums, then xylophone. We thought about making it five minutes long, one for each year we've been in Iraq, but the song was only one minute, forty-five seconds."

In a group interview, I asked members of the Anti-War Penguins to describe what they were attempting to convey in their piece. Rory began, "So we wanted to like focus on war and how it would sound...like certain beats of war, and how war can affect you." Referring to visual images in their composition, Brendon continued, "because in our classroom, we showed pictures of the atomic bomb and how much damage that can do." "Mushroom cloud!" Robert inserted. "And because it was The Never-ending war, we tried to make it as long as possible," Kurt explained. Robert added, "That's why there's three parts!" I expressed how I loved the way they ended their composition, with only the repeated sounds of the slit drum, and asked how that ending came about. "We used the slit drum like at the end to just keep going and going and going," Rory explained.

I questioned why they chose the particular guitar riffs and drum patterns they used. Rory responded,

Well, I made up the riff by like taking a Beatles' strum from the song Love, love me do, and then I took the song Boulevard of broken dreams. And then I took the chords, and I made this strum and mixed it with the chords, and it sounded really . . . Robert chimed in 'cool.'

Rory and Robert described how they played the chord pattern E minor, G major, D major, A major on guitars five times and then held down the strings to create a muffled sound. Kurt elaborated, "Well, we were thinking try something else instead of just repeating, like war, there's like different sounds, instead of just one sound, and so, yeah, there were different sounds."

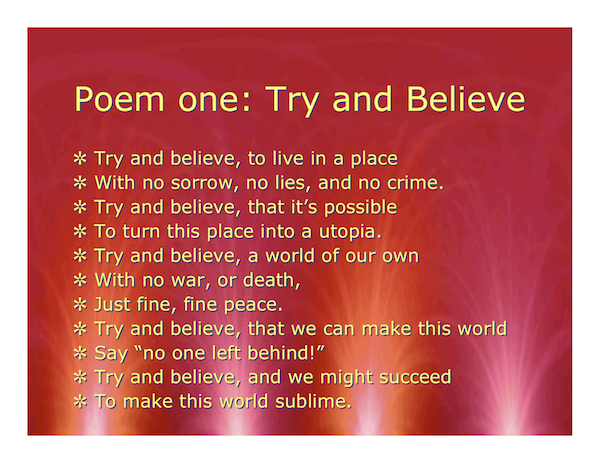

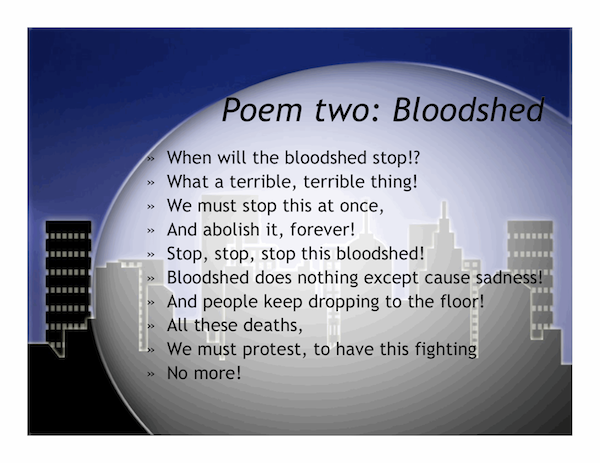

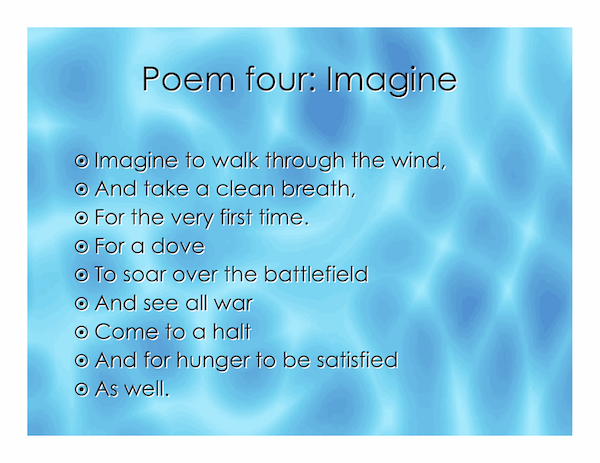

The final images of their slideshow featured three poems composed by the group's members:

How Would You Feel?

Recording of How Would You Feel

The song How would you feel, composed by Jessica and Julianne, addressed the issue of animal rights. The declining diversity of species and extinction of animals, such as the messenger dove, motivated Jessica's choice of theme. In her artist statement, she wrote,

I believed this was an important issue because I felt that people didn't quite understand how few animals are left. There used to be a type of dove called the messenger dove who were great in number. People killed them frequently without thinking and now the doves are extinct.

Julianne views animals and humans as entitled to the same rights and treatment. She stated, "Animals are like people. They should be treated correctly and nicely. They should have rights just like people have rights." The song How would you feel? invited listeners to briefly experience the world from the vantage point of an endangered animal.

How Would You Feel?

Verse

Out here in the city lights

Where no one knows the true meaning of night

And the only animals you see

Are the ones in the street

Or hanging from strings

Yes, these are the things

That tells you it is time

To stop and ask your mind

How would I feel?

If that was me up there

How would I feel?

If that was my home

They bulldozed

Chorus

If you had no rights

What would you do

Come let's be honest now,

No one likes the truth

Because they live in fear

Come on now

How would you really feel?

Verse

And how would I feel?

If it was my 'fur' they wanted

Because it is time to face the truth

How would you really feel?

If you lived in fear

Of everyone and everything

Fighting for your life

'Cause the simple truth is that

The animals have no rights

Yes,

They live in fear of life

Because of a shadow

With a silver gun

Oh,

How would you feel?

Chorus

Jessica described their decision to add lyrics to convey a message too difficult to express through instrumental sounds alone.

We made the choice to add lyrics because we weren't too sure how to express what we were trying to say through just wood instruments. We thought words would really get the message across. Animals have homes and feelings just as much as we do. We tried to make whoever was listening to the song...imagine him/herself as an endangered animal.

In discussing their choice to write lyrics, Julianne relayed their enjoyment in composing songs and poetry with Jessica's twin sister, and in this particular example, in communicating an important message and lesson to listeners, as follows:

Jessica, Julie, and I enjoy writing songs and poetry. It has been a group thing and habit of ours to write songs. We put in guitar and wrote lyrics that we thought people should hear. It taught them a lesson.

Dirty Old Dog

Recording of Dirty Old Dog

I repeatedly witnessed an ease and spontaneity in the compositional process. When "The AB (acronym for Animal Abuse) Girls" - Camille, Charissa, and Lilly - listened to The Never-ending war and How would you feel, they decided to abandon their percussion piece and composed Dirty Old Dog for guitar and vocals.

They took inspiration from their theme and dashed off the first verse and chorus with punctuating open-string guitar riffs in the hallway as I recorded another group's composition in the music room! As Lilly wrote, "We just thought about animal abuse and we got the words."

Dirty Old Dog

A dog left on the street

How could it be

The food he finds is ripe

Next to a dirty pipe

The love he needs to get

Is not a promised bet

The shaggy dirty fur

Is like a sturdy mop

Animal abuse is wrong

Thanks to you his life is gone

Let's stop it

All together right now!

Lilly described their decision to compose lyrics because of their significance, "because lyrics have a lot of meaning." Camille's choice of theme was charged with a sense of agency. She relayed, "I wanted to change that issue so badly in some way." Charissa described the helplessness of animals and expressed sadness over the lack of care they receive. Lilly regards animals and humans equally and asserted, "They are just like humans and nobody likes to be hurt like that."

Wake Up, Wake Up and In the Wild

Recording of Wake Up, Wake Up

The theme of animal rights inspired additional songs. Wake up, wake up, composed by Camille and Sophie, cautions the listener to awaken to the reality of animal abuse and neglect and take the right action.

Wake Up, Wake Up

Have you ever seen a dog or a cat

Have you ever fallen in love with your pet

And ever thought that he would be abused or neglected, so

Wake up, wake up to the reality of life

Wake up, wake up, don't believe that lie

Wake up, wake up, just do what's right.

When you see an animal walking down the street

With its ribs showing on all four sides

And you see blood on his ears, so

Wake up, wake up to reality of life

Wake up, wake up, don't believe that lie

Wake up, wake up, just do what's right.

For In the wild, Marla, Natalia, Piper, and Sophie created a jungle soundscape with interlocking rhythms played by a variety of drums, such as conga, slit, and bass drum. They selected instrumental timbres that, as Natalia wrote, "sound like animals," such as the spring drum to imitate a lion roaring and croaking frog guiro.

That's the Solution

Recording of That's the Solution

The impact of global warming on animals and their habitats stirred Sariah and Julianne to compose That's the solution. They chose to compose lyrics because they "send more of a message." Themes of conserving energy and reducing pollution intertwine, as they implored listeners to "help in their own special way" by turning off lights and mindfully disposing of trash. A synthesized keyboard beat accompanied the verse and chorus melodies and rapped coda section.

That's the Solution

Chorus

Turn off the lights

That's the solution

End global warming and

Stop all pollution

Turn off the lights

That's the solution

Verse

The air is as black as the dark night sky

You tell me it's ok but I know it's a lie

Everyone can help in their own special way

Together we can end the pollution today

Chorus

Verse

Don't throw pollution in a lake

Try your best do whatever it takes

Help us save the world and know we can do it all

Today or tomorrow someone will be sure to call

Chorus

Coda [Times 2; (this is a rap)]

Throw it away

Don't miss the trash can

I know you can do it

You can do whatever I can

Chorus [Times 2; (make up any ending!)]

Don't Take Drugs and Think

The dangerous reality of drug use is portrayed in the compositions Don't take drugs and Think. While the authors did not articulate what makes drug abuse a social issue they clearly had personal experience with this issue. In Don't take drugs, the composer Darryl warns the listener to not "be con," that "drugs will throw your life away." Darryl along with choristers Edon, Vaughn, Renato and Saranna rap the work, first without accompaniment, then again with a syncopated conga pattern.

Don't Take Drugs

Don't take drugs

Cause drugs ain't

The mode take my

Advice I got friends

That use mess up your

Brain and mess up your life

Pulling out guns and pulling

Out knife's so don't be con and

Don't be brought cause all you

Gonna do is get caught so take heed

To what I say drugs will throw your

Life away so what you gonna do so

What you gonna do stay away from drugs

And stay in school

Tariq conveys a similar message in his rap, Think, that features vocalized beat box rhythms. He instructs his audience to "think for you" and resist "just go[ing] with the flow."

THINK

Think of all the people Taking drugs and joking...

And there are other people trying to stop that smoking.

Think of all the people, Getting killed and jacked...

This is because people are taking drugs like crack.

Think for you; don't just go with the flow...

Do yourself a favor AND...

JUST SAY NO!!!!!!!!!!!

The Poetry Cafe

The vehicle of a poetry cafe was chosen to showcase the final products of our work together. Invitations were sent home, and on a hot June morning, parents and siblings of students in Class 5B-302 crowded into their classroom for the event. The carpeted meeting area, serving as stage, spilled over with microphones, a keyboard, and multiple percussion instruments. There was an air of solemnity and pride as students stepped to the microphone and, in their own words and melodies, spoke out against animal abuse, global warming, drug use, and war. When the performances were over and guests had departed, we raised our cupcakes into the air and toasted one another on the morning's success. The students, through composing and performing music, had reached toward Greene's vision of imagining a more just, humane community and world. "The role of imagination," writes Greene, "is not to resolve, not to point the way, not to improve. It is to awaken, to disclose the ordinarily unseen, unheard, and unexpected" (1995, p. 28). While the poetic imaginings of these young authors and activists could not resolve the grave social problems facing humankind today, they could disclose a sense of alternative possibilities.

Final Thoughts

Songs are like a conversation with a beat.

-- Natalia

Later that day, I invited students to reflect on our project, to think about all the music they had listened to, the songs, poetry, and instrumental pieces they had composed, and issues and themes they had explored. Is their experience of listening to or performing a musical piece inspired by a social issue different from simply having a conversation or debate about that issue? If so, how? How do they experience the process of composing music around a social issue? Do they perceive it as different from simply composing music?

Students identified commonalities between conversation and song. Lilly described performing a musical piece as "just like you are talking to someone." To Sophie, "It is the same thing but music has a tune." Conversations about social issues inspire Natalia to compose poems and songs that, at times, use the same language.

When I have a conversation about social issues I start to feel like writing so I write poems or song[s] about what I just talked about, sometimes using the same words. A conversation is not so different than lyrics. Songs are like a conversation with a beat.

Students acknowledged the expressive and affective potential of song. For Tariq, a conversation is "just talk[ing]." "When you sing you express yourself," he wrote. Charissa observed, "When you make music it means that you really feel it is important." For Marla, music conveys feelings in a way "that can be stronger than words." To Simon, "having a debate is wasting time because people just talk about it and don't do [any]thing. But in a song you get the message." Edon observed how making and performing the rap Don't take drugs "gave me a social issue that is important to me."

Students described the capacity of music to communicate a message more powerful than words. Robert stated, "When debating, you only have words to state your case. When writing music, you have sounds along with words to go with your argument. Sometimes sounds are more powerful than words." Julianne, too, recognized the affective and communicative power of musical sound.

Sound is more powerful than words. Music itself kind of has a message of its own. The tone of the music; major or minor. There are many different feelings in music. It is kind of different. A debate or conversation is one thing but a musical piece has something special of its own.

Students observed the potential of music to arouse a listener's empathy in ways that a debate cannot. Natia wrote, "I think that using a musical piece talks about the problem in a more gentle way, so that people care. If you're having a debate, you'll be arguing. You'll probably want to prove yourself right, so you won't try to help the issue." Voicing a similar view, Kurt noted, "When you listen to a song... you can actually imagine yourself in the middle of what the people are debating about." For Jessica, songs can move listeners, create lasting memories, and stir one to action. Conversations have a limited audience, while songs can be heard around the world. As she explained,

Debates are what people sometimes [call] a 'hot debate,' when people are arguing with each other. With songs and music it can sometimes bring tears to your eyes - which is a good reaction because it really sticks in your head later, and it makes [you] really want to do something. Also a conversation usually doesn't reach the ears of [more than] 2 - 3 people, while songs could win awards and be played all over the world.

Evidence of students striving toward the Freirian ideal of being more emerged as they described how playing and composing music around a social issue evoked feelings and conveyed their commitment to an issue. In comparing composing music around a social issue to simply composing music, Jessica observes

I would have put the same amount of effort and work into it, but it wouldn't have been as straight from my heart as the animal rights issue. I truly want to help the animals, and I think everyone else should try to too.

Jessica's medium for such advocacy and agency became songwriting. For Natia, performing the song Wake up, wake up stirred "different" feelings. Absent from classes during the compositional phase of the project, she wrote, "I haven't composed music before, and I didn't compose this one. But performing this song felt different than singing a song by my favorite artist, or whatever. It felt really good." In contrast, Robert views the processes as similar, both motivated by an idea. He observed, "I don't think there is a difference in addressing a social issue or simply composing music because when writing music, you don't just write, there has to be something to address, or else there's no motivation for the song."

Coda

I carefully secured the top flaps of the cardboard box with transparent packing tape and attached the mailing label addressed to Class 5B-302. Tucked inside the box were twenty-eight CDs, compilations of songs, instrumental pieces, and album art created during our eight-week project.

My letter to Joyce and her students applauded the creativity I witnessed in our brief sessions together. Words, rhythms, and melodies - manifestations of thoughts and beliefs about issues in the world - had seemed to pour from them.

Our investigation challenged us to find meaning in Dylan's lyrics Blowin' in the wind and to imagine, with John Lennon, a more humane, peaceful world; to learn how performer Chris Washburne "cues in" his audience to political messages of instrumental works, such as Pink; and to reflect upon our affective and physiological responses to U2's Peace on Earth. Students named and confronted world issues they believe to matter most. Their words and lyrics reveal a reverence for animals, endangered and neglected; indignation aroused by casualties and destruction of war; a sense of agency toward problems of global warming and pollution, and a chilling awareness of the effects of drug abuse. Their understandings of music and song as vehicles for expressing their stance and feelings toward world issues were honest and deeply felt. In coming to know and express their concerns about the world, they were, as Freire would identify, in the process of being more; and being more suggests a "consciousness of possibility" (Greene, 2001, p. 47). To be conscious, writes Greene, is to reach "toward a fullness and a completeness that can never be attained" (1995, p. 26).

Von Donnersmarck's cinematic example, which opens this study, underscores music's sheer power to touch within its listeners at the deepest, most profound level, a consciousness, a sense of possibility, of living one's life as something more. In an interview with Charlie Rose (2007), director Von Donnersmarck relayed the challenge he presented to the film's composer Gabriel Yared for this scene:

I said to him, I want you to write a piece of music, which if you could travel back to 1933 and spend one and a half minutes with Hitler, and Hitler hadn't yet committed any of his atrocities and you would not be allowed to speak to him. You would not be allowed to kill him. You could only play him a new piece of music, what would you write?'

We, as musicians and educators, recognize the inherent force of music; yet we observe how music pedagogy and curricula are so often stripped to conceptual frameworks of elements, styles, and skills. Our education practice cannot continue to be, as Freire writes, "untouched by the issue of values, therefore of ethics, by the issue of dreams and utopia, in other words, of political choices, by the issue of knowledge and beautifulness, that is, of gnosiology and aesthetics" (2004, p. 89).

An urgency prompts us as music educators to consider a new paradigm, one that embraces social justice and centers its concerns within our pedagogy and curricula. Artists who courageously voice their anger and dreams for our world can inspire our students and us. Their voices may resonate with, and, in turn, ignite the social imagination of our students, as they did for Class 5B-302.

Notes

1. Names of student participants were changed in order to protect their identity. Permission was granted to use the real names of the teachers and school.

References

Apple, M. (2000). Official knowledge: Democratic education in a conservative age. New York, London: Routledge.

Baxter, M. (2007). Global music making a difference: Themes of exploration, action, and justice. Music Education Research, 9(2), pp. 267-279.

Crane, J. (2006, October 23). Chris Washburne: Instrumental activist. All About Jazz. Retrieved from http://www.allaboutjazz.com/php/article.php?id=23285

Curtis, C. (1998). The Watsons go to Birmingham - 1963. New York: Scholastic.

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Continuum.

Freire, P. (1996). Letters to Cristina: Reflections on my life and work. New York and London: Routledge.

Freire, P. (2004). Pedagogy of indignation. Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishers.

Freire, P. (2007). Daring to dream: Toward pedagogy of the unfinished. Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishers.

Gellman, M. and Hartman, T. (2003). Bad stuff in the news: A guide to handling the headlines. San Francisco, CA: Seastar Books.

Giroux, H. and Shannon, P. (Eds.) (1997). Education and cultural studies: Toward a performative practice. New York, London: Routledge.

Greene, M. (1995). Releasing the imagination: Essays on education, the arts, and social change. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Greene, M. (2001). Variations on a blue guitar: The Lincoln Center Institute's lectures on aesthetic education. New York and London: Teachers College Press.

Mosatche, H., & Lawner, E. (2001). Girls: What's so bad about being good? New York: Three Rivers Press.

Rose, C. (2007, May 18). Conversation with film director Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck. The Charlie Rose Show. Retrieved from http://www.charlierose.com/shows/2007/05/18/1/a-conversation-about-film

Telonidis, T. (2007, September 16). Immigrant songs offer new twist on old sounds. National Public Radio. Retrieved from http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=14415291

Von Donnersmarck, F. (2007). The lives of others [DVD]. New York: Sony Pictures.

Musical Examples

Dylan, B. (1999). Blowin' in the wind. On Bob Dylan's greatest hits [CD]. New York: Sony.

Lennon, J. (2000). Imagine. On Imagine [CD]. New York: Capitol.

Mayer, J. (2006). Waiting on the world to change. On Continuum [Music download].Chicago: Aware Records. Retrieved from iTunes.

Peter, Paul, and Mary. (2004). Blowin' in the wind. On Carry it on: A musical legacy [DVD].Burbank, CA: Rhino Home Video.

U2. (2000). Peace on earth. On All that you can't leave behind [CD]. London: Polygram UK.

Washburne, C. (2003). Guantanamo. New York: Wash and Burne Music.

Chris Washburne and the SYOTOS Band. (2006). Guantanamo. On Land of Nod [CD]. NewYork: Jazzheads.

Chris Washburne and the SYOTOS Band. (2006). Pink. On Land of Nod [CD]. New York: Jazzheads.

Williams, S. (2004). List of Demands. On Saul Williams Live at Double Door [Music download]. Retrieved from iTunes.

Wisin and Yandel. (2008). Oye donde esta el amor? On Los Extraterrestres - Otra Dimension [Music download]. Puerto Rico: Machete Music. Retrieved from iTunes.

Wyse, P. (1998). Sonata, Appassionata, Opus 57, by Ludwig von Beethoven. Recorded in Griswold Hall, The Peabody Conservatory.

About the Author

Marsha currently teaches at State University of New York at Potsdam, where she directs the Crane Latin Ensemble Norte Tropical. As part of her dissertation fieldwork at Teachers College, Columbia University, Marsha studied the zaponas [panpipes] with an Ecuadorian master musician and subway performer; the dizi with a former professor of the Beijing Conservatory; and the cedar flute with a Native American storyteller and musician. She has also studied pre-Columbian music with a Huichol Indian in Guadalajara, Mexico. Marsha is the 2010 recipient of the prestigious SUNY President's Award for Excellence in Research and/or Teaching Relating to Cultural Diversity. Marsha teaches Comprehensive Musicianship at Teachers College each summer.

|