International Journal of Education & the ArtsEditors

Margaret Macintyre Latta

Christine Marmé Thompson

| |

http://www.ijea.org/ |

ISSN 1529-8094 |

Volume 12 Number 14 |

October 31, 2011 |

Free Improvisation; Life ExpressionNg Hoon HongNational Institute of Education, Singapore

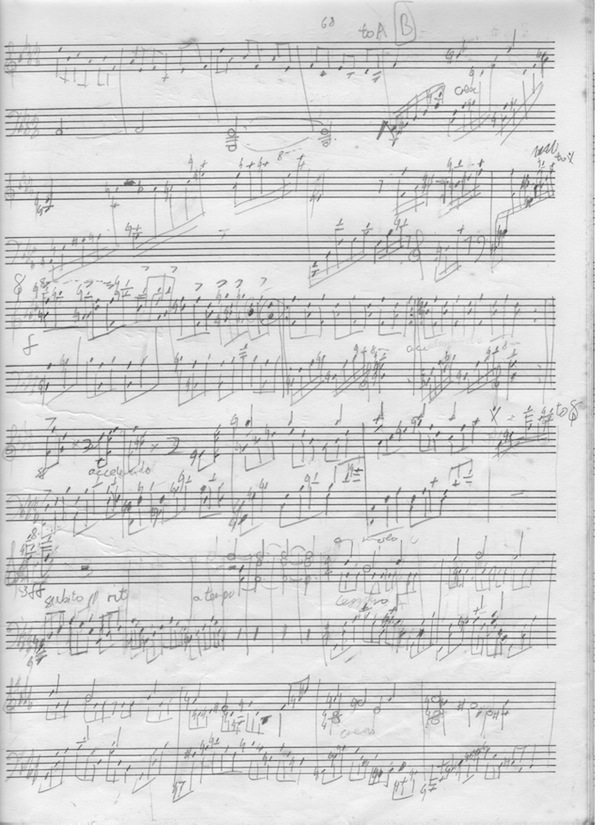

Citation: Ng, H. H. (2011). Free improvisation; Life expression. International Journal of Education & the Arts, 12(14). Retrieved [date] from http://www.ijea.org/v12n14/.Abstract This autoethnographic study seeks the value, position and possibilities of free improvisation in the musical field. It explores how embodied knowledge, dialectical exchanges, emotional and intellectual stimulation constructs and reconstructs experiences in various contexts for the free improviser, who is both researcher and actual piano performer. This is done by experiencing and reflecting on the connections and interactions between different aspects and events in free improvisation, seen here as a phenomenon for varied, multiple processes individualized by one's adopted style, culture and character. The research suggests a shift towards a more holistic and integral paradigm for experiencing and understanding music through free improvisation as a process in life. Visual Abstract  I was at the piano again one day. He was a young boy who wanted to weave a fantasy world with sounds from his brown piano in the living room. He would return frequently to the piano every day to plough through all available scores. It was fun and pleasing. That was all. He progressed fast, completing Grade 8 in performance by 14 in less than 5 years. Thinking he was a gem, his mother got him two cheap classical piano music tapes. He placed them in the player, got riveted by new sound possibilities, and began to deviate from the score and explore. Wanting to create fantasy soundscapes, he asked, "Can I learn to write music?" Baffled faces stared back. Playing by the score remained the only way he knew. He notated his first piano piece, at age 12. At that time, his parents often argued when together. And then his father contracted cancer, got involved in a fraud case and filed for bankruptcy. All these, he didn't wish to understand. He was powerless. He went to a competitive school, where stakes overbalanced the space to listen to himself. He learnt discipline and perseverance, which became tools to practise less. Music then became a transcendental product - a portable showcase with a life removed from his immediate needs and dire situation. He wished he could play for the pure pleasure of it, as a counterpoint to his life. He discovered power when cocooned in his music - through composition, anesthetized by sounds from which he created an alternate world, in which he was God. His financial situation did not stop him from composing on his own. Drawing upon his Western Classical knowledge, he wrote on book after manuscript book, pencil marks smudged from frequent rubbing, tinkering at the piano, keys clogged with rubber leavings, to obtain sounds he wanted (Figure 1).

By then, he knew he could never become one of those great pianists he heard on countless CDs. He also knew that these countless pianists had recorded countless interpretations of the same old music. And he wanted his own world.

It was many years later. He returned home from work, tired and depressed. After pursuing Architecture, he turned to education for a lack of direction. It wasn't the job he really wanted, but he had learnt acceptance. A sense of repression shrouded his being. He saw his piano, stoic and silent in the corner, and approached it. In his mind, his world re-emerged. He began to fiddle, too tired to set his inspirations on paper, and played on. Complexities from his classical grounding did not come across, but he was at ease with the fluidity of the sounds. Whether they were cliche or extraordinary no longer mattered. He began to reflect himself through sounds, neither challenging nor conforming, but simply be. His technique and language grew more complex; his thoughts and emotions flowed increasingly freely with the ebb and flow of the sounds. He became alive (Figure 2).

Settling into my usual rational self, I penned down questions prompted by this recollection of my past: Can there be a use for music within one's personal space and time? Can musicians without the ability or chance to do music professionally discover their own musical expression? Can free improvisation substitute notated music for them to partake in musical expression, given the fast-paced, consumerist society and the majority population with limited musical training? Can free-improvisation as a practice, by satisfying and reflecting the needs and desires of the performer, be an act of consumerism in itself, making it more in line with the present society? I sought to first understand what free improvisation is, and is not. It is neither an offshoot to music creation, a subset of conventional compositional technique nor groundwork to rigidify into written composition. It is also not an un-notated score, system or style already established in the mind, like Jazz, Indian improvisations or African musical performances (Blum, 1998, p. 40). Despite these, free improvisation is not freed from the influences of idiomatic norm, cultures and styles. It is a diverse collage of idioms and styles crafted using whatever tools, skills, and experiences the improviser may have, changing styles and techniques as he feels the need. It emphasizes on the evaluation of what has happened and how to proceed next, and the behavior of all parties (audience and musicians) involved. It is "without preparation and without consideration, a completely ad-hoc activity, frivolous and inconsequential, lacking in design or method," even though "there is no musical activity which requires greater skill and devotion, preparation, training and commitment" (Bailey, 1992, xii). The Free Improviser is therefore one who lives through the experience of music making in various contexts, responding to himself and his surroundings in a constant dialogue, the architect who uses stylistic idioms and techniques which he may deploy or discard as he will, and not as prerequisites for music-making. Free improvisation seems so fundamental to music, and yet never mentioned in my entire Western Classical training. I find this appalling. I was taught to understand the music score, but not in relation to myself? Subsuming in dead men's works was not what I wanted, and explaining that I could reinvent the old was not enough. Free improvisation is a neglected art that needs to be addressed (Nettl, 1998). This prompted me to begin my journey as a performer and student of free improvisation for this research.

Burnard (2007) gave the first inkling of what suited the path of my research: by studying improvisation as a phenomenon through the themes of lived time, lived space, lived body and lived relations. Using autoethnography seems a good approach to study free improvisation, since music is embedded in culture (Hall, 1992), and complements existing research approaches to improvisation, including understanding the system behind the process (e.g. Pressing, 1984, 1988), studying it as a social phenomenon (e.g. Burrows, 2004) and as personal practices of the Other (e.g. Sansom, 2007). Ellis (2004) describes how one uses narrative to organise experiences into temporal, meaningful episodes, thereby denying the one truth, or approach to why we live as we do. Free improvisation as an experiential process coincides with the autoethnographic reconstruction of embodied experiences situated in complex interactions between the cognitive, bodily, emotional and spiritual. Rather than seeing autoethnography as "retreating into personal inner subjectivity, it can instead establish and stabilize intersubjectivity" (Roth, 2005, p. 15). The purpose is not to create objective observer-independent knowledge, but to bring about a maximum of intersubjectivity by understanding the Self to understand the Other. I used autobiographical performances as a means to understand the connections and interactions between and within the 'I', my improvisation, and beyond the 'I', similar to performance ethnography, where performance complements fieldwork to express that which cannot be expressed in texts, as well as reflect on how performance can supplement and critique these texts (Conquergood, 1991). Much like the phenomenological nature of musical experiences, the ethnographic experience in improvising is built around encounter (Porcello, 1998). I hope to shift my journey towards a more holistic and integral paradigm for critiquing and experiencing music - by situating the Self within the experience and engaging it in a situated, evolving and revelatory narrative. I began my research by performing and recording my performances in various contexts. Performances on my digital piano were audio-recorded and computer-notated using Reason 4 (music arrangement software) via USB connection to my computer. Immediately after, notes were made on the processes, my comments being guided by the existing literature. After this, the audio recordings of the improvisations were replayed, and a second round of notes was annotated on the note maps generated by Reason 4 at specific junctures where my recollection was triggered, to engage in a reflexive dialogue with the music based on the re-evoked experiences. For performances not on the digital piano, observations were made solely from the replay of audio-recorded performances. This is an adaptation of Interpersonal Process Recall (IPR), a method adapted by Sansom in his study on identity within the improvisational practice (Sansom, 2007). In addition, I also wrote observations as reflexive accounts before and after performances that were more narrative, autobiographic and contextualised. I worked inductively from the data gathered to present findings in traditional categories by first writing summary phrases on significant points, and then letting themes emerge. The themes were later organized into categories, and considered in relation to each other to explore their associations and interactions. Finally, master themes were established, under which related emergent themes were connected together. To write the final narrative, I listened to the recordings again while reading the transcripts, and reorganised them under master themes. I tried to stay close to the words and their meanings, editing for clarity and flow. I also quoted and if necessary edited extracts to illustrate my points, and overlay the narratives with more traditional analysis and literature reviews to achieve greater clarity and depth of discussion. A total of 20 improvisations were performed, recorded and studied between August 2009 and February 2010 using a variety of pianos including Nordstage 88 stage piano, Shigeru Kawai SK3, Clavinova CVP-301 and Yamaha C3. To address the research questions which are rooted in the current value and position of free improvisation, I sought to understand it first by rationalizing the process, and by living it.

Preconceptions and Errors I first looked at the systematic musicological aspect in improvisation, focusing on the concept of free improvisation as something that can be analyzed systematically, independent of specific cultural contexts (Nettl, 1998, p. 2).

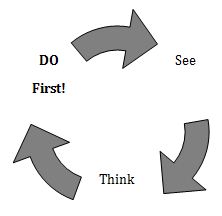

My first improvisational entries bring to mind a method of connecting between my sensibilities and creation in an architectural module I attended in university more than a decade ago. We had to train our minds not to plan first, but to always react to what was done with the materials in our hands while engaged in the moment, evolving our thoughts with the product in a Do-see-think loop (Figure 3). Though this process is a loop, the process must always begin with 'Do', as opposed to the convention of thinking and planning first. As a result, our building models were fantastical structures that were striking architectural statements. The making sense of it all came after. This model bears similarities to a model by Pressing (1988), who notes that all existing theories in improvisation begin with a three-stage information-processing model, consisting of sensory input, cognitive processing and motor output, which translates to hear, think and play. Using the Do-see-think loop, the sequence will be rearranged as play-hear-think, a practice I prefer to allow greater freedom of expression and moment-to-moment engagement. This resonates with my experience of limiting preconceived notions that stunt the natural creative flow in free improvisation. I wonder if I can improvise a piece using primarily repeated notes, and how long I can sustain the pattern before I need to break out of the constraint? In Pressing's (1988) model are feedback loops which allow for error correction and adaptation, so that the discrepancy between intention and actual motor and musical output is narrowed. I tend not to view my performances as erroneous and in a constant need for correction to a rigid intention. Rather, with each sound given voice in space and time, it becomes valid by its very existence, and a development to the next sound. ...errors in playing were not seen as failures or errors, but as stepping-stones to build upon to attain the sounds desired, or when accidental expressions that deviated from my intentions that were delightful became a feature of my playing.This is closely associated with play and experimentation, discovering through 'accidents', which Hall (1992) exerts is serious business and a means of mastering skills. Improvisation, while playful and experimental, also integrates the development of analytical listening and performance skills. In free improvisation, the urge to discover unique experiences is done with less fear of failure due to its evolutionary nature, as errors become a source for experimentation in an ever-changing landscape, where there are no errors. Imagine what this mindset can mean for budding artistes! Layers of Consciousness As we 'Do First', where do we get the notions to begin? What instincts do we follow? Since we think as we live, it is only a question of whether the thinking and subsequent actions is a conscious effort or relegated to the subconscious, automated level. This basic understanding is evidenced in my improvisations, where referent to an acquired knowledge-base and selection based on culturally-influenced personal preferences determined my playing style and technique. My theoretical learning, stylistic notions and technical practices from the past were relegated to my subconscious, and were executed at an automated, instinctive level based on my imperfect memory, be it short or long-term. I warmed up on my Shigeru Kawai grand by playing introductory passages from Rachmaninov's Piano Concerto No. 3 and Bach's Prelude and Fugue in C# Major, in anticipation of doing something lighter and faster. Images of passages based on what I had experimented during the warm-up flashed through my mind. ...wanted a static and bound feel, and played 3 sequences of 4 chords...Active, conscious decision-making and execution juxtaposes with subconscious automated action in my improvisational process, my layers of consciousness weaving in and out, as I move between active decisions and automated action. Compared to performances of scored music, I experienced more instances where I relinquished conscious control to the automated. Conscious thoughts are often associated with active decisions that significantly affect the macro direction and flow of my improvisation, whereas subconscious thoughts are related to ingrained habits resulting from past influences, experiences and training that generate the micro details of my improvisation, which suggests the necessity of a certain technical familiarity and musical knowledge base that is culturally and stylistically informed (Pressing, 1998). These automated actions may be derived from short-term or long-term musical referents. This brings to mind Mvromatis's probabilistic computer model of chant improvisation in Greek Orthodox church style (Temperley, 2007), which consists of a network of nodes which represents states, connected by transitions between them. When the machine goes through a state, it produces a sound output. To connect to another state, the machine must go through one of the possible transitions which also produce sound outputs, the choices being probability-based and constrained by stylistic notions input into the machine. This idea of nodes where decisions are made, with less-determinate forms in between, is similar to Pressing's idea of time points, where decisions are made about the subsequent actions to be triggered (Pressing, 1988). These key points are not unlike conscious decision points in my improvisation, and the transitions between points resonate with my subconscious, automated playing drawn from past referents. If one's theoretical learning, stylistic notions and technical practices provide the foundation for the automated aspect of one's free improvisation, can limited exposure and training prevent a person from free improvisation? For this, I return to Bailey (1992) who states that free improvisation is "open to use by almost anyone -- beginners, children and non-musicians. The skill and intellect required is whatever is available. It can be an activity of enormous complexity and sophistication, or the simplest and most direct expression: a lifetime's study and work or a casual dilettante activity. It can appeal to and serve the musical purposes of all kinds of people..." (p. 83-84). Structuring Sounds in Real Time Interesting to note how the music is organized intuitively with two major sections A and B. Within each section are minor sections, e.g. the 3 cycles in section A, and within each minor section are small segments e.g. the sequence of 4 chords in a cycle. This suggests inherent organization of the mind that jigsaws whatever motifs and structures that are prepared, or appear when improvising, be they macro or micro, and negotiate them into a coherent whole by making complex hierarchical and heterarchical mental associations.How do my improvisations develop and change over time? I listened to recorded replays of my improvisations and wrote down observations which were later categorised and grouped according to common themes. From there I listed down changes evidenced in my performances, as I understand them.

Structure and organization - macro sections

Structure and organization - micro organization (within macro sections)

Each macro section is defined by broad distinct musical features and intentions as I perceived them through playing and recalling my cognitive processes through playback. Micro organizations exist within the macro sections to develop these sections. Of great import is how I strove to evolve sounds over time, guided by micro and macro frame(s). The macro frame, which is formed by conscious decisions, constructs a web of multilevel constraints that serve as guiding principles for the whole piece, though it in itself may evolve in the course of the performance. Micro frames in the form of organization and patterns on the other hand shape the various events within the macro sections during the performance that seem to be triggered at decisive time points.

It brings to mind a reductionist model on the process of solo improvisation by Pressing (1988) consisting of a sequence of musical sections, where within each are musical events called event clusters. In each event cluster are various components that affect the decisions made within. Each component is divided into 'intended', specified at specific time points, and 'actual', which is perceived from sensory feedback. The gap is narrowed between the 'intended' and 'actual' based on subsequent sensory feedback that inform the components of future decisions and actions. Only the schemata for action are triggered at the time points; the exact motor detail is fine-tuned based on feedback processes that occur after each time point. Overlaying the whole decision-making is a general referent to guide the improviser to generate the general behavior during the improvisation. In effect, this referent becomes a template as a basis for the improvisation which one conforms to and breaks away from in performance (Cook, 1990).

My own observations of my improvisations conform, at several levels, to von Emmel's description (2005) on learning to improvise: 1) Connecting with the environment and Self; 2) Staying with a concrete perception and tracking its path (intention); 3) Frame - system or boundary that guides or governs a segment of the music; 4) Evolving - the accumulation and development of minor (micro) frames to form a meta (macro) frame, and 5) Context of the performance. I like how Ruth Zaporah uses the terms 'shift', 'transform' and 'develop' to describe the technical approaches to change - ubiquitous and a constant in life, relevant in improvisation since the act of improvising is a reflection and a semblance of the mechanisms of life (von Emmel, 2005).

Summary

In this landscape of change over different levels of consciousness, there is the past that is backward-looking - my theoretical learning, stylistic notions and technical practices that form the basis of my training and preconceptions that result in error perception, and the future that is forward-looking, challenging and evolving my past, where errors become stepping stones. These are two forces in constant tension, but lose meaning and definition in the absence of the other. To understand free improvisation is to understand the essentiality of this forward-looking aspect, which is elevated to a position of prominence in the moment-to-moment involvement. This aspect may be relatively neglected in other musical practices but is driven to the forefront by the nature of free improvisation, and it is in this forward-moving musical procession, based on a past, that its significance can be found.

Encounters with Myself

The following are extracts from my improvisations alone, selected to show strong connections to my changing life states. Often they were performed when there was a need to express that which cannot be articulated through words as a more immediate link to one's being. They are strategic, intentional, deeply felt forms of performed individual and social activity, and living embodiments of how multiple levels of consciousness and activity synthesize to enact ontological meaning within sounds, within the flow of internal and external time.

I struck the first chord in D major for its tonal, open sound, the way I wished my

improvisation to be. My right hand began its cantabile singing over chords - as I tried to

immerse myself. My hands seemed to move on their own volition, guided by my connectedness

to my thoughts, emotions, body, my instrument, my environment. Motivated by my ability to

construct my personal sounds and the satisfaction derived, I freed my accompaniment into

free form broken chords, so that in its contrasting freedom from the introductory section, I

could sing more deeply from the Self. I used the subdominant position frequently in the

progressions and cadences to achieve the sense of peace and resolution.

My emotions rose - emotionally expanding and reaching out, and the sounds rose in

response. My emotions ebbed, and the sounds receded. I ended in D major, a conforming

move for a peaceful, non-confrontational beginning.

Throughout, it felt like I was emotionally tearing, perhaps because it felt like such a real

reflection of myself, like a sort of self-recognition. Already, I view this string of

improvisations as a journey to accompany my life.

From Improvisation 1

I began with a simple scale-like melody and common chord accompaniment, and the sense of

conformity gave me a sense of well-being. Then I moved on to elaborate with arpeggio-like

accompaniment to create more movement, while maintaining the easy-listening style. With my

right hand, I sang in cantabile style on the keyboard, sounds lifting and falling with my

feelings. Then I plunged into a faster, contrasting section of automated, ostinato bass

patterns, feeling more alive as I played. I shortened musical phrases whimsically, as if I was

talking with my fingers, much like switching to a new sentence in midsentence as a new

thought came along. With the return of the scale-like melodic pattern, I transited back to

calmness and ended the way I began, soaked in a calm, comfortable world.

From Improvisation 4

I began with a slow, dissonant, four-chord motif repeated in sequence for a static, bound feel.

The tempo was slow; I spent time listening, feeling and looking at keys I felt best represent my

feelings. Within the constricting monotony, I struck the first high chords to demonstrate my

frustration and urge to break out of the tedious system. My emotions surged with frustration

and my music accelerated. In the grasp of my feelings, my subconscious took over and I

smudged the moving bass sounds with heavy pedaling. This mess of sounds fed my confused

emotions, so I created more of it to satiate, reinforce and encourage my feelings. I fought to

strike high chords into the mass of bass confusion, pitting my mental insistence against the

limitations of my technique. I reinstated the chord sequences from the beginning at twice the

original speed, building up in intensity and reintroducing the high-chord motif.

The constriction left me, at least momentarily.

From Improvisation 5

I stared into space as I began, letting my fingers run with their conditioning and training,

adapting to and interacting with the keyboard. Tonal sounds from Tian Hei Hei crawled into

the introduction as I gravitated towards it to establish my comfort zone. I kept my emotions at

bay, and moved with detached thoughts, like a bystander, relying primarily on subconscious

automated actions and reactions to feedback, and the whims of passing thoughts.

I rambled, shifting gradually into less tonal realms. Suddenly, I felt the urge to create a great

change, and turned the meandering melodies into loud, abrupt, detached chords. I wanted to

do that simply to exert my freedom. It felt important to demonstrate that change at that

moment, to show that I could, and to do it. I flowed on from these rough-edged passages to

gentler passages of descending scales, reflecting fluctuations of my mood.

I rambled on, and built up to a climax of mainly automated actions to indulge my emotions.

The sounds ended abruptly. I spaced out a while more, and then turned off the stage piano.

From Improvisation 9

I struck the first few notes, and they drove me on with unexpected force. The depth of the

keys' touch produced colorful shades of sounds that blended in pleasant, unexpected ways.

I began with a singsong melody on Alberti bass with impressionistic overtones. Wanting to

humour an imaginary audience, I interrupted this with a sudden twist - a fast, abrupt motif. I

went on with a musical recitative, to communicate in my language. This monologue I soon

broke with staccato motifs, and moved into a catchy ostinato bass pattern, which formed the

datum around which other sounds were arranged. In the spirit of fun, I struck a loud bass

octave, and it became a musical juncture. Then I broke away briefly from the ostinato for a

needed respite, before moving on in perpetual motion, building momentum as my excitement

grew. Tension mounting, I accelerated within the boundaries of the ostinato and distorted the

metric system. Pent-up by the long buildup and challenging the boundaries further, I struck

random note clusters in descending order for sharp clashing sounds.

Finally I overcame the ostinato cage and broke into controlled chaos, letting my fingers dash

across the keys in automated fashion to satisfy my adrenaline rush. Propelled by this musical

climax, I struck a rapid motif in the high register. Liking the sound and the quick, random yet

consistent automated motions of my fingers, I repeated it for emphasis, and directed its

controlled randomness toward the climatic end.

From Improvisation 10

In the process of improvising, complex relational dynamics emerged as conscious thoughts - articulated sounds, actions, emotions and thoughts in the performances connected with each other and various other aspects of the performance as I lived within as well as apart from the event.

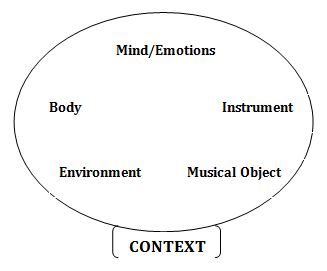

I noted how freely improvised music emerges from the inter-relational dynamics of various aspects that are of significance to the process:

The interactions of these aspects and their dialectical arguments demonstrate how, in living the free improvisational process, dynamics within and between these continua negotiate as I shift between planes of consciousness that are layered over the same timeline. From a lived experience, these aspects of involvement and others connect and correspond in a complex manner, which govern the selection and re-selection of events as well as guide the overall pacing of the piece (Bailey, 1992). This creates perpetual tensions in their complex interactions arising from the priorities and limitations of their individual governing systems, in the process creating the resulting definition to the improvised music. These aspects of involvement are influenced by and congruent with Sansom's six categories of involvement evident in free improvisation in a group setup (Sansom, 2007), which includes a sixth category on the involvement of the partner.

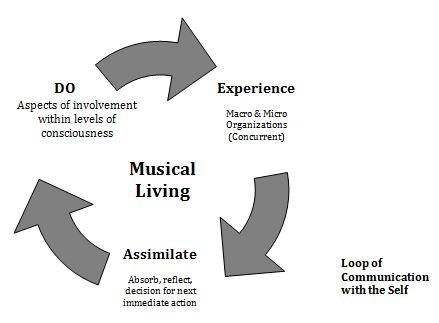

In these experiences, I have inevitably created Situated Music; I have returned music back to a form of daily social interaction with the inner self, a daily cathartic ritual. I have created a Musical Diary, in which each piece of free improvisation is initiated by its Context. With that, I constructed a circle enveloping the five aspects of involvement and labeled it 'Context' (Figure 4).

In this setup where music is situated, the context becomes the overall driving force, where individual analytic interpretive processes are necessary in developing improvisational skills appropriate to the performance context. Such skills might consist of knowing appropriate and inappropriate performance techniques for a given context, and of acquiring the ability to recognize, distinguish, and deploy the musical possibilities organized in cognitively coded musical patterns acquired through personal exposure and experience (Porcello, 1998).

Contextualized free improvisation promotes the structuring of musical thoughts into one more embedded in daily life rather than one contrived, formalized and indoctrinated. They are emotional, introspective, mundane, virtuosic, intellectual, gruesome, all expressions of the expressive and constructed 'I' of the moment, in transit from the past to the future.

Hence, it is a musical diary for self-indulgence, self-release, self-growth, balancing external realities through inner realities, and mediating life through sounds.

Encounters with Others

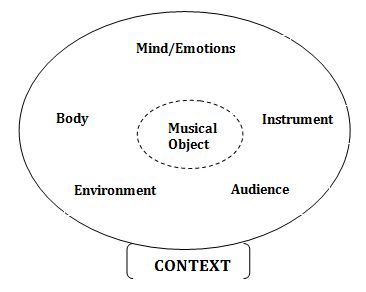

Looking at the five aspects again, I put in a sixth category - Audience. Having reached a level of fluency with free improvisation, I felt the urge to reach out to others. I wanted to know what others thought of my improvisation, to find more purposes for it, and to achieve recognition.

'What happened?' I asked, sensing his mood, and surreptitiously trying to gauge the angle I

should take with my improvisation later.

'I had to work in the morning. Went to the temple with my family in the afternoon. When I was

about to come at four, my mum wanted me to drive her around on her errands. Came straight

after,' he grumbled.

The last I checked, it was Sunday. No wonder.

'Well, can you listen to my improvisation? It's for my research,' I said with false energy,

putting on my teaching voice to attempt control of the situation.

'Just listen right?' he asked, then plopped himself down on a chair next to me at my grand, a

jaded look on his face, then heaved an exaggerated sigh, which I ignored.

'So what kind of music would you like to hear?'

'Anything.'

Trying to stay unfazed, I said, 'How about you give me three notes within the reach of a

hand.'

'Any notes?' he asked, as if needing instructions for the monumental task of random

choosing. He reached out.

F# G# A#

So conservative and systematic, I thought. How can I work with that to suit his tastes and

present state of mind within the scope of my acquired and preferred musical language?

Thinking back to his praise of a soothing, atmospheric track from Mushishi, an anime we

shared an appreciation of, I started my 18th improvisation.

I began with a broad, silent sunset in my mind, trying to reach out through the sensitivity of

sounds to sooth the Other. A sudden awakening strum was followed by a second weaker and

more hesitant one, to appeal through its contrasting vulnerability. Did it work? I began

spinning notes established thus far in automated fashion, keeping to the mood and sound

palette. Were the sounds becoming too abstract for Ks? If I could not vary my musical

parameters as widely due to my audience, I must broaden other parameters, like expression. I

ran out of ideas sooner than usual, having to keep to a musical palette I hoped was appealing

to Ks. His eyes were closed. Was he bored, in a trance, enjoying himself? I started a new

section with a more predictable and faster bass ostinato pattern. Then I broke out of it and

tried something new but still within the tone palette. At the end, I recalled the initial motif and

emotional state and faded into silence.

I turned off the recorder and turned toward Ks.

'Well?'

'It sounds like Zephyr,' he said, mentioning a piano work I wrote a few years back.

'Does it?' I asked, disagreeing but keeping my tone neutral. 'So is this improvisation what

you are looking for?'

'Not really,' he admitted. So I guessed wrong.

Covering my disappointment, I asked, 'Why is that? Doesn't it sound like Mushishi, and

doesn't it sooth you?'

'Yeah, but yours sounds less focused whereas Mushishi sounds more to the point and more

intriguing. Guess it's also because it's short.'

I was reminded of reading somewhere that improvisation often sounds like pointless

rambling. So does jazz sound to me, but isn't rambling part of the point?

'So what is it you are looking for then?'

'Something catchy for my mood. Easier to listen to.'

So my diagnosis was correct - he was pissed, but my prescription had erred. It occurred to

me how most of us only begin to know what we prefer after living through an experience from

which to establish a basis for comparison.

'Why don't I do another improvisation now, and you see if you prefer it,' I said on the spur of

the moment, already mentally arming my arsenal of popular music sounds and patterns,

which I find pales in comparison to my full complement of musical knowledge and skills.

Nevertheless, the time and space was not my own now, so I intended to try.

'Ok,' Ks replied, seeming more enthusiastic as his participation became more evident.

As I played, I couldn't help feeling how cliche the sounds were; they reminded me of National

Day songs I used to play in school. Regardless, I still enjoyed the effort, technical and

emotional, of bringing music to life, so long as Ks enjoyed it. I felt limited by the established

language. Added to this was the feeling that I had not created something interesting to listen

for. I concentrated again on aspects that I could explore still, such as expression and limited

key changes. I found I could make a mistake by deviating from the established style of the

music. In expected fashion, I recalled material from the first section to round off the piece.

'Well?' I asked a second time.

'...sounds better to my ears, more rhythmic, but as a piece does not intrigue me. I prefer

guitars and drums to piano in general and this piece sounds quite cliche.'

'But didn't you say you want something catchy to listen to?' Quietly I agreed it was cliche,

but only because I thought that was what he wanted!

'Yes, but at the same time, it must also have something unique to listen for,' he said

reflexively, 'like the first movement of Moonlight sonata, the heavy and tragic feeling.'

Another assumption of mine about his musical tastes dashed.

And why my great attempt to reach out to the other beyond my Self, which had seemed so

important to me, to reduce my desires and needs to accommodate one other? And my

answer: living this space in this moment together, it just seemed right that any music played

should also permeate this shared space, a precious moment of shared experiences and

emotions connected by the conduit of sounds as semiotics of emotional thoughts.

In my mind, I wondered in such improvisations that are within the frame of established

musical language with its appending expectations of audiences well-informed of the style,

how much is actually free? How much of the Self is lost? Or do the social expectations of

music create a fused style shared by all, creating a greater sense of expression and meaning

through shared embodiment and participation?

In comparison to my solo improvisations, I seemed to have lost part of my identity while

trying to resonate with the other, and despite attempts to reach out to connect with others, I

may never resonate with them as much as the inner resonance I can achieve within myself. The distance is not a physical one, but a mental one brought about by diverse social and cultural experiences.

From Improvisation 18

Looking back at this and several encounters with the Other - friends, students and music educators, what seems clear to me are the multilevel interactions and negotiation between performer and audience - the complex, cyclical dialogues that are intangible and yet so tangible in shaping the outcome of free improvisation. The social aspect of improvisation is evident in performances that involve both the Self and the Other. Dialectical hierarchies, perspectives and contexts between performer and audience result in the implicit negotiation of the resulting musical product.

What seems to be a purely intellectual process depends on physical processes such as social interactions, and interactions with objects and symbols, and the physical environment (Vygotsky, 1978). Intellect and physical processes rooted in the external social world in any activity, including music making, are inseparable, as cognition may be shared among individuals through the mediation of objects, tools, symbols, and signs. My audience impacted upon my free improvisation through tangible and intangible cues and my perception of them. In the process, we reached for mutual understanding and compromised.

Engeström, Miettinen, and Punamäki (1999) demonstrated how dialectical relationships among mediational artifacts, stimulus, response, and social interactions may be mapped onto a mediational triangle. Burrows (2004) further proposed a model specifically for music improvisation in an attempt to show the hierarchy of mediations in the musical context, where the improviser in a group performance must react to aural stimuli and contribute while taking into account the group members' contributions. Cognitive distributions occur between musician and instrument, between musicians, between musicians and the music, among others. Contrary to Engestroem's mediational triangle where the factors involved are related at the same level, Burrows' model shows the musical object that is being constructed as not just the object of the group activity, but also the mediational artifact central to the activity that mediates interactions among players. It shows the musical exchange between individuals - via mediational artifacts such as instruments and sounds - through the central shared audio space (central mediational artifact), which is like a nexus for distributing cognition (Burrows, 2004, p. 8).

Summary

I concur with Burrow that the musical object is a nexus through which other aspects engage in cyclical, dialectical exchanges. Taking into account the different setup of my improvisational practice, I placed Musical Object in the centre, surrounded by the other aspects. Finally, I constructed a circle to envelope all in Context (Figure 5).

The final diagram represents my experience of living the free improvisational process. Within the outer circle is a sea of interactions that involve all aspects, with the musical object placed within the inner circle to describe its position as not just a mediational aspect at the same hierarchical level as other aspects, but also the nexus, result and feedback of interactions.

In this context where I perform with an audience, free improvisation rejects music on a pedestal, where the audience tries to reach out to, understand, and aspire to. Free improvisation in collaboration becomes the potential medium for equal, level exchange, where the audience has a strong influence on and negotiates with the free improviser the outcome of the musical product - the mediatory factor between the two - through shared time and space. Free improvisation, due to its contextual flexibility and mutability, has the very nature to serve as communication. Free improvisation with the Other becomes music to communicate, not to barricade; it becomes the mediator connecting between people.

The Loyalist and the Rebel

Loyalist: I would like to begin with the challenge of conventions. There is a lot of crossing

over of hands. Why? Shouldn't you keep to the space allocated to each of your hands?

HH: I feel that I need to explore, to find new automated ways of playing that is convenient

and effective. By playing around I found this configuration that connects between my Body,

Instrument and my Mind. It is a game of expediency.

Rebel: Yes. A reaction against what has always been prescribed allows for new inventions

and a sense of moving forward, like how you used the back of your hand on the black keys to

create a new effect.

HH: The backward slide? Yes I was experimenting at home and got a kick out of discovering

this, so I modified and used it just now. And I find that too many conceptions prior to

improvising may constrict rather than guide my playing. In any case, systems and structures

emerge and evolve naturally in the process of free-improvisation.

Loyalist: But you can't possibly play off-the-cuff! You are biased by your social-cultural

influences and experiences, which enables you, with the required knowledge and skill, to

define your improvisation. I can hear Debussy and Ravel in your playing, to begin with.

There's also a particular biting wit found in Prokofiev and Kabalevsky...

HH: No doubt my existing knowledge and skill are very important as staple for my

improvisation, and all those technical exercises by Czerny and Hanon certainly created an

impact.

Rebel: (Impatiently) Yes, yes, existing knowledge and skill are important, but how do you

move on? There is an arsenal of patterns that you call into play each time, but at the same

time don't you also try to break new grounds because you don't want to repeat the old?

HH: I agree, but comfort zone is still very important to me. It is within this comfort zone that I

try to break out of the system, so that it creates meaning and significance in relation to the

rest of the, should I say, more conformist music. This more conformist aspect can also

become the basic semantics of communication with an audience with similar musical

preferences.

Loyalist: You also feel a sense of responsibility to what you have played before, and try to be

consistent as you forge forward.

Rebel: Though you also break out of consistency when things get boring.

HH: Yes. It is often a moment-to-moment decision, where I think about what to do next before

I bore myself and the audience. In fact the change aspect is really strong, and I have

categorized them according to common features. They include macro sections, within which

are micro-organizations such as elaboration, contrast and repetition...

Loyalist: Which are based on your existing practices...

Rebel: ...that evolve over time.

Loyalist: (Waving it off) Regardless, within the improvisation you just performed is a style

that is clearly homogenous in terms of tonality, rhythmic patterns, textures and structure. It

demonstrates strongly your need for conformity.

Rebel: But within this perceived homogeneity are also changes in sound patterns. For

example, you moved from mid to high range because you want to break out of existing

patterns, without which the music cannot proceed...

Loyalist: But it still falls within the framework of homogeneity...

HH: Yes, there is constant tension between conformity and change, to break barriers and yet

remain relevant.

Rebel: So is there a lot of experimentation and finding out how it will finally sound? By doing

something where there is no precedence for comparison, there are no mistakes. It boosts your

confidence for creativity.

Loyalist: Or figuring out how it'd sound, knowing it would sound good, and executing it?

While you can make mistakes following a prescribed style, you usually achieve what you

intend to. It boosts confidence in your capability.

HH: Can I then strike a balance between the two, so that I can have both creativity and

capability? In the final balance, perhaps there are mistakes, but these mistakes will be seen as

opportunities to create new grounds. But that which is experimental and new soon becomes

established and old, and something newer needs to come along. It is the constant regenerative

nature of free improvisation. Therefore the two of you are not that different.

(Loyalist and Rebel look repulsed.)

HH: But other than being rather organized by nature, the homogeneity you mentioned earlier

regarding my playing reflected my thoughts and emotions in that moment. It may not be so in

other Contexts.

Rebel: (Knowingly) Ah. So rather than conforming, you are articulating your Self in that

moment. You are expressing yourself? There is more than one you?

HH: I suppose. I improvised in this style because I know you have Western Classical

background. I reacted to the audience. It was a conscious decision before I started, and also

because of my own Western Classical background.

Rebel: So you would improvise differently if we had long hair and wore skinny jeans?

HH: (Laughs) I can only say that preconceived notions of my audience affected the resulting

improvisation, certainly more so if they indicate their musical preferences verbally, though

their perceived reactions during the performance also affected me. For instance, I ended up

playing something very easy-listening for a frustrated friend with no formal music training,

and something fast-changing for my students in their teens.

Loyalist: So you conformed to Other's needs.

Rebel: But you also defied Other's needs to create some space for your own expression.

HH: I did both. I compromised. In the process, I mediated between myself and the audience

within shared space and time. I think that the impact of the audience is proportionate to the

extent of preconceived disparity between me and them at the moment of performance. If my

listeners were five-year-olds, my improvisation would be very different, and I would

constantly check their responses to determine their engagement. It all boils down to Context.

It becomes less of self-expression, and more of shared-expression.

Rebel: Let's talk more about the expression of the Self. By expanding your musical

playground, being part of this process of discovery, whether alone or in social settings, is it

also not therapeutic, because it allows you to break out of a cage of established practices and

explore new places?

HH: Of course, and associated with this is the idea of releasing oneself through performance

arts.

Loyalist: (Grumpily) Let's not forget that in order to break out of this cage to enjoy freedom

and expression, you need to have the cage first.

HH: And all automated aspects of my playing came about from these systems, schemas, or if

you like, cages of patterns developed from traditional practices. It is the existence of

automation that releases the focus of my consciousness for self-expression.

Rebel: (Impatiently) But with all your well-established automations, do you not feel that your

improvisation has reached some kind of stasis?

HH: (Hesitantly) This question is related to the static way of my life now. I do feel that I have

reached a stasis, and may remain so until I venture to gain new perspective and experiences.

But in life we form a cage, break out of the cage, go into a new cage, and then break out of it

again. So is there stasis?

Loyalist: (Wisely) Most people prefer one cage. It is very safe.

Rebel: (Annoyed) Back to self-expression, is there not an element of catharsis? Because of the

physiological element in the physical act of performance, do you feel release from daily

tensions?

HH: I do. When I am down or frustrated, one avenue I would take to mediate my mental state

is free improvisation. That does not mean that I will bang on the piano if I am frustrated or

play gloomily if I am sad. In both cases, I may play calming music or whatever else it takes to

make me feel better at the end. This is easy to do given the mutability and flexibility of free

improvisation. This is also what I mean by mediating my Self through sounds.

Loyalist: In other words, there is no direct correlation between music and state of mind. So

you agree that the cathartic effect of music is brought about through the integration of the

cognitive, affective, psychomotor, and...

HH: I call these categories the six aspects of involvement, and when they come together to

interact to define my improvisation through tension caused by conflicts and subsequent

compromises between my Rebel and Loyalist tendencies, I call it Immersion.

Loyalist and Rebel: But these conflicts and compromises as a result of us is a part of daily

life, is it not?

HH: Therefore free improvisation can be seen as snapshots of life.

(Based on actual discussion with Drs Eugene Dairianathan, Kelly Tang, Lum Hoo and

Peter Stead after my free improvisation performance at the National Institute of Education,

Singapore)

From Post Improvisation 19

Free Improvisation as Musical Living

Through the multilevel experience of actively encountering and participating in a musical process that creates perpetual tensions and resolutions - through dialectical arguments between distinct aspects engaged in Loyalist and Rebel instincts - the meaning of free improvisation is found. The sense of dynamic, interactive involvement within the validity of the experience constructs a kind of musical meaning that is experienced through the continuous, cyclical process of self-construction and representation through the ongoing restructuring, definition, and representation of identity. In other words, one's identity and self-definition is negotiated within the dialectical phenomena of free improvisation, through which ontological meaning is experienced within its transformational potential (Sansom, 2007). From this perspective, meaning is not created from the result of a practice's existing, underlying structural relations, but in overcoming tensions and conflicts arising from the constraints that are imposed upon the performer's awareness. Meaning is found in conforming to these constraints that represent the 'existing order' of things while at the same time challenging them in the attempt to subvert that order. By exploring and experimenting within the governing order or restraint of improvisation through interaction between the Self and the various aspects in a given context, one's identity is defined.

Napier (2006) sees this tension as arising from the demands of reproducing inherited models of expression on one hand, the need to reflect contemporary subjectivity on the other, and yet retain continuity from the former models. It requires re-representation of previously acquired templates, and its value may be understood with reference to a specific intellectual and artistic social-cultural angle. Therefore, although a performance is important, but the journey before that performance as much so, for the meaning it creates in a particular performance is the culmination of a long period of ongoing creative and personal development for the free improviser. Free improvisation is therefore an ethnographic musical journey, where meaning can be found in its evolutionary and revolutionary quality that comes with change. Bulow's Impressions after an Improvisation succinctly summarizes the notion of free improvisation as a cyclical process searching for ontological meaning - "Searching for oneness in an endless circle" (Bulow, 1981-1982).

In a final move, I constructed a diagram to sum up my experience with free improvisation (Figure 6).

Wrapped in a particular context, first I 'Do', striking the keys as various aspects of involvement interact in perpetual tension at different levels of consciousness. At the same time, I 'Experience' the doing as the sounds construct and negotiate themselves into macro and micro organisations of coherence. As I experience, I 'Assimilate' the sounds into part of the whole musical tapestry and decide on the next move. All these are guided by the Context and my acquired musical knowledge, preferences, skill etc. that are socially and culturally informed. When all these come together, I experience immersion in the moment. This moment-to-moment immersion becomes a kind of Musical Living. It describes the primary purpose of free improvisation - seeking ontological meaning through the cyclical process of perpetual Self-construction in relation to the Other, inner world in relation to the outer, meeting and understanding the Self through continuous discoveries and rediscoveries.

Bringing it back to Music Education

Returning to my role as a music educator, what are the possible implications?

And my answer: for a teacher conducting general music and creativity programs, free improvisation provides an avenue for promoting self-expression by nurturing creativity and communication with oneself and others.

It promotes creativity because:

It promotes communication because:

I imagine a class where improvisations could be developed without criteria, where students are encouraged to self-express and live through music within a dynamic context that is shaped and negotiated by all participants. For this to occur, instead of creating a situation in which there is a predetermined outcome and the sum of the parts is already known, music educators must be comfortable presenting unpredictable situations and exploring open-ended possibilities (Borgo, 2005, p. 173).

If music educators agree that free improvisation is a means of musical knowing, a means to engage students in music making regardless of musical background and proficiency, that free improvisation as a discipline is not exclusive to music but pervasive in life, and that it stems from and encourages self-expression, then free improvisation should be taught as an essential activity in music classes.

Stephanie Sun is a Singaporean Chinese pop singer and songwriter. The song Tian Hei Hei, which she sings in both Mandarin and Hokkien, is written by Singaporean music producer and composer Lee Shih Shiong. It is an adaptation of a Hokkien folk song, and describes the recollection of innocent and simpler childhood days and the urge to return to it.

Bailey, D. (1992). Improvisation: Its Nature and Practice in Music. New York: Da Capo Press.

Blum, S. (1998). Recognizing improvisation. In Nettl B. and Russell M. (Ed.), In the Course of Performance: Studies in the World of Musical Improvisation (p. 27-45). Chicago & London: The University of Chicago Press.

Borgo, D. (2005). Sync or Swarm: Improvising Music in a Complex Age. New York: Continuum.

Bulow, H. T. (1981-1982). Impressions after an improvisation, Perspectives of New Music, 20(1/2).

Burnard, P. (2007). Routes to understanding musical creativity. In Bresler L. (Ed.), International Handbook of Research in Arts Education (p. 1199-1214). Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer.

Burrows, J. B. (2004). Musical archetypes and collective consciousness: Cognitive distribution and free improvisation, Critical Studies in Improvisation, 1(1).

Conquergood, D. (1991). Rethinking ethnography: Towards a critical cultural politics. Communication Monographs, 58, (p. 179-194).

Cook. N. (1990). Music, Imagination, and Culture (p. 112-113). Oxford: Oxford UP.

Ellis, C. (2004). The Ethnographic I: A Methodological Novel About Autoethnography. Walnut Creek: Alta Mira Press.

Engeström Y., Miettinen, R., and Punamäki, R-L. (1999). Perspectives on Activity Theory. New York: Cambridge UP.

Hall, E. T. (1992). Improvisation as an acquired, multilevel process, Ethnomusicology, 36(2).

Napier, J. (2006). Novelty that must be subtle: Continuity, innovation and 'improvisation' in North Indian music, Critical Studies in Improvisation, 1(3).

Nettl, B. (1998). An art neglected in scholarship. In Nettl B. and Russell M. (Ed.), In the Course of Performance; Studies in the World of Musical Improvisation (p. 1-26). Chicago & London: The University of Chicago Press.

Porcello, T. (1998). "Tails out": Social phenomenology and the ethnographic representation of technology in music-making, Ethnomusicology, 42(3).

Pressing, J. (1984). Cognitive processes in improvisation. In Crozier W. R. & Chapman A. J. (Ed.), Cognitive Processes in the Perception of Art (p. 345-363). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Pressing, J. (1988). Improvisation: Methods and models. In Sloboda J. A., Generative Processes in Music; The Psychology of Performance, Improvisation and Composition (p. 129-178). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Pressing, J. (1998). Psychological constraints on improvisational expertise and communication. In Nettl B. & Russell M. (Ed), In the Course of Performance; Studies in the World of Musical Improvisation (p. 47-67). Chicago & London: The University of Chicago Press.

Roth, W.-M. (2005). Auto/Biography and auto/ethnography: Finding the generalized other in the Self. In Roth, W.-M. (Ed), Auto/Biography and Auto/Ethnography: Praxis of Research Method (p. 15). Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

Sansom, M.J. (2007). Improvisation and identity: A qualitative study. Critical Studies in Improvisation, 3(1).

Temperley D. (2007). Music and Probability (p. 151-156). London: The MIT Press.

von Emmel, T. (2005). Learning to improvise in somatic performance: Relational practices and knowledge activism of bodies improvising (p. 111-137), Doctoral dissertation, Fielding Graduate University, Santa Barbara, California.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in Society. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

About the Author

Ng Hoon Hong is a music teacher with the Ministry of Education, Singapore and lectures at National Institute of Education, Nanyang Technological University. As a teacher cum researcher, Hoon Hong hopes to establish immediate relevance and relationship between educational research and authentic teaching practice. His research interests lie in improvisation and creative music-making in the classroom. Besides conducting workshops in the field of creative music teaching, he has also presented his paper on free improvisation at the ISME conference.

|