International Journal of Education & the Arts | |

Volume 1 Number 3 |

September 11, 2000 |

Using Namibian Music/Dance Traditions as a

|

Ngoma: A philosophical departure pointThis term summarizes the holistic connections between music, dance, other arts, society and life force. It encapsulates the notion of power in communal performance, and it draws from indigenous music and dance traditions for color and vitality. Ngoma refers to musical performance and musical instruments, dance, humankind, spirit possession and the world as an organic whole (Bjorkvold 1992, Blacking 1985). It signifies the unified experience of music and dance and their links to other arts, to society, to life-force and it implies that performance centers on the power created by communal participation. Ngoma has been described by a Silozi-speaker (Lunenge 1995) as the communication between drums and spirits—impossible without dance.The holism of arts in many African cultures is relevant to fundamental aspects of life. Music, dance and other arts are functionally interwoven into everyday life and festive occasions as well as ordinary work. In performance, the individual becomes part of community, but also part of the music, linking earth to heaven, past (via ancestors) and future (via children). Performance as ngoma implies that music/dance have a purpose and function larger than themselves. They prepare individuals and community for the tasks intended, whether mundane or spiritual. By means of this preparation the performance encourages total involvement, which in turn feeds back as excitement and enjoyment, leaving a sense of satisfaction. A framework for understanding arts in southern African culturesShould teachers require insight into a culture's songs, rituals and dance, a conceptual framework of questions allows one to approach that culture constructively. In my research I normally begin by asking very general questions about when and how people make music and dance. Questions are framed around stages of life or functions that musical practices have within that particular culture, because these are common frames in African contexts. From this general background, one can move towards more specific observations in terms of the musical performance with questions that normally refer to structural organization, tonal organization, rhythmic organization and quality of sound (Arom, 1989, 1991; Chernoff 1979; Kubik, 1990, 1993; Tracey 1990).Based on the work of Adshead (1988), Bartinieff (in Royce 1977), Hanna (1979), Thompson (1974) and Keali'nohomoku (1997), the following are salient features of an observation and description of dance:

I generally use the above as a general framework to guide my personal observation and the questions I ask people or myself. This may differ according to the context of the particular performance. From answers and observation the prevalent categories of performance within that culture become clear. Although not final, this begins to show us the conceptual framework by means of which that culture organizes its music and dance. I aim to try and understand peoples' own conceptual framework rather than impose one based on my own concepts. In Table 1 below, click on the characteristics outlining possible questions and some of the answers I have found in Namibian practices. Short illustrative video clips can be viewed. |

Table 1

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

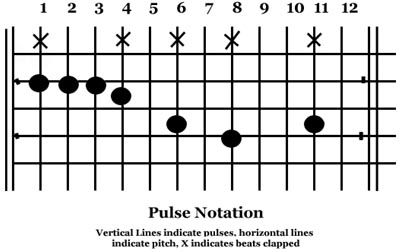

Materials—A Suggested Form for Sound and MovementThe high demand for teaching materials in different African languages prompts discussion of how this is to be presented. Because western notation proceeds from a different conceptualization of music to that of many African societies who make provision for a margin of pitch tolerance as well as great rhythmic complexity, it is not an ideal vehicle for notating African music. Note values in western notation indicate duration of sound, whereas the space between sounds and the moments of impact are more important in African music. In drumming music it is not only the rhythmic patterns which are of importance, but also the timbral- melodic effects and the movements involved. A system is needed where both music and movement can be combined in a score, in the same way they are linked in the minds of performers.A transcription can be reduced to the simplest form recognizable to members of the community. A transcription need not be detailed, but should reflect the central characteristics of the music being transcribed. One would try to establish which elements the practitioners of the culture deem essential to the performance, elements that undergo relatively minor changes as they are passed from one generation to another. The score therefore reduces relevant elements to a point where only elements common to all realizations of that particular music are notated. Transcriptions can be enhanced by verbal descriptions which provide deeper insight into the context and meaning of the performance, including variations to the basic form. Where a notation is unable to convey expression, or individual movements and deeper experiences such as trance, a description provides a verbal sketch of the event. Vernacular terms provide the frame and indicate the peculiarities of the event. Pulse notation works well in the Namibian context because:

|

|

Having taken all these into consideration, a transcription may look as follows:  Suggestions for implementation of music and dance as ngoma in the classroomOnce a teacher has gained information on a cultural practice and has materials for use in the classroom, attention needs to be paid to the mode of implementation. While there are many possibilities, an approach located within the spirit of ngoma would take cognizance of the following three cornerstones that underpin this approach.

|

A Final WordFinally, traditional arts practices can contribute to learners' creativity, perception and understanding of life and their cultural identity. The classroom in which the arts are treated as ngoma may become a place where communal, connective, relevant and ultimately enjoyable learning takes place. Teaching as ngoma may require substantialreadjustment to the standards by which teachers measure the success of their programs. It is not only what a performance looks or sounds like to them (teachers) that is important, but what the performance feels like to learners. Effectively implemented, the notion of arts education as ngoma is a means of linking the wisdom of the past to modern modes of expression and to the wider world. ReferencesArom, S. (1991). African polyphony and polyrhythm: Musical Structure and Methodology. (1989) Translated from the French by M. Thorn and R. Boyd. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Arom, S. (1989): Time and Structure in the Music of Central Africa: Periodicity, Meter, Rhythm and Polyrhythmics. Leonardo:, Vol. 22:1. 91 - 99. Bjørkvold, J-R (1992). The Muse Within: Creativity and Communication, Song and Play from Childhood through Maturity. (1989). Translated from the Norwegian by H. Halverson. Aaron Asher Books. New York: Harper Collins. Blacking, J. (1985). The Context of Venda Possession Music: reflections on the Effectiveness of Symbols. 1985 Yearbook for Traditional Music. Vol. 17: 64 - 87. Blacking, J & Kealiinohomoku, J. (Eds.)(1979). The Performing Arts: Music and Dance. The Hague: Mouton Press. Chernoff, J. (1979). African Rhythm and African Sensibility. Aesthetics and Social Action in African Musical Idioms. Chicago: Chicago University Press. Hanna, J. L. (1979). To Dance is Human. A Theory of Nonverbal Communication. Austin and London: University of Texas Press. Kealiinohomoku, J (1997). Structure presented in a workshop at Confluences: Cross-Cultural Fusions in Music and Dance. First South African Music and Dance Conference incorporating the 15th Symposium on Ethnomusicology. University of Cape Town, 15 - 19 July 1997. Kubik, G. (1990). Drum patterns in the "Batuque" of Benedito Caxias. Latin American Music Review, Vol. 11: 2 Fall/Winter. University of Texas Press. Kubik, G. (1993). Manual for Teachers: An Introduction to the Study of African Music. Manuscript for the Ministry of Basic Education & Culture, Windhoek. Mans, M. E. (1997) Namibian Music and Dance as Ngoma in Arts Curricula. Unpublished thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. University of Natal.

Mans, M. E. (1997) Discovering some of the Characteristics

of Namibian Dance/Music. IN: Fourie (Proceedings Compiler).

Confluences: Cross-Cultural Fusion in Music and Dance.

Proceedings of the First South African Music and Dance

Conference incorporating the 15th Symposium on

Ethnomusicology. 16 - 19 July 1997, University of Cape Town.

pp. 273 - 289. About the AuthorDr. Minette MansDepartment of Performing Arts University of Namibia Tel. + 264 61 206 3896 e-mail: mmans@unam.na Dr Minette Mans is Associate Professor at the University of Namibia, where she heads the Performing Arts Department. She is involved with teaching Music Literature (mainly African), Classical Guitar and Body and she publishes widely on topics relating to music, dance, culture, identity and education. Although previously deeply involved with arts education reform in Namibia, she now focuses on policy development and field research. Her present area of research is the documenting and analysis of Namibian musics and dance as part of an extended project covering all the main cultural groups of the country. This information is currently being developed into books for schools, videos, and CD ROMs in service of education. |

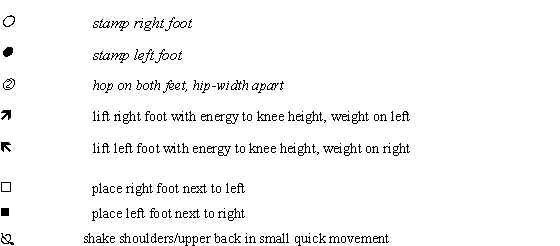

for a full right hand beat

and

for a full right hand beat

and  for a half right hand beat. The same symbols filled in

black refer to the left hand, i.e.,

for a half right hand beat. The same symbols filled in

black refer to the left hand, i.e.,  and

and

.

.