International Journal of Education & the Arts | |

Volume 2 Number 3 |

June 10, 2001 |

Theoretical Foundations for an Art Education

|

|

Pictures of Earth from the moon and Coca-Cola advertisements

with young people from various nations singing "We are

the World" highlight the sense that we are now all

interdependent. In the words of the song made famous by

Disneyland, an icon of globalization, "It's a small

world after all."

Hannerz (1996) writes, "Globalization is a matter of

increasing long-distance interconnectedness.... much of the

world is now self-consciously one single field of persistent

interaction and exchange" (pp. 17, 19). While groups

of people once lived geographically apart from one another,

and barely knew of each other's existence, different peoples

are now often in each other's immediate presence. Even

where they are not physically rubbing shoulders, the

proliferation of mass communications media ensures that the

images of others regularly intrude and circulate without

regard for physical distance. Morgan (1998) writes, Simply put, the notion of globalization is the assertion that a worldwide system of economic, cultural and political interdependencies has come into being or is in the process of formation. Older systems that organized the distribution of political, economic, and cultural power, generally on a national basis, are now being superseded by a more international system or set of forces that span the planet. (p. 2)Barber (1996) exempifies global culture with three M s: "MTV, Macintosh, and McDonalds" (p. 4). Other sites include theme parks, the Internet, television, tourist sites, shopping malls, and a plethora of consumer goods. As part of a worldwide consumer culture, each is driven by the now triumphant and relentless logic of the market place. Increasing numbers of people all over the world now experience the same complex repertoires of print, celluloid, electronic screens, and billboards. For art educators concerned with visual culture, and not just fine art (e.g., Barnard, 1998; Duncum & Bracey, 2001), this wide range of imagery is grist to the mill because, as Debord (1967/77) was able to write a full generation ago, "All of life presents itself as an immense accumulation of spectacles. Everything that was directly lived has moved away into a representation" (p. 2). Predating a host of postmodern theorists, Debord argued that, whereas with an earlier phase of capitalism there was a slide from being into having, there is now, with what he called the society of the spectacle, a slide from having into appearing (p. 5).

In this article, I outline theoretical foundations for an

art education that engages with global culture and offer

some guidelines for classroom practice. To commence the

first task of building a theoretical foundation, it is

necessary to sketch some of the widely held, reactionary

views about global culture. Reactionary views are presently

the most likely to inform the thinking of art educators.

These views have popular appeal and most art educators have

been educated to value unique and individual expression and

to despise the sameness of mass production. |

|

The Theory of Cultural Imperialism Global culture certainly arouses intense feelings of disgust. This is captured, quintessentially, by one French critic's description of Euro Disneyland as "cultural Chernobyl" (Perry, 1998, p. 73) and the status the soap opera "Dallas" earned in Europe as a "hate symbol" of "cultural emasculation" (Morley & Robins, 1995, p. 53). Global culture arouses fears of "the production of [a] one world mind, one world culture, and the consequent disappearance of regional consiousness flowing from the local specificities of the human past" (Pret in Morley & Robins, 1995, p. 70). These ideas are based on a view of cultural transmission known as cultural imperialism. It is said that in the global village, everyone is subject to the same universal culture which is transmitted by world-wide communication networks. This is sometimes called the Trojan Horse model of cultural transmission (Morgan, 1998). A nation state is said to accept cultural goods as a gift only to find that it has imported a host of previously concealed values and beliefs that ravage local customs and culture. This view is also known as the hypodermic model of cultural transmission; culture is said to be inserted into a foreign body that posses few, if any, natural defenses (Morley & Robins, 1995). According to these views, older systems based on nation states have or are thought to be breaking down, and global imagery takes up the space that would otherwise be available to home produced cultural goods. The circulation of imported cultural goods is said to not serve the interests of the host country because imported goods refer to foreign situations and are imbued with foreign values. Because much global culture is derived from the United States, the cultural imperialist view of global culture is often referred to as Americanization (Featherstone, 1995). Americanization and mass consumer culture is seen as a proto-universal culture which piggybacks on the economic and political domination of the United States. The United States is seen as thrusting its hegemonic culture into all parts of the globe and to have a corrosive homogenizing effect on the integrity of national and local cultures. This position is, of course, developed from the perspective of the importers of cultural goods (Appaduari, 1990). For the exporters of culture, however, the theory of cultural imperialism is based on the assumed inevitability of modernization (Featherstone, 1995). All local cultures, it is believed, will eventually give way under the relentless modernizing drive of American cultural might. All cultures are assumed to be linked together in a symbolic hierarchy, and it is believed that each non-Western nation will eventually become modernized and move up, so to speak, the cultural ladder to duplicate or absorb US culture. Three theorists most noted for this general position are Barber, Baudrillard, and Ritzer. Barber (1996) calls global culture "McWorld," seeing in the logic of the capitalist markets by which it is driven, the twilight of national sovereignty and the destruction of democracy. It paints the "future in shimmering pastels," he says, but "every demarcated national economy and every kind of public good is today vulnerable to the inroads of transnational commerce"(pp. 4, 13). Baudrillard (1987) argues that since global culture is everywhere the same, we have lost a sense of place, and since global culture floats on unanchored signifiers, we have also lost a sense of time. We are, he argues, thereby stripped of a sense of identity and with it the possibility of agency. Such is its seductive power that global culture renders us immobile. Combining the two most prominent icons of global culture – McDonalds and Disney - Ritzer (1998) has coined the term McDisneyization to describe what he sees as the values produced by global culture: efficiency, profit and standardization. With these characteristics in mind, Ritzer charts a general decline of cultural standards, condemning, for example, theme parks, packaged tourism, the Internet, and popular television programs. He laments that as nations surrender to the conformity of global culture they lose their personality. Like Barber and Baudrillard, he is deeply nostalgic for an older, quieter, slower world. Indeed, such nostalgia is widespread, and it finds expression in the assertion of national cultures as somehow authentic. Increasing contact with other cultures, be it face to face or through imagery, has led to a disturbing sense of engulfment. This, in turn, has lead to a retreat into the security of one's own cultural traditions and the assertion of the integrity of national cultures (Feathersone, 1995). This can be seen in the growth of the heritage movement with its nostalgia for past emotional harmonies (Lowenthal, 1997), but it has its worst practical consequences in the often violent reactions of many religious and ethnic groups to other groups and, notably, to anything Western (Barber, 1996). Despite its popularity, the theory of cultural imperialism is seriously flawed. A view that sees globalization as bound to an inevitable process of Western modernization is strikingly old-fashioned. It must deal with the fact that while the US continues to be the chief exporter of cultural goods, many other exporters of culture exist. Depending upon where one lives it is reasonable to speak, for example, of the cultural hegemony of Japan, China, and India (Appaduari, 1990). No single cultural hierarchy exists, or is likely to. In the West the fusion of technological systems is leading to an ever-greater concentration of cultural capital in a few hands. This is a deeply worrying development for access to information and the operations of democracy, but at the same time new technologies are also enabling more and more local productions and their export across national borders (Barker, 1997). The critique against global culture as homogenizing and destructive turns out to be very familiar. It represents a re-run of a very old critique, the high culture critique of popular culture and mass society (Alfino, Caputo, & Wynyard, 1998). Instead of being confined to the competing cultures of one country, however, the critique, like the popular culture it attacks, has gone global. Now, though, instead of upholding high culture as authentic and uncontaminated by commercial values, it seeks to defend national cultures in the same light. Where high culture offered a source of wisdom and standards worthy of emulation, now national cultures are seen to offer a sense of secure identity in a fragmented world. This is despite the fact that national cultures are often decidedly popular in content and certainly not fixed entities. Moreover, they never were fixed. If there is one thing certain about traditions it is that they are as adaptable to changing circumstances as humans appear wired to create new circumstances. It is one thing to seek a sense of self through a negotiation with the history of one's own living space; it is quite another to see the past as never having been influenced by others. Groups of people confined to and by the places to which they belong, groups unsullied by contact with a larger world, may never have existed, at least not for long (Appadurai, 1990). If they ever did, they certainly do not now. In the pre- modern world many, diverse cultures were often physically separated, but now the disparate array of cultures "is no longer simply out there, but also within"(Morley & Robins, 1995, p. 115). Migrations of people, either as tourists, laborers or refugees, have never been greater, and there is perhaps a need to develop a model of travelling cultures whose sense of self is not rooted in a particular geographic space but in mobility (Clifford in Morley & Robbins, 1995). These days, as Gomez-Penna says, "there are no 'others,' or better said, the only true others are those who resist fusion ... and cross cultural dialogue .... hybridity is the dominant culture" (1996 in Congdon, Delgado-Trunk, & Lopez, 1999, p. 326). Most cultures today, Howes (1996) says, are subject to "creolization" (p. 5).

Barber, Baudrillard and Ritzer's critiques, which are alike

in both content and hyperbolic tone, are part of a long line

of cultural critique (Williams, 1958) that advances by means

of exaggerated contrasts, an outsider's position, a view of

audiences as passive, and an idealization of the past

(Duncum, 1990). Cultural imperialism stresses only the

homogenizing tendencies of globalization and ignores its

wonderfully heterogeneous tendencies. |

|

Theories of Heterogeneity Foundations for an art education of global culture can be more appropriately erected on post- structural theories of reading reception and on theories of indigenization and cultural translation. Each of these theories stress heterogeneity and human agency rather than homogeneity and passivity. They stress the diversity, variety, and richness of popular and local cultural practices, which resist and play with the cultural goods of global capital.

Reading Reception Theory Along with McDonalds, blue jeans, and Hollywood films, the spread of Coca-Cola may appear to be a powerful argument in favor of homogenization. In many world regions it has displaced local drinks such as fruit juice, coconut milk and even water. It is promoted as a universal or transcultural product while at the same time being closely identified with the cultural ideals of the United States. Yet as Howes (1996) demonstrates, it is attributed meanings within particular cultures that were never envisaged by its manufacturer. In Russia it is thought to smooth wrinkles; in Barbados, to turn copper into silver; and in Haiti, even to revive the dead. It is often mixed with local drinks to produce new brews, and in many different places people appear to believe that it originates in their own country. The image of Coca-Cola may be made in the USA, but as Howes says, it is remade in many other countries. The theory of cultural imperialism would suggest that each of these countries would adopt the reading position of the US audience, but clearly this is not the case. Instead, Coca-Cola is a site of complex cultural beliefs and values under which the product undergoes strange and unexpected metaphorphoses. Barker (1997) makes it clear that with imported television programs this same process is routine, the rule not the exception. Perhaps this should not be surprising. Many parts of the world – Europe and Australia for example (Morley & Robins, 1995: Willis, 1992) – have long defined themselves as not whatever they imagine America to be like, or what they wish not to be, or not what they fear they might become, or worse still, and paradoxically, not what they fear they already are. Post-structural reading reception theory has taught us to see the variety of interpretations that exists among even a relatively homogeneous audience to identical cultural goods. Such is the variety of interpretation even among such a group that reading is seen as evidence of human creativity. When reading reception is extended to the heterogeneity of the world's nation states the variety of interpretations is extended manifold and in such ways that one is constantly reminded of one's own cultural limitations. In short, just as we have learned not to underestimate the freedom of consumers to make what they will of what they see and buy, so we should not underestimate the freedom of different national populations to interpret identical products and images in widely different ways.

Indigenization and Cultural Translation In Britain during the 1950, for example, American popular images and products were attacked as a paradigm of bad taste and a lack of tradition, yet they were welcomed by the English working class because they could be read in oppositional terms to the "Great Tradition" of English elite culture (Hebridge, 1988). While, American popular culture posed a threat to those who sought to uphold cultural traditions, it was welcomed by those who felt burdened or marginalised by those same traditions. American popular culture wedged open recognition of the class bound complacency of a traditional, elite culture and was a liberating and progressive force. While English elites condemned the American cars of the 1950s in terms of utter destruction - the "Vietnam of product design" (Hebridge, 1988, p. 66), such products made connections with the actual tastes and desires of large sections of the working class for they represented a significant improvement in their material circumstances. McDonalds, arguably the single most important icon of global culture, provides a contemporary example of cultural translation. In his text The McDonaldisation of Society Ritzer (1993) goes so far as to argue that McDonalds has only pioneered what has now become a widespread organizing principle of society, namely the combination of a fully rountinized and invariant production system that has now gone global. However, as Perry argues, it is important to note that "a Big Mac is both a product and a sign"(p. 152). And if we see it as an indeterminate and complex sign rather than a perfect(ly) simple commodity, then it is not standardization and uniformity which assume priority but variation and difference .... and what it signifies slides promiscuously along and across disparate ... locations from which it is read. (p. 154)While Barber (1996) is content to note the appearance of a McDonalds overlooking Tennienman square as a simple sign of the global triumph of consumer culture over ideology, an analysis of the McDonalds in Moscow's Pushkin Square during the early 1990s is suggestive of an altogether more complex view. For Muscovites, a McDonald's Big Mac is now a luxury item. It has become a souvenir to take back in its wrapper to show off to admiring friends in distant Siberian villages. "We had to come," says ... a postal worker ... from the remote north, "Just to see if it's real. (Smart in Perry, 1998, p. 154)While in the U.S., McDonalds is regarded as fast food, Muscovites queue for hours creating the paradox of slow fast food. The situation has allowed hamburger hawkers to act as surrogates for the wealthy dinners prepared to pay a small fortune for delivery to their cars. They in turn are supported by a hierarchy of minders and their bosses who also gather for their cut. Thus, instead of McDonalds being everywhere the same, here it is evidently different; moreover, it is a difference that can be well understood only in terms of Russia's particular history. As Perry argues, while the product and the freedom to report such illegal activity is new, the practices are "both familiar and expected" (p. 156). They represent no more than the illegal, subterranean actions that previously operated in the command economy of the Soviet Union. Instead of representing the triumph of Western capitalism, a peculiarly Russian way of doing business has asserted itself; here McDonalds means Russia as much as it means the USA. In Australia, McDonalds is often referred to as Maccas, which echoes the benign familiarity expressed in other Australian colloquialisms such as Bazza, Johnno, and Gabba. Here the foreign is made familiar by employing a traditional Australian turn of phrase so that McDonalds becomes Australian as well as American. However, Maccas sometimes becomes Chuckas, which refers to vomiting, and can be seen not only as a critical comment on the quality of McDonalds food but a cultural resistance. But is the residence to American culture or a sub-cultural resistance to Australian culture, or both? The transmission of culture from one country to another and cultural translation are not the same thing. Transmission is what happens at a purely technological level whereas the translation of cultural goods involves human agency; translation is a rich, generative process involving the production of a text that may be more or less than, but is always different from, the original. Textual translation involves generating a range of texts that are original in their own right. Whereas the cultural imperialist view is pessimistic, seeing importers of culture as dependent upon exporters, this dialogical view sees importers of cultures as creators of culture. Cultural goods from one country provide only the raw material from which to select, resist, reinterpret, and, in a host of ways, negotiate to form new meanings. Cultural translation is never now just between one country and another, but between many cultures on many levels - including class, ethnicity, religious affiliation, age, gender, not forgetting able bodied and disabled as well as a wide range of psychological conditions each with their own histories and current preoccupations. Creating meaning is like an ever moving kaleidoscope that continually brings new and surprising images into view. This is not to suggest, however, that there are no limits to indigenisation or cultural translation. Whatever undergoes indigenization or translation does, after all, originate elsewhere. Cultural groups are limited to the reception of cultural goods produced by others, and while this can be highly creative, it does not suggest what can be created out of a group's own cultural heritage. Global culture is like a menu that is prepared by others (Errington, 1995). A group can be highly creative in the ways it selects what is on the menu and what it makes of its selection, but ultimately it is limited by the menu itself. Turning McDonald's into "Chukkas" is sardonic and, Perry (1998) would argue, quintessentially Australian, but offering resistance can go only so far in developing identity. For this reason, it is important to develop a sense of one's own cultural background.

A number of principles for dealing with global culture in the classroom arise from the foregoing discussion. First, teachers should begin to engage with global culture. Acknowledging the limitations of global culture for anyone but the cultural producers as markers of identity, is no argument for rejecting a consideration of global culture altogether. Today, many artists draw upon popular global culture and comment upon it. Quite apart from the pop art and hyperrealist movements of decades ago, which commented mainly upon the visual appearance of popular culture, today there are artists working on specific issues raised by the globalization of popular culture. Recent examples from the 2000 Whitney Museum's Biennial (2000) include Teresa Duncan and Jeremy Blake's 1998 video The History of Glamour which explores the iconography of popular culture to create a "grammar of glamour" with waiflike fashion models that, the artists believe, empower women (p. 101). R+M ARK is a multimedia project which includes a website that parodies websites of large corporations. Its aim is to subvert dominant corporate structures like Microsoft, and into its services it presses icons like Barbie and GI Joe (p. 190). Mark Amerika's Grammatron website explores how new narratives are composed in the digital age with the creation of a "hypertextual consciousness" that he sums up with his declaration, "I link therefore I am" (p. 38). Undoubtedly aware of Barbara Kruger's art statement, "I shop therefore I am," Doug Aitken's Electric Earth 1999 video of the desolation of American urban life focuses upon a shopping trolley alone in a car park at night (p. 34). Increasing numbers of art educators appear willing to take the lead of such artists (e.g. Grierson, 1999; Nalder, 1999). But I believe these attempts to address global culture in the classroom often short-circuit genuine engagement. For Nalder, teachers should examine how artists use global culture rather than dealing with global culture directly; global culture is examined through the filter of the art institution, not in terms that youngsters and most adults would recognize. Failing to consider global culture represents a retreat from the kind of imagery that impacts on youngster's minds and emotions. Continuing to focus exclusively on the art of the institutionalized artworld simply denies students their most immediate experiences and pleasures. One example of direct engagement involves Grauer (2000) having her teenage students examine their own bedroom regalia in light of a Coca-Cola sponsored marketing strategy called "the Global Teenager." The students found that they appeared to be much more influenced by consumer culture than they had believed, and they went on to make a sculpture in which they questioned the extent to which they're values reflected the notion of a universal teenager. Could there be such a thing? To what extent did they conform to the picture drawn up by Coca-Cola? A secondly principle is that teachers should engage with their own cultural heritage but should not retreat into it as if it was unchanging and somehow pure. Celebrating the particularities of a place is laudable but viewing heritage as unproblematic and fixed is illusionary. Cultural identity has always been a fluid, work-in-progress affair that has been subject to numerous external influences and is partly comprised of these influences. One example will suffice. Like so many parts of the world now marginalized by centralized economic networks, my homestate of Tasmania, Australia, is dependent upon tourism. Tourism is about presenting a community to others, not as one sees of oneself necessarily, but how a community believes it should offer itself others in order to best extract money. Tourism thereby open's up questions about authenticity, identity, and presentation, and because all tourism is essentially visual it is of special significance to art educators. One local Tasmanian class of Grade 3s (8 year olds) designed souvenirs for tourists visiting their area. (I wish to thank Susanne Cresse for her invaluable help in teaching this class.) The following are examples:

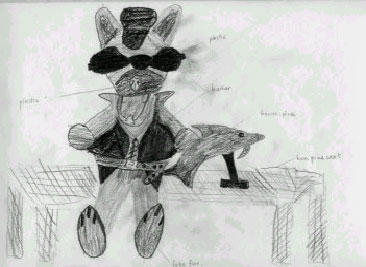

This is a Tasmania Devil stuffed toy dressed as a bike complete with dark glasses and leather jacket.

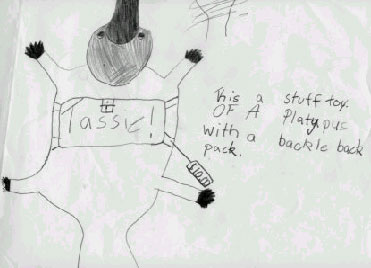

This is a school back-pack in the shape of a platypus with "Tassie" written upon it. Other items with Tasmania written on them included necklaces, glasses, statues, letter openers and knives.

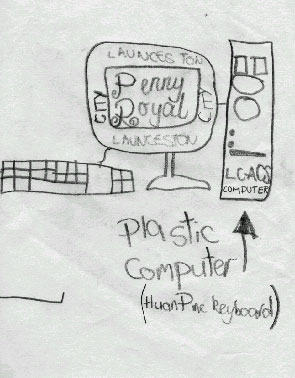

Many items were to be made of Huon pine, which is unique to Tasmania. While in this drawing the computer terminal is made from plastic, the keyboard is made from Huon pine.

Local scenes to be printed on tea-towels and postcards were devised. In this example, a teddy bear is holding up an umbrella because, as the child said, "It rains a lot in Tasmania."

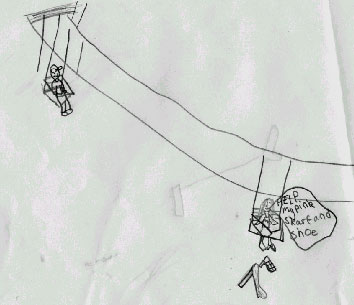

In this example of another tea-towel design, the local chair lift is shown. The children were asked to consider their designs in terms of questions like: What was unique about their small part of the world? Was this easily packaged for others to consume? In what way did their souvenirs reflect their daily lives, and to what extent did they reflect what they thought tourists might value? They were asked to think about what messages they wanted to send about themselves and the places they live.

A third principle is to embrace the complexity of global

culture. It is easy for teachers trained to value the

unique products of individual expression to dismiss global

products as all the same, but doing so misses the point that

numerous meanings are made through the use of global

culture. Concentrating on the products alone is

simpleminded. It is to succumb to appearances only, which

is the very habit of mind condemned by the critiques of

global culture. Rather than concentrating on the similarity

among global products, it is important to recognize the

creativity with which they are interpreted across cultural

contexts. It is necessary to see global images in terms of

their reception, not just as physical things. Stanley's (2000) suggestions for

working with high school students on theme parks are useful

examples. He would have them for example, examine their own

experience of Sleeping Beauty's Castle and compare it with

both Disney's promotional material, textual and visual, and

the original story to see how over time and cultures, visual

tropes and ideas have changed. He suggests that teachers

ask what social pressures have led to the changes

observed.

Fourth, while celebrating

the agency of cultural groups, it is important to be aware

of the limits to agency. Nothing in the foregoing

discussion of global culture as a sign should be taken to

suggest that global culture is not also determined by the

values of the market place or that there are limits to the

making of meaning. We should not forget that however

different diverse cultural groups may read global culture,

the diversity of readings is limited by virtue of global

culture having been prepared by the global corporations

whose values are rooted firmly in the logic of the market

place. An acceptance that students are active in their

choice, consumption, and interpretation of global culture

should be balanced with recognition that these activities

are framed and limited by the logic and dynamics of

corporate capitalism. As Morley and Robins (1995) write, we

should not respond by "romanticizing the consumption

process and cheerfully celebrate the active viewer as a kind

of semiotic guerrilla, continuously waging war on the

structures of textual power" (p. 127).

A fifth principle is that teachers should see their

classrooms as crucial sites for discussing issues raised by

global culture. Schools provide an almost unique space in

which to develop in students a sense of critical distance.

Students may also begin to imagine alternative projects of

social existence. In the global market place, students are

discouraged from adopting critical distance by the seductive

power of imagery and the lack of opportunity to talk back.

Students do talk back as examples of cultural translations

show, but the opportunities are limited. Schools provide

dialogical environments where students can discuss with

adults the meaning of their experiences and begin to see

their experiences in wider cultural contexts. Schools are

among the few places that provide such opportunity and, to

the extent to which sites of global culture are sights

imbued with meaning, art educators have a responsibility to

be engaged in dialogue with their students about global

culture. Stockrocki's (2001) work with her

students on shopping malls, advertising, and consumerism in

general is exemplary. She has her students ask about what

they are drawn to themselves, and in this context they

discuss issues such as conspicuous consumption, the

gendering of advertisements, consumption patterns in

different countries, and the depletion of recourses.

Finally, as the examples above indicate, it is possible to

critique global culture. The proposition, derived from the

theory of cultural imperialism, that the agency required to

critique has been rendered impossible is clearly false. In

their everyday encounters with imported cultural goods

people everywhere are engaged in critique, albeit at an

unconscious or inarticulate level. The process of

indigenisation or cultural translations is evidence not only

of human agency but the extraordinarily diverse ways agency

can work. What teachers need to do is to make these

processes conscious and thus available to understanding and

critique.

Appadurai, A. (1990). Disjuncture and difference in

the global economy. In M. Featherstone (Ed.), Global

culture: Nationalism, globalisation and modernity (pp.

295-310). London: SAGE.

Dr Paul Duncum is a Lecturer in Visual Arts Curriculum,

Faculty of Education, University of Tasmania, Launceston

where he teachers pre-service primary generalist teachers

and secondary art specialists. A former graphic designer

and high school art and design teacher, he has delivered

many conference papers and has over 60 publications in

scholarly journals and books in Australia, North America,

and England. The areas of his research include children's

spontaneous drawing, critical theory and art education,

picture appraisal strategies, images of childhood, and

popular and global culture. Recently published is

Duncum, P., & Bracey, T. (Ed.), On knowing: Art and

visual culture, Canterbury University Press. In 1991,

he was awarded the Manual Barkan Award from the National

Art Education Association and he is a member of the

Council for Policy Studies in Art Education in the

United States.

|