Figure 2

The Process

Stage One

Selected schools

commit to a minimum three-year full school implementation

process. Teachers at each

grade level identify areas of the curriculum that would benefit

from additional creative, holistic teaching strategies. As a

result of this exploration a "big" theme often

evolves, example, grade one, "Myself and Others".

Teachers at each grade determine three art forms that will

support the areas of the curriculum they have identified.

"Where can I use creative support?" is a question

that teachers ask themselves individually and collectively.

Examples

Grade One

Theme: "Myself and Others"

| Curricular Connection |

Art Form |

| Term one: language

arts

| Storytelling |

| Term two: social

studies |

Global percussion |

| Term three:

numeracy |

Songwriting

|

Stage

Two

Artists are briefed and

interviewed. Criteria for this selection includes that the

artist:

- Is a practicing artist;

- Demonstrates an interest in

holistic education and integrated teaching/learning;

- Is willing to commit to the

collaborative curriculum development and implementation

process;

- Is willing to become familiar with

curriculum in the areas of math, science, social studies and

language arts;

- Is willing to make a long term

commitment (minimum of three years);

- Demonstrates interest and affinity

for children.

Successful candidates are added to

the roster of artist educators. Artists are divided into teams of

three artists per team (three different arts disciplines) to work

closely with individual schools and specific grades.

Stage

Three

Artist professional development

sessions are held to provide artists with tools in areas such

as the following:

- Provincial curriculum, age appropriate

material, classroom management, multiple intelligences, learning

styles, special needs, lesson planning, holistic education,

models of integration;

- Artists and teachers meet in their

respective teams to explore the theme, plan a sequence, research

content and begin to develop strategies for classroom

sessions;

- Individual artists meet with their

grade specific teacher teams and to collaboratively develop the

classroom units. Here teachers are lead through hands-on arts

processes to develop their skill set. Together specific

objectives and evaluation tools are developed.

Stage

Four

In the first term (late September

– December) over a 4-6 week period (which includes the

previously mentioned hands-on teacher workshop) the first artist

completes three classroom sessions (a minimum of one week between

sessions) with clear instructions for teacher follow-up and

extensions between visits. These sessions are considered on site

teacher professional development with ongoing dialogue encouraged

between sessions in person, by telephone, by fax, and by e-mail.

This ongoing dialogue also allows for integration and development

of the ideas the students bring to the creative process and to

the learning process. At the conclusion of the allotted three

classroom sessions the artist and teacher debrief. This process

is repeated in the second term with the second artist (the same

teachers and students). The process is repeated in the third term

with the third artist (the same teachers and students). A second

series of artist professional development sessions are held in

January offering additional topics to strengthen artists'

skill sets.

These four stages are repeated for

minimum of three years with the same artists and teachers

partnerships whenever possible. This allows teachers the

opportunity to deepen their skills from year to year while at the

same time providing students with a wide range of experiences as

they move from artist team to artist team in the three years. The

activities are documented and extended in Resource Guides that

are distributed to participating teachers and artists each year.

These Resource Guides become collections of "best

practices" to be shared by all participants.

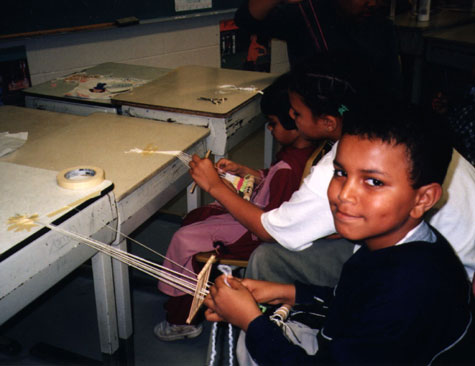

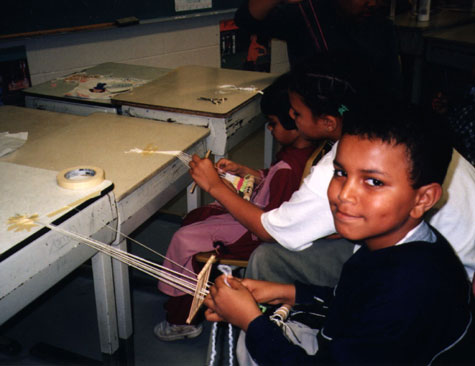

In-class artist

session, social studies through

storytelling

Examples of Best

Practices

This grade 5 unit was developed by

a dancer and the grade 5 teachers and focused

on the science curriculum,

Structures and Mechanisms. The three classroom sessions were

Building Bridges, Movement and Motion, and Systems in

Motion.

Session I: Building

Bridges

Preparation before the first

artist visit

The grade 5 students and the

classroom teacher were requested, by the artist, to research a

range of bridge structures, including the way location influences

design. They then identified the sequence of steps involved in

building a bridge.

In groups of 4-5, students used

their bodies to imitate the structure of a number of different

types of bridges. The students are guided by the dancer in

finding points of balance, stability and exploring concepts such

as stress, weight and truss.

Once secure, students were

challenged with a problem.

"You are a small private

business on the brink of bankruptcy. A giant corporation has

approached you to build a bridge. Winning the contract will

ensure your business success. You must prepare a presentation to

sell your bridge to a panel of judges. However, high winds and

uneven terrain plague the site of the bridge. You must take this

into account in your design and presentation."

Small group exploration (through

dance), design and presentation took place between artist visits,

facilitated by the classroom teacher.

Session II: Movement

and Motion

Preparation before the

second artist visit

The students and the classroom

teacher were encouraged to research gear systems, pulley systems,

axles and wheels. They then built simple prototypes of these ands

explored how they functioned independently and

together.

The prototypes and their function,

both individually and collectively, served as catalysts for

creative movement and contact dance. The students required a

clear understanding of the function of these systems in order to

apply the basic principles to dance. The students observed the

movement of their object and emulated the movement with their

bodies. They then used appropriate science vocabulary to describe

what was happening in the dance. This session concluded with

students committing to writing a report, using science

terminology, on the process of building their prototype and

imitating its movement. The report would be completed between

artist visits.

Session III: Systems

in Motion

Preparation before the third

artist visit

The students and the classroom

teacher were requested to research the concepts of structure,

mechanism, system, pressure, stability, torque and moving a heavy

load.

During the in-class session the

students explored different ways parts of the body can impose

force on other parts of the body (i.e. clasping hands softly as

opposed to loudly). They observed the mechanics of the arm as it

picks up a light object, a heavy object, and as it pulls someone

across the floor. To explore structure (a framework that is built

to sustain a load), students worked in pairs. One student acted

as the stable structure (in this case a table – two hands

and two knees on the ground) and the other student acted as the

load. By finding a point of balance the second student is able to

create a shape with his/her body on the back of the first student

(table). The first student (table) needs to understand principles

of stability in order to successfully carry the load (second

student).

To explore torque (the

product of force and the perpendicular distance to a turning

axis), the students rolled their bodies at different speeds. They

rolled on the floor lengthwise and then in tucked in position

– and observed what happens. In groups of twos and threes

they explored spinning and how the turning force changes when

more than one person takes part.

To explore the concept of moving a

load, the students were asked to problem solve how to move a

person from one side of the room to the other using two poles and

a large piece of plexi-glass or wood. The students soon

discovered that by placing the plexi-glass on the two poles and

having the person sit on top of the plexi-glass the person (load)

could be rolled across the floor. Once that concept was

internalized, students, in groups of 6-8, were given the same

challenge but without the two poles and the plexi-glass. The

teams of students worked together to create a mechanism – a

human conveyer belt. Several students lay lengthwise on the floor

side by side. Another student gently lay across the top of the

human conveyer belt and was transported across the

room.

Finally, students were asked

to use science vocabulary to write reports on mechanisms they

discovered and observed in their community. Where were they

found? How did they function? How could they be improved? The

students also had the opportunity to watch a contact dance

performance given by the artists with whom they worked. The

performance provided opportunities to experience the scientific

concepts performed as part of a production, thus deepening their

understanding.

Other samples of Best

Practices

Math and Social Studies

through Weaving

In this unit the students and

teachers worked with a weaver. Preliminary work involved

researching how the products of weaving were devoted to a single,

more complex set of activities. Students began by researching how

the products of weaving and fabric making are used in our

society. Next, students built a rigid-headle loom. They learned

to string it and weave on it. By compiling and assembling the

materials the students integrated concepts of math and problem

solving. The act of weaving itself required balancing several

variables: warp tension, shed alteration, the switching of the

weft or shuttle from hand to hand, and maintaining the correct

texture and pattern. Students acquired new vocabulary, learned to

plan ahead, and demonstrated an understanding of challenging new

concepts and skills. In follow-up sessions, students researched

the history of the fabric making and how fabric affects culture.

They wrote about the invention of the cotton gin and its impact

on slavery in North America.

Social Studies through

Visual Art (Sculpting)

This unit explored Asian history.

In groups of 4-5, students researched issues in Asian history.

They then created sculptures made of Asian materials (chop

sticks, rice bowls, bamboo, rice paper etc.). Upon completion

each group created a metaphor which best described their

sculpture. The sculpture pictured above was simply titled

"The Boat People". Another powerful sculpture was

entitled "The Sorrow over the Partition of

Korea".

Early Research

Early qualitative research

and testimonials (Elster, 1999, Wilkinson 1996, 1997, 1998)

demonstrate significant teacher growth over multiple years. The

data were gathered through surveys and ongoing teacher

evaluations completed by teachers participating in the initiative

over a three-year period (1995-1998). The teacher surveys were

distributed and collected at the end of the third year of

implementation. The surveys consisted of nine questions. The

first five questions requested teachers' views on their

classroom practice with respected to the arts before this

initiative. The remaining four questions invited teachers'

views on their use of the arts in daily classroom curriculum

since becoming involved in LTTA. Following the nine questions

there was space for additional comments with regard to their

views of arts and education in response to this

initiative.

The teacher evaluations

encouraged responses to the experience of working with artists

and the effectiveness of the initiative. The evaluations were

submitted three times a year, after each artist unit. At the end

of the second year, according to her principal, one first grade

teacher had developed more professionally than in her previous

twenty years of teaching (Wilkinson, 1996). At the end of the

third year teachers documented their changes in surveys which

contained the following comments (Elster, 1999).

Teacher testimonials indicating

change:

- Less fear of the arts

- More confident using the

arts

- Confident enough to attempt

current activities without the guidance of the artists

- Has made a concentrated effort to

use the arts daily in all areas of curriculum

- Regrets that this awareness was

not present at the beginning of the teaching career

- Has become an eager participant

and acknowledges reluctant start

- Takes every opportunity to do art with the

class

- Observes more teachers

(colleagues) are willing to take risks with the arts

- Is now more secure in the belief

that the arts teach creative thinking, problem

solving,

risk taking, team work and

communication

- Learned that risk taking in a new art form

can carry over to literacy, oral presentations and

can deepen the learning

experience of all students.

These same teachers also revealed

a greater understanding of the value of the arts, as documented

in the surveys (Elster, 1999):

- The arts reach a greater number of

students than other curricular areas

- The arts meet the needs of every

learning style

- Those who struggle at school and

those who have low attention spans excel in

the arts

- The arts can drive the

basics

- Children who seem

"hopeless" have come "shining through"

using arts as the motivator

- The power of art gives every child an

opportunity to be successful

- Results of research on positive effects of

LTTA on education in general.

The same group of teachers

documented the influence of the LTTA initiative (Elster,

1999):

- Appreciates the contributions of

professional artists can make to the learning and the aesthetic

growth of students

- Was an incredibly rewarding experience for

all

- It is an inspiration for the students and

the teachers to have an artist make a

presentation

- Observed students being engaged, motivated

and challenged to open their minds to creative thought

- Many students have hidden talents

who have not had the opportunity or exposure to new art

forms

- Saw the power of performance, how it

validated the students, calmed and focused

them (the students).

- Although this can sometimes be a

struggle we must continue

- (The arts education initiative) should be

adopted by the new Ontario curriculum

- Gave the teacher an opportunity to observe

students interacting with other adult teachers and to appreciate

their learning styles and changing values

- Really grateful for the experience

Teacher Development session;

Social Studies through Music

Is it

Successful?

LTTA is based on the premise that

in order for arts based education to be successful it must be

cumulative and sustained over several years. There is evidence

that programming that is brief, fragmented and infrequent has not

proven to be a successful approach to arts education (Korn,

1994). Consequently, the pilot project had a five-year time frame

based on our belief that sustained programming would have a

positive impact on the artists, teachers, schools and most

importantly, the students involved.

Already, there are indicators that

the program is taking hold of the minds and hearts of the

participants. In her review of journals kept by students in the

second year of the program, Dr. Joyce Wilkinson (1997), of The

Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, cited many links

between acquisition of English language skills and the arts. More

powerful is the evidence that suggests that Learning Through The

Artsäis successfully breaking through barriers that

have impeded the learning of many of the students involved. As

suggested by the Artsvision report, the infusion of arts into the

curriculum does indeed seem to engaging students, particularly

those with linguistic, cultural, emotional and behavioral

challenges. Evidence gleaned from student journals led to the

following statement by Dr. Wilkinson:

If Learning Through the Arts does

nothing more than help children and teenagers cope with the

emotional challenges they face, as it has already done for these

young people, it will surpass any expectations anyone could have

for its success. (Wilkinson, 1997, p.7)

Where Are We

Now?

Six years after initial discussion

began this initiative has completed the five-year pilot program

in 9 schools. By the end of the first five-year pilot program all

nine schools committed to continuing Learning through the

Artsäwith their own funding. These schools have

entered a second phase of implementation that empowers schools to

self manage. The former North York Board of Education (now the

Toronto District School Board) has contributed funds to allow 15

new school to participate. In 1999 with funding from the

Millennium Bureau of Canada and other sponsors LTTA began

implementation in Vancouver (Lower Mainland), Calgary, Regina,

Windsor, Cape Breton and Corner Brook. This national expansion

sees Learning Through the Artsä in 63 schools

with 20,000 students participating. With a second National

expansion launched in February 2001 that includes Niagara,

Ottawa, Thunder Bay, Winnipeg and Montreal LTTA is positioned to

expand to include 240 Canadian schools with 100,000 students

participating by 2003. It is a transferable model that meets the

unique needs of our rich and diverse national

landscape.

The process has not been without complex

challenges and certain risks. Every LTTA site has experienced

education changes, some more significant than others, including

amalgamation of Boards of Education, changes in political

climates, budget cutbacks, extreme teacher attrition and a move

towards "the basics". Schools

are facing heightened expectations for student achievement on the

part of both parents and business and community leaders. This

has led to the introduction of a more demanding and uniform

academic curriculum, and of standardized testing. The guiding principles of sustainability

and sequential building become difficult given these

circumstances.

Another significant

challenge is with regards to the limited time artists spend in

the classroom (a minimum of three, 1.5 hour sessions a year for

each of three artists). Ideally, potentially with additional

funding, a greater number of classroom visits will be possible.

In the interim, a combination of ongoing resource support and a

focus on what happens between sessions, when the artist

isn't in the classroom, helps balance the need for more

sessions with the artists.

Early results on the LTTA

national expansion based on research directed by Dr. Rena Upitis

and Dr. Katharine Smithrim shows that students who receive

education rich in the arts are more likely to read for pleasure,

more likely to perform well on mathematics and language tests,

and less likely to spend leisure time watching television and/or

playing video games. However, it is also the case that those

students most likely to be involved in arts activities are those

students who come from families where incomes are relatively high

and parents are well-educated (Upitis & Smithrim, 2001). A

detailed account of this research is presented in

Baseline Student Achievement and Teacher Data

from Six Canadian Sites. (Upitis & Smithrim,

2001)

An education system with the

arts at the core of it can offer the benefits of the arts to all

students. We are motivated to do so because we care. Carl Rogers

reminds us that the simple act of caring is a vehicle that

fosters creativity. "Caring is an attitude that is known to

foster creativity – a nurturing climate in which delicate,

tentative new thoughts and productive processes can

emerge." (Rogers, 1980, p.160)

The power of the arts, the

value of arts in education, the arts and the generalist, the

vulnerability of the arts, arts educators and artists in our

schools, the need for creativity in the arts and in our lives;

these issues have all been addressed. For me, one of the most

compelling responses to all of these issues is provided by Maxine

Greene. who presents us with the premise that art and imagination

should central in education:

We must make the arts central in

school curricula because encounters with the arts have a unique

power to release the imagination. Stories, poems, dance

performances, concerts, paintings, films, plays--all have the

potential to provide remarkable pleasure for those willing to

move out toward them and engage with them. (Greene, 1995,

p.27)

Where Do We Go From

Here?

Is it presumptuous to think that

the arts can transform school environments? Perhaps for some this

is the truth, but others indicate not (Lewis, 2000). In my work

across Canada, the USA and Europe I have the honour of meeting

many who care about education. A large number of these

individuals have compelling visions for change. Throughout most

of the discussions regarding change the conversation will move to

the obstacles that impede such change, with institutional

impediments often cited as insurmountable. In other words, no

matter how much hope the vision holds, feelings of fear and of

lack of support emerge as barriers to implementation. There is,

however, a counterpoint to institutional resistance and that is

"social movement" (Palmer, 1998). Despite the current

challenges facing the arts in education LTTA has moved forward at

an accelerated pace over the course of the past six years. Based

on our experience and research, we can identify several reasons

for the rapid growth:

- The sustained, sequential

structure;

- The building of authentic relationships

between artists and teachers;

- The focus on artist and teacher

development;

- Direct partnerships with Boards of

Education;

- The strong institutional support

from The Royal Conservatory of Music based on the belief that the

arts are a viable vehicle for social change.

It is this last reason that

compels me to believe that the institutional resistance that

impedes change can be balanced (if not eliminated) by an

imaginative initiative being supported by a major educational

institution. As an artist and an educator who has personally

experienced the frustration of holding a vision and not finding

the support necessary to bring this vision to life I am

personally filled with hope as we move forward with LTTA. I am

encouraged by the institutional support and the firm commitment

that The Royal Conservatory of Music, under the direction of the

President Dr. Peter Simon, continues to offer. All that had to

happen to initiate such major educational transformation was for

one institution to see the opportunity and to take it. By one

institution making a commitment the example has been set. Within

The Royal Conservatory of Music there was a critical mass driving

the change and now there is the foundation for a critical mass

being built across the nation – one school district at a

time. Our experience continues to renew our hope and offers

others the courage to hope.

Note

Presented at the

American Educational Research Association Annual Conference,

Seattle, Washington, April 10-14, 2001. The research reported

here was supported, in part, through the generous support

of the Millennium Bureau of

Canada, the Canadian Pacific Charitable Foundation, and the

George Cedric Metcalf Foundation.

References

Abbott, J. (1999). The child is

the father of the man. Hertfordshire, UK. The Bath

Press.

Barth, R. (1990). Improving

schools from within. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass

Inc.

Csikzentmihalyi, M.

(1996).Creativity: flow and the psychology of discovery and

invention. New York, NY: Harper Collins.

Drake, S. M. (1998). Creating

integrated curriculum: proven ways to increase student

learning. Thousand Oaks CA: Corwin Press.

Drake, S. M. (1993). Planning

integrated curriculum. Alexandria VA: Association for

Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Drake, S. M. (1992). Developing

an integrated curriculum using the story

model.

Toronto, ON: The Ontario Institute for

Studies in Education.

Dewey, J. (1934). Art as

experience. New York, NY: Putnam.

Eisler, R. (2000).

Tomorrow's Children. Boulder, CO: Westview

Press

Eisner, E, W. (1994). Cognition

and curriculum reconsidered. New York, NY: Teachers College

Press.

Eisner, E. W. (1985). The

educational imagination: on the design and evaluation school

programs (2nd ed.). New York, NY:

Macmillan.

Elster, A. (1999). The

reflective practitioner in search of a song: A study of teachers

in the LTTA program. Toronto, ON: Unpublished master's

thesis, The Ontario Institute of Studies in Education.

Elster, A. and Bell, N. (1999).

Learning through the arts; A partnership in educational

transformation. B Hanley (Ed.). Leadership, advocacy,

communication; a vision for arts education in Canada.

Victoria, BC: Canadian Music Educators Association.

Gardner, H. (1999).

Intelligence reframed, multiple intelligences for the

21st century. New York NY: Basic Books.

Gardner, H. (1993). Multiple

intelligences: The theory in practice. New York NY: Basic

Books.

Gardner, H. (1991). Art

education and human development Los Angeles, CA:

The Getty Center for

Education in the Arts.

Gardner, H. (1991). The

unschooled mind: How children think and how schools should

teach. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Gardner, H. (1983). Frames of

mind: the theory of multiple intelligences. New York, NY:

Basic Books.

Gardner, H. (1982). Art, mind

and brain. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Greene, M. (1995). Releasing

the imagination. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass

Inc.

Korn, M. (1994). An arts and

education needs and assessment of Metropolitan

Toronto. Toronto, ON: The Royal Conservatory of

Music.

Landsberg, M. (Dec. 13, 1997).

Book leads to musical epiphany, Toronto, ON:

"The Toronto

Star."

Lewis, S. (Nov. 10, 2000). How

can you call it education without the arts? Markham ON: Key

note address at the Arts summit, York Region Board of

Education.

Miller, J. (1994). The

contemplative practitioner. Toronto, ON: Ontario Institute

for Studies in Education.

Miller, J. (1990). Holistic

learning: A teacher's guide to integrated studies.

Toronto, ON: Ontario Institute for Studies in

Education.

Moore, T. (1992). Care of the

soul. New York, NY: HarperCollins.

Palmer, P. (1998). The courage

to teach. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Rogers, C. R. (1980). A way of

being. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Co.

Upitis, R. and Smithrim, K.

(2001).Learning through the arts, National assessment, a

report on year 1. Kingston, ON: unpublished manuscript,

available from Queens' University and the Royal

Conservatory of Music.

Upitis, R. and Smithrim, K.

(1998). Teacher development and elementary arts education. B.

Hanley (Ed.),Leadership, advocacy, communication: a vision for

arts education in Canada. Canadian Music Educators

Association.

Upitis, R. (1998). Pre-service and

in-service teacher education in the arts; Toward a national

agenda. B. Roberts (Ed.), Connect, combine, communicate:

Revitalizing the arts in Canadian schools. Sydney, NS:

University College of Cape Breton Press.

Wilkinson, J. A. (1998). Learning

through the arts assessment (interim report) Toronto, ON:

Unpublished manuscript, available from The Royal Conservatory of

Music.

Wilkinson, J. A. (1997). Learning

through the arts assessment (executive summary) Toronto, ON:

Unpublished manuscript, available from The Royal Conservatory of

Music.

Wilkinson, J. A. (1996). Learning

through the arts assessment (interim report) Toronto, ON:

Unpublished manuscript, available from The Royal Conservatory of

Music.

About the

Author

Angela Elster

The Royal Conservatory of

Music

Toronto, Ontario

Telephone: (416) 408-2824 ext.

223

Fax: (416) 408-3096

E-mail:

angelae@rcmusic.ca

Angela Elster is the

Executive Director for the Learning Through the

Arts Program, at The

Royal Conservatory of Music (Canada). She is a

musician by training,

and also teaches Orff music to young children. She is

a

PhD candidate at the

European Graduate School in Switzerland. Her

research interests

include teacher growth and the arts inspiring hope.

|