International Journal of Education & the Arts | |

Volume 3 Number 1 |

January 25, 2002 |

|

The Postmodern Artist in the School:

|

|

Partnership programs between artists, arts organizations, and schools is a means of bringing the arts into schools that is growing rapidly throughout North America. Through arts partnership programs, students and teachers interact with practicing artists and musicians, making connections with artistic communities and engaging in learning that is based in the artistic practices of arts communities. Although it is not unusual to hear general claims about the positive impact arts partnership programs have had on learning, little attention has been paid to the artists' perspectives of artistic practice and how this influences the nature of the educational experience. Further, although it is not uncommon to hear how artists have enriched arts education, there is very little discussion of artists' experiences in the school setting. Particularly absent is research addressing how artists adapt to the school environment and how working in the context of the school institution impacts the nature of their artistic practice. These are the central questions addressed in the present paper. In response to these gaps in the research literature, I review the basic tenets of modern and postmodern thought in the art world, and discuss how these two traditions of thought have shaped perspectives of artistic practice. To shed further light on this theoretical discussion, I reflect on my experience as a visual artist working from a postmodern perspective in an elementary school as part of an arts partnership program. Specifically, I discuss how in making art in the public space of a school institution I found myself censoring the content of my work, which ultimately resulted in a shift of the style and purpose of my art-making. Finally, by considering curriculum orientations that a school may enact and the values and philosophical assumptions that underpin them, along with the positions of the current postmodern art world, I discuss the complex position that the artist may occupy in the school while participating in an arts partnership program. From modern to postmodern perspectives of artistic practiceSince the Enlightenment, Western thinking has been firmly based upon a reductionist epistemology in which scientific models of inquiry have reigned in the pursuit of understanding reality. This scientific perspective of reducing reality to its essential components in order to gain insight into objective "truths" has given way to a postmodern view that emphasizes the social forces that shape human behavior and understanding and questions the possibility of absolute truths (Doll, 1993; Lyotard, 1984; Shiralli, 1999). The metanarratives of science and history that provided the infrastructure for our most exalted beliefs about truth, certainty, reality, and beauty have been deconstructed, revealing modernist epistemological absolutes as socially constructed. In a postmodern era, the modernist belief in epistemological absolutes has given way to a reliance upon "persuasive rhetoric, arguing from information rather than knowledge, and accepting that information is always provisional" (MacGregor as cited in Clark, 1996, p. 9). In the art world, modernist works of art emphasized the communication of essential truths through the purity of form. It is important here to distinguish between the term modern, which refers to Western humanist ideals that stem from the Cartesian thinking of the Enlightenment, and the term modernism, which refers to the period beginning in the late nineteenth century in which artists abandoned the premodern artistic conventions of idealistic realism in an attempt to represent visual essences (Schiralli, 1999). In rejecting past modes of expression, modernist artists pursued innovative visual styles by looking inward for creative inspiration. As a result, subjective self-expression, devoid of any social function, became the mainstay of modernist art. In the search for innovative visual representation, modernism resulted in an array of novel visual styles that required a new language for interpreting artistic expressions, and, consequently, formalism was adopted as the universal language of art (Clark, 1996). Formalism manifested a modern perspective in that it attempted, in a scientific manner, to breakdown the properties of form to its essential parts. Formalism, it was thought, represented a universal language of art that provided both the basis for expression and the perceptual context for viewing art. Postmodernism announces a shift from the modernist emphasis on works of art communicating essential truths through the purity of form to art as a cultural product which elicits multiple interpretations of meaning. In rejecting formalism, postmodern artists create art that challenges the modernist assumptions of formal relations, originality, and self-expression. Postmodern artists use narrative, allegory, metaphor, and juxtaposition of different images, to deal with content such as social and political issues, art as a consumerist product, and art as a critique of society and culture (Wolcott, 1996). Where the modernist artwork was thought to embody the artwork's meaning, postmodernist artwork demands an interpretation that encompasses the broader cultural context. While a modernist perspective relied on Western Eurocentric conceptions of art and the critic's judgement of an artwork's meaning, a postmodern perspective seeks a plurality of perspectives and multiple interpretations of meaning. Artists working from a postmodern perspective often produce work that comments on the narrow conceptions of the modernist art world and the dominant perspectives that it supported. Postmodernist works of art deconstruct modernist aesthetics of form, revealing the socially constructed nature of visual representation and judgements of artistic value. From Modern to Postmodern approaches to art educationMany school art programs still emphasize modernist conceptions of art and, as a result, children engage in school art activities that promote a conception of art and art-making that bears little resemblance to that of the postmodern contemporary art world (Clark, 1996; Duncum, 1999; Efland, 1990; Pearse, 1992). As Clark states "[t]he long reign of modernism lulled teachers into a state of artistic complacency; for decades they could keep abreast of the developments in the art world simply by familiarizing themselves with the latest -ism popular with the avant-garde elite" (p. 65). Although art curricula in elementary schools by and large remains entrenched in modernist conceptions of art (Wolcott, 1996) many art educators recognize the urgent need to re-evaluate art education in light of the issues raised by postmodern thought and practice. Consequent to the diversityof issues raised and the complex nature of postmodern theory, theoretical responses to postmodernism in art education have necessarily been diverse. However, in Art Education: Issues in Postmodern Pedagogy, Clark (1996) states that responses to postmodernism can generally be seen as representing one of two perspectives, the reformist or the reconstructionist. Notwithstanding, in practice art educators enact a diversity of approaches to art education that represent a blend of influences which do not fit neatly into one of these two positions. However, these two perspectives provide a useful framework for understanding two general streams of influence that characterize the current climate in the field. According to Clark (1996) "[r]eformers believe that traditional models of art education are resilient enough to retain traditional Western art forms and practices while embracing culturally pluralistic exemplars and concepts" (p.73). However, reformist approaches, such as discipline-based art education (DBAE), often advocate essentialist models of art education that favor interpretation methods derived from modernist aesthetics (Pearse, 1992). In an attempt to legitimize the arts academically, DBAE presents a curriculum based in the in the "disciplines" of studio art, art history, aesthetics, and art criticism that is testable, sequential, and accountable (Pearse, 1992). These characteristics reflect scientific rationalist thinking characteristic of a modern perspective of education. If we are truly to move to a postmodern orientation we cannot simply "add on" examples of art and art-making, as the above reformist statement implies, to a modernist curriculum based in Eurocentric Western traditions. Further, postmodern art does not lend itself to modernist aesthetic modes of interpretation that emphasize the formal aspects of artworks. Unlike modern art, where the focus was on formalistic concerns, postmodern art emphasizes sociocultural contexts using images as reference points for the construction of meaning. Therefore, a postmodern approach to art education should acknowledge the sociocultural contexts that influence and shape our notions of art and art-making, and the need to move beyond modernist aesthetics that are historically bound in Western conceptions of fine art. The reconstructionist perspective, the second position that Clark (1996) characterizes, is founded on the notion that art education is a means for social transformation through the critical analysis of social values that are inherent in works of art. Reconstructionists aim to provide students with the critical skills needed to analyze the hegemonic power structures that limit personal potential, as well as the structures in which they participate that restrict the potential of other social groups (Grant & Sleeter, 1989). In this way, reconstructionists believe that art education should shift from a subject area to become a pedagogical tool that can be used across the school curriculum for the purpose of critical analysis, and ultimately, social reconstruction (Freedman, 1994). An approach to art education that emphasizes the transformation of beliefs and values through a sociocultural contextual analysis of visual images should employ a diversity of images, past and present. In educating students from a variety of perspectives of the human experience, a postmodern approach to art education emphasizes the importance of employing images that represent those voices traditionally marginalized in the art world, such as those of ethnic minorities and women. This is of critical importance. However, this is often misinterpreted as a need to leave the Western canons of art behind as they only represent the work and dominance of the white male artist. In order to teach students about the social and political forces that shape our conceptions of art and art-making, art education should include those works that are sometimes categorized as representing the dominance of the white male artist and the authority of the "high" art world. Transforming art education through arts partnership programsSince modern ideology pervades our social-cultural institutions and individual values and beliefs at many levels, shifting to a postmodern perspective is a formidable task. One means of bringing a postmodern perspective of artistic practice to art education in schools is through the introduction of arts partnership programs with reconstructionist commitments. Arts partnership programs with such commitments may offer a way of narrowing the contextual gap that exists between contemporary art theory and practice of the art world and school based art theory and practice. As Sullivan (1993) states "To get a realistic perspective on what is authentic practice there is a need to cast a net beyond the classroom to incorporate the wider realm of professional art and the local context of everyday experiences" (p. 16). "Authentic" learning experiences are those which resemble "real life" practices and encourage learners to engage in the processes of practitioners. The value of such learning experiences is supported by research demonstrating that when learners are provided with authentic learning situations, meaningful learning occurs (Brown, Collins, & Duguid, 1989; Cobb & Bowers, 1999; Lave, 1997; Lave & Wenger, 1991). Teaching through authentic activities complements other educational methods by providing learners with opportunities to access practitioner knowledge and skills, and to gain an understanding of the contextual influences that shape artistic practices. The artist should not be viewed as modeling artistic practice in general, but rather as providing an in-depth account of a single perspective of artistic practice. By experiencing the work of a practicing artist students may gain a better understanding of how artistic practice is actualized within the cultural context of a contemporary artistic community. However, when implementing arts partnership programs it is important to consider the positions from which participating artists work as these have immediate consequences for the type of learning that will take place. If partnership programs are to connect schools with the artistic practices of art world, it is paramount that artists who work from a postmodern perspective of art participate in these programs. By bringing postmodern artists into the schools it may be possible to challenge the modernist status quo approach to art education that is dominant in art education programs today. An artist who works from a postmodern perspective of art may challenge students to question their assumptions about the function of art in society by engaging them in new ways of looking at art and the many roles that art can play in society. By sharing postmodern works with students, and encouraging a postmodern mode of interpretation that acknowledges the subjective and sociocultural contexts that shape interpretation, students can be exposed to new ways of making meaning from their encounters with art. Although I believe that it is critical that we bring artists into the schools who challenge status quo conceptions of art education, my experience in the school revealed the complexity of working from a postmodern perspective within the context of a school that enacted a curriculum approach that, by and large, represented a transmission approach to learning and modernist conceptions of art education. My experience as an artist in a schoolI participated in an artist-in-residence program that took place in an elementary school as part of a larger arts development initiative called Teachers As Artists (TAA) (Upitis, Smithrim, & Soren, 1999). The TAA program was designed to engage elementary teachers in rich arts experiences with the aim of increasing their artistic and creative sensibilities and ultimately, increasing the presence of the arts in their classrooms. The entire school staff, including the Principal and educational assistants, took part in after school workshops led by community artists exploring different media and art forms. It is important to note that the purpose of these artist-led workshops was not to teach teachers how to teach the arts, but rather to provide teachers with opportunities to explore their artistic selves. The goal of the four year research project was to help teachers become artists, and then to document and support the subsequent infusion of art into the school community. In addition to the artist-led workshops, an artist-in-residence program was implemented each year of the program. The artist-in-residence component of the program was loosely defined, as the TAA program was in the early stages of developing the structure and implementation procedures for this aspect of the program, and, as such, there were few guidelines for artists-in-residence. It was ultimately up to each artist to design and implement a program in such a way that they produced work in the school and interacted with students and teachers. The primary purpose of these programs was to expose students and teachers to artistic practices by having community artists establish studio spaces in the school. As one of the initial artists-in-residence to participate in this program I did not have the experience of previous artists to aid me in the logistics of implementing such a program. With no guidelines to follow, and only a basic program goal in mind—to set up a studio in the school, and by doing so, provide an educational experience for the school community—I entered the school with uncertainty. Once tentatively settled in my school studio, I proceeded to work on mixed-media pieces that I had started prior to serving in the role of artist-in-residence. These pieces were made from paper, earth, gauze, beeswax, and other natural materials and focussed on the theme of domestic processes traditionally associated with women and the binding stereotypes that are attached to them. As part of the art-making process I engaged in a routine of sewing natural fibers together using a disorderly stitch that resulted in clothes-like garments.

Margaret Meban. Untitled installation (1997) This process had a cathartic quality as I eschewed concerns of neatness, cleanliness, and order engaging in an intuitive process where I focussed on the aesthetic qualities of the natural materials. The clothes-like garments that resulted from this process were then washed in a basin of earth and water and hung on the walls of the studio to dry like laundry on a clothesline. In these works I integrated fragmented associations and juxtapositions such as dirt/earth, women/earth, and purity/cleanliness which resulted in an indeterminate dialogue that is ambiguous yet familiar. Engaging in processes traditionally associated with women—sewing and washing—in an unorthodox manner, these works comment on stereotypic ideas about women's sensibilities that are tied to domestic processes. Integrating ancient symbols into these works, I wanted to impress the idea of how a stereotype may become a symbol in our unconscious that is difficult to consciously alter. I found this work rewarding as it revealed how both rejection and adoption of stereotypes has influenced my identity as a western, white, middleclass woman. By addressing issues of women's identity through an exploration of domestic processes and the socially constructed stereotypes that are connected with such processes, and by employing visual forms that do not adhere to modernist models of aesthetic value, this work embodied a postmodern view of art.

During the first few days in the studio the occasional curious student would come into the studio to see what I was doing, and then as word got around, a steady flow of students came into the studio to see me and my work. I could sense from both teachers and students there was a slight hesitation in articulating their feelings towards my work. “What's that?” students would say with crunched up faces pointing to one of the mixed-media earth pieces. It became apparent that the majority of students did not understand or have the conceptual tools to access the imagery I was creating. There was however a small group of students and a couple of teachers who came in and responded positively to the work, showing a keen curiosity in the different materials. Working in a space where individuals could come in and ask questions about work in progress was difficult to adjust to, as I felt I had to explain or justify each step of my art-making process. Initially I thought this was a good experience as it forced me to examine and clarify my objectives as an artist. But in the long run, I found this process to be disruptive because it halted the free-flowing nature of my process and forced me out of ambiguity. When I had to stop and explain at various points of the process, I lost momentum. In contrast, my private studio experiences are times of quiet introspection where I can give complete attention to the production of images. Self-censorshipWithin the context described above I presented an introductory slide show to each of the 7 classes (Grades 1-8). I thought this would give me an opportunity to discuss my work and experiences as an artist. However, as I began to discuss some of my work with the first few classes that visited the studio it became clear that my audience of students and teachers were viewing the work through a lens that attended to formalistic attributes of the work. As I went through the slides, those works that demanded a reading that went beyond the formal elements of composition were met with very little response or silence. Even with my comments about the themes and personal experiences that initiated the works I felt that there was a lack of understanding of my work. One teacher even laughed and asked "what is that, an alien?" when a slide was shown of a mixed-media piece that was composed of hair, mud, and material in a dress-like form. These reactions made me realize that in order to access this type of work, one has to be informed about art from a postmodernist stance. Further, three of the pieces included in this slide show were works I had produced while being surrounded by Catholicism in Italy. Although this triptych of crosses did not give direct detail or access to the thoughts behind the images, such as my feelings about some of the negative influence of the Catholic church, it would have been inappropriate to discuss these images in a Catholic school. As a result, I was perplexed as to how to proceed in my role as artist-in-residence as I recognized the need for an in-depth examination of modes of interpreting art that would allow students to re-orient their means of understanding artistic production to those more compatible with postmodern interpretation, while at the same time, recognized that this was a systemic issue that could not be rectified through one artist's visit. As Bumgarner (1994) states in conclusion to her extensive study of the National Endowment's artist-in-residence program, “To expect professional artists to inculcate teachers and school administration with a conception of arts education so vastly different from prevailing practice is illogical and unrealistic” (p. 11). After this general introduction to the school community I began to think of themes for the new series of work I was to produce in the school studio. At this point in my residency I already felt that I was censoring my ideas searching for school "appropriate" imagery and themes that would be acceptable within the context of this school. The school atmosphere was influencing my work even though I had made a conscious effort to make this art-making experience as authentic as possible, by approaching my art-making in the same manner I had in previous studio experiences. My past work did not contain obvious imagery that would need to be censored for viewing by young children, but my initial interactions with teachers and students led me to believe that the themes and issues reflected in certain pieces would not be well received within the context of this school. So, although my work would not be considered controversial within the art world, I felt that this school had certain ideals and agendas that would not be receptive to the themes in my work. This self-censorship ultimately caused a shift to “safer” work both for me and the students—for me focussing on the technical skills of rendering images rather than addressing personal experience or sociocultural issues, and for students in that they could easily read the images and no controversial themes would be in play. Student InterestCoupled with my concern about the content of my work, students keen interest in depicting figures and animals in a realistic style also influenced the nature of my role in the school. Although I encouraged students to explore themes important to them and to use materials that enhanced the meaning of their works, students were keenly interested in producing realistic renderings based on wildlife themes. On the one hand, I felt that by teaching students about the formal and technical elements of art-making I was addressing the interests of the students. They were motivated and dedicated to their work, and in the end, an artist needs some painting and drawing skills to be able to depict their thoughts in a visual form.

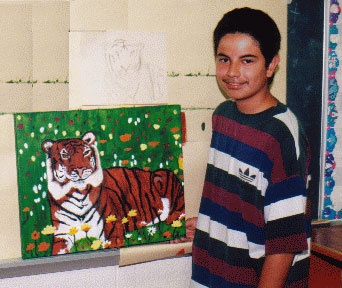

Grade 8 student working on an acrylic painting On the other hand, I wondered how "school art" had influenced these students conceptions of art and art-making—merely creating images for the purpose of being aesthetically pleasing with no consideration of social function. Was the students' interest a socially constructed response to the school institution's perception of art? Or was the students' interest in depicting a photographic likeness a developmental stage in artistic development as the proponents of the U-curve theory (Davis & Gardner, 1993; Gardner & Winner, 1982) would suggest? In other words, was I addressing the interests and developmental needs of the students or was I inadvertently supporting the interest of the school institution? Or both? As I was confused about the nature of my pedagogical role in this situation, I began to address students' immediate interests by demonstrating drawing and painting skills by depicting images of animals, figures, and landscapes.

A process of enculturationMy experience as an artist-in-residence reveals a process of enculturation whereby the school's values gradually took precedence over my values as an artist. Working in a public space that was not receptive to my initial work, coupled with confusion as to the educational role I was to fulfil in this school, resulted in a shift in the purpose and style of my work. By participating in this artist-in-residence program I was to establish a studio space in the school and to create an environment where students could come in and view an artist working and ask questions about the work and process. However, the more I became encultured into the school institution, the more I assumed the accompanying roles of that domain which included choosing school "appropriate" themes and imagery. In changing the style of my work to suit the school audience I produced work which conformed to a particular conception of what art is—images rendered in a realistic style whose primary purpose is to depict photographic likeness of reality. Consequently, I didn't feel I was truly sharing my “artist” self or broadening the boundaries of art for the school audience. Curriculum approaches: Implications for arts partnershipsMy experience as an artist-in-residence revealed that arts partnerships are considerably more complex than one would first imagine. Partnerships involve the coming together of two distinct social institutions, the school and the art world, which have traditionally been considered to play quite dissimilar roles in society: the role of schooling is to reproduce the status quo whereas the artist is thought to be one who pushes the boundaries challenging the status quo.  Artist-in-residence Margaret Meban working on a mixed-media piece Ryan and Shreyar (1996) suggest that by viewing schools through a cultural framework it may be possible to rethink how we conceive, implement, and analyze arts partnerships. While acknowledging that a school's culture is comprised of a diversity of cultures working simultaneously together, Ryan and Shreyar suggest that an investigation of the overarching curriculum approaches used by schools is one possible means for analyzing the beliefs and values that underlie a school's practices. A school's curriculum embodies particular values about the purpose of education and philosophical assumptions as to what knowledge is most valuable for students. These values and philosophical assumptions are then translated into the various aspects of the educational process such as specified educational outcomes, methods of teaching, and student and teacher roles. Moreover, cultural artifacts, such as texts, assessment tools, projects, performances, and artworks, reflect the purpose of a school's culture and the knowledge it values. Curriculum perspectivesFollowing Jungck and Marshall (1992), Ryan and Shreyar (1996) provide a framework that synthesizes the wide variety of curriculum approaches that have been proposed by curriculum theorists over the past several decades into three generalized orientations: transmission, transaction and transformation. A transmission orientation to curriculum maintains that there is an essential body of predetermined knowledge that students must ingest in order to adapt and fulfil a position within the existing societal structure. The teacher's role is to transmit predetermined knowledge and skills to students as efficiently as possible through teacher directed instruction, and to assess learning by the degree to which children's products represent the information they have been given. Social reproduction and social efficiency underlie this paradigm of curriculum in that the ultimate goal is to reproduce thestatus quo by replicating existing sociocultural values and beliefs through a mechanistic educational process. Unlike the transmission orientation, a transaction approach to curriculum acknowledges that knowledge is socially constructed within the context of experience. John Dewey (1963/1938) a leading proponent of the transaction approach, viewed knowledge as socially constructed and continually evolving as the learner's belief system is transformed through transactions with the physical and social environment and by reflecting on past experiences. Within this paradigm the purpose of education is to engage students in learning that enables them to participate in the reconstruction of themselves and society. The educator is a facilitator who creates learning environments where children's previous experiences, interests, and developmental needs guide the education process. A successful learning experience from a transaction point of view is one that recontextualizes students' systems of belief enhancing their understanding of the world. The epistemological perspective of a transformation approach to education is similar to that of the transactional approach in that knowledge is seen as socially constructed. However, a transformative orientation places more emphasis on the reciprocity between thought and action and the ability of the learner to actively address social and political inequities that exist within society. As societal institutions, schools are viewed as active agents for social change. Educators encourage students to think critically about the implications of knowledge claims and to consider how, why, and by whom knowledge is constructed. Here the aim of education is to raise students' critical conscious by providing them with the critical skills needed to analyze the hegemonic power structures that limit personal potential, and the structures that they participate in which restrict the potential of others (Grant & Sleeter, 1989). A transformation approach is education for social action in that it encourages students to become social activists challenging the status quo that maintains the inequities in the world. As Friere states, education for critical consciousness is "learning to perceive social, political, economic contradictions and to take action against the oppressive elements of reality" (Friere, 1994, p. 17). While acknowledging that most school cultures do not follow a curriculum that conforms neatly with one of these approaches, Ryan and Shreyar (1996) propose these curriculum perspectives as a way to think about the interactions that occur between a school's culture and the visiting artist's culture in arts partnership programs. From their experiences investigating arts partnerships, they perceived that the tension that arose between schools and artists was largely due to the different values and philosophical assumptions that underpinned the different cultures. The artists tended to adopt a transactional or transformational perspective of education while most of the schools subscribed to a transmission approach. Reflecting on my experience as an artist-in-residence through the lens of this curriculum framework provides some explanation for the tensions I felt in the school that ultimately led to a process of self-censorship. The values and philosophical perspectives that I address in my artwork are representative of a reconstructive postmodern perspective of artistic practice. Through producing work that explores the relationship between patriarchal power structures and my identity as a woman I unveil some of the hegemonic beliefs that have shaped experiences in my life. I wouldn't say that this work overtly precipitates social action; however, bringing these thoughts to the surface through art is a way of raising consciousness of these issues, which ultimately, influences social actions. In this way, the feminist and identity issues that I explore in my art work would fit into a transformative perspective of curriculum. The school in which I participated as an artist-in-residence subscribed, for the most part, to a transmission orientation to education. Although many of the teachers who participated in the Teachers As Artists program began to explore the arts and artistic ways of learning and understanding, they still, by and large, subscribed to a traditional teacher-centered approach to education. Working under the pressures of a conservative government which has precipitated a back to basics movement and the use of standardized tests as measures of success, the teachers at this school felt compelled to adopt a transmission approach to education to meet the current provincial curriculum standards. The teachers felt that the demands of the curriculum left little time for exploring alternative ways of understanding and being through the arts. The perspective of art that prevailed within this school epitomized a school art style (Efland, 1974) and did not show any evidence of a postmodern influence. The artwork that was displayed on bulletin boards and classroom walls was typical of elementary school art in that it generally represented holiday themes, repetitive patterns, and compositions constructed from materials such as tissue paper, construction paper, and tempera paint. Efland claimed that this typical school art style reflects the latent socialization agenda of the school rather than the interests of children. "The presence of the school art style can be explained as a result of the conflicts that arise between a rhetoric articulating the manifest functions [of art education] and the latent functions [of art education] which go unstated" (p. 40). Efland suggested that if a school's latent functions are of a repressive nature the manifest functions of a school's art program, such as becoming more human through art, are subverted by this latent socialization agenda and as the repression increases "art comes to be regarded as 'time off for good behavior' or as 'therapy'" (p.40). Further, in reference to the work of Illich (1971) and Gintis (1973) Efland noted that although education appears to have a democratic mandate, some authors believe that in actuality it often reflects a socialization agenda that more closely resembles the hierarchic structure of the modern corporation suggesting that this type of school art is repressive in that it encourages individuals to accept authority, follow orders, and participate in repetitive pattern making. In this way children will be more likely to accept the authority of the power structures of the outside world. To disguise the repressive socialization agenda of schools Efland suggests that another function of the school art style is to encourage behaviors and products that reflect humanistic learning by engaging students in expression with a predetermined range. Teachers encourage abstract, freeform scribbles that have a "creative look" while discouraging any form that steps outside of this artificial creative look. In this way school art manifests a modernist approach to art in that it emphasizes individual creative expression ignoring the social forces that shape the style and purpose of these productions. My awareness of the school's modernist status quo approach to the arts, coupled with the process of enculturation that I went through in the school, resulted in a process of self-censorship that ultimately caused a shift in the style and purpose of my work to accommodate the school's current structure of beliefs and values regarding art. Therefore, not only was I not producing the type of work that I would normally engage in, I was not engaging students in transformative experiences that would allow them to appreciate the values and beliefs of the contemporary world of postmodern artistic practice. Challenging the status quoBy questioning some of society's exaltedly held beliefs and values, and bringing to viewers attention the hegemonic power structures that circumscribe and perpetuate a certain way of being and understanding, postmodern artists challenge the status quo. Conversely, a school may enact an approach to curriculum that generally tries to promote values that represent the status quo, disregarding values that challenge the status quo. Within this implicit contradiction, how does the artist, who's intention is to critique socio-cultural values, work within a school? Perspectives and goals that conflict with those of the school are not likely be welcomed into the community. This conundrum that the artist may face within the context of the school is representative of the relationship the art world holds with other societal institutions. The art world is often falsely perceived as a realm outside of the confines of mainstream society where artists are free to express themselves in whatever way they choose in the name of art. However, the art world too is subject to social control by social institutions. The hierarchical power structures of government, economy, and religion all influence the art world through censoring what is acceptable within the confines of dominant sociocultural values and determining funding structures and standards that ultimately affect what art is supported (Lankford, 1990). In describing the contradictory nature of artistic freedom Lankford (1990) stated: Artistic freedom is a paradoxical aspect of the art world. In order to provide an environment that fosters maximum latitude and protection for artistic choices, the art world must sustain a positive, nurturing relationship with other segments of society. By creating opportunities for free expression, however, the art world opens itself to the possibility that what is expressed will go against the grain of predominant social norms and mores. By encouraging and defending such controversial work, it risks losing ground in its societal relationships, hence, it slips in its ability to guarantee freedom of expression. (p. 24) Therefore, the art world holds a precarious position in society in that its existence is dependent on maintaining relationships with other societal institutions, while at the same time, it tries to maintain its integrity as a social institution that challenges the status quo by providing a forum where individuals can voice positions that oppose mainstream values. Even the art world itself plays a significant role in perpetuating certain views of art and artistic practices (Lankford, 1990). Members of the art world, such as critics, curators, gallery directors, and artists, play a critical role in shaping perspectives of art and deciding what art will be supported and esteemed. Therefore, as Lankford points out the notion of artistic freedom is paradoxical when the confines of societal institutions, including the art world, are taken into consideration. My acts of self-censorship while working as an artist in the school reflected the contradictory relationship that artists hold with other societal institutions in general. As an artist working under the patronage of a social institution, I felt the pressure to adapt to the values of the school, while at the same time, realized that many of these values conflicted with my intentions as an artist. ConclusionsMy experiences as an artist-in-residence reveals some of the complexities that are involved in creating an educational partnership involving an artist's culture and a school's culture. Although my experience as an artist-in-residence illustrates how working under the patronage of a school institution resulted in a tension that caused me to accede to the dominant school culture, I still believe that arts partnership programs are a possible means of developing students' artistic understanding and complimenting a school's arts curriculum. However, as highlighted in the present paper, there are several critical issues that must be considered when implementing an artist-in-residence program. First, the purposes and educational objectives of an arts partnership program must clearly articulated prior to implementation (Bumgarner, 1994; Eisner, 1974). A program that does not have clear guidelines for artists and teachers leaves too much to be resolved through trial and error, and may jeopardize the educational success of a program (Remer, 1996). Substantial program planning, that includes the consideration of potential conflicts of interest that may arise between the artist's and the school's individual agendas, must be done prior to introducing an artist into a school. Had the program I participated in been so-planned, and a forum created where I and members of the school community could voice concerns, needs, and educational objectives prior to implementing the program, some of the tensions I faced as an artist in the school might have been alleviated. Further, in addition to considering the particular approaches to arts curriculum that a school may employ, it is also critical that administrators, teachers, and artists consider the approach a particular partnership program will take. This partnership can also be considered within the transmission, transactional, and transformative framework (Remer, 1996). The residency program that I participated in, by and large, employed a transmission approach to implementing a partnership program: the artist was to set up his or her practice within the school by establishing a studio setting for students and teachers with minimal input from teachers. This ultimately jeopardized the depth of “partnership” in this program. In order for an artist-in-residence program to move beyond a transmission type of partnership to become possibly a transformational experience, teachers must be encouraged to be participants at every level of the partnership program. As Bumgarner (1994) states, if an artist-in-residence program is to enhance a school's arts curriculum, “teachers must be actively involved from the residency's' conception through its completion and evaluation” (p. 19). Finally, although artists working from a postmodern reconstructionist stance may find working in the school a challenge, it is of critical importance that their voices be heard in the schools, as they may be able to encourage students and teachers to see and understand in ways that challenge modernist epistemological perspectives. Bringing a postmodern artist into schools through arts partnership programs is a possible way of bringing new ways of seeing and understanding that challenge, not only modernist conceptions of art, but of knowledge in general. By examining the modernist beliefs that may exist in schools through a sociocultural analysis of the modernist perspective, students can be encouraged to reflect on how their perceptions of art, and ultimately, their perceptions of the world have been influenced by modernist ideology that emphasizes the notion of essential truths and the universality of experience. Although this artist-in-residence program provided several opportunities where students and teachers alike gained skills and confidence in the arts, I do not believe that the program reached its transformational potential. If arts partnership programs are to promote their programs by advocating the socially transformative potential of arts experiences, such programs must consider the nature of the artistic practices that the artist brings to the school. If we want to challenge status quo art education and modern conceptions of knowledge, by engaging students in the critical practices of postmodern artistic production, programs must bring artists into the schools who work from a reconstructionist perspective and are who are willing to participate in the challenge of bringing such a perspective to schools. AcknowledgementsI wish to thank Martin Schiralli, Rena Upitis, and Ann Patteson for their comments on earlier drafts of this paper. Notes

ReferencesBumgarner, C. M. (1994). Artists in the classrooms: The impact and consequences of the National Endowment for the Arts' artist residency program on K-12 arts education. Arts Education Policy Review, 95(3), 14-30. Clark, R. (1996). Art education: Issues in postmodernist pedagogy. Reston, VA: National Art Education Association. Cobb, P., & Bowers, J. (1999). Cognitive and situated learning perspectives in theory and practice. Educational Researcher, 29(4), 11-13. Davis, J. & Gardner, H. (1993). The arts and early childhood education: A cognitive developmental portrait of the young child as artist. In B. Spodek (Ed.) Handbook of research in early childhood education. (2nd ed.) New York: Macmillan. Doll, W. E. Jr. (1993). A Post-Modern Perspective on Curriculum. Advances in Contemporary Educational Thought (Vol. 9). New York, NY: Teachers College Press. Duncum, P. (1999). A case for an art education of everyday aesthetic experiences. Studies in Art Education, 40(4), 295-310. Efland, A. (1974). The school art style: A functional analysis. Studies in Art Education, 17(2), 37-44. Efland, A. (1990). A history of art education: Intellectual and social currents in teaching the visual arts. New York, NY: Teachers College Press. Eisner, E. W. (1974). Is the artists-in-the-schools program effective? Art Education, 27(2), 19-23. Freedman, K. (1994). Interpreting gender and visual culture in art classrooms. Studies in Art Education, 35(3), 157-170. Friere, P. (1994). Pedagogy of the oppressed. NY: Continuum. Gardner, H. & Winner, E. (1982). First intimations of artistry. In S. Strauss (Ed.) U-shaped development. New York: Academic Press. Gintis, H. Toward a political economy of education: A radical critique of Ivan Illich's Deschooling Society. In A. Gartner, C. Greer & F. Riessman (Eds.), After Deschooling, What? New York: Harper & Row, 1973. Grant, C., & Sleeter, C. (1989). Race, class, gender, exceptionality and education reform. Pp. 49-65 in J. A. Banks & C. A. McGee Banks (Eds.), Multicultural education: Issues and perspectives. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon. Illich, I. Deschooling society. New York: Harper & Row, 1971. Jungck, S. & Marshall, J. D. (1992). Curricular perspectives on one great debate. Pp. 93-102 in S. Kessler & B. B. Swadener (Eds.), Reconceptualizing the early childhood curriculum: Beginning the dialogue. NY: Teachers College Press. Lankford, E. L. (1990). Artistic freedom: An art world paradox. Journal of Aesthetic Education, 24(3), 15-28. Lave, J. (1997). The culture of acquisition and the practice of understanding. Pp. 17-35 in D. Kirshner & J. A. Whitson (Eds.), Situated Cognition: Social, semiotic, and psychological perspectives. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Lyotard, J. F. (1984). The postmodern condition: A report on knowledge. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press. Pearse, H. (1992). Beyond Paradigms: Art Education Theory and Practice in a Postparadigmatic World. Studies in Art Education, 33(4), 244-252. Remer, J. (1996). Beyond enrichment: Building effective arts partnerships with schools and your community. New York, NY: American Council for the Arts. Ryan, S. & Shreyar, S. (1996). Arts partnerships in the classroom: Some cultural considerations. Pp. 346-355 in J. Remer (Ed.), Beyond enrichment: Building effective arts partnerships with schools and your community. New York: American Council for the Arts. Schiralli, M. (1999). Constructive Postmodernism: Toward Renewal in Cultural and Literary Studies. Westport, CT: Bergin and Garvey. Sullivan, G. (1993). Art-based art education: Learning that is meaningful, authentic, critical and pluralist. Studies in Art Education, 35(1), 5-21. Upitis, R., Smithrim, K. & Soren, B. J. (1999). When teachers become musicians and artists: Teacher transformation and professional development. Music Education Research, 1(1), 23-35. Wolcott, A. (1996). Is what you see what you get? A postmodern approach to understanding works of art. Studies in Art Education, 37(2), 69-79. About the AuthorMargaret MebanPh. D. Candidate Graduate Studies and Research Faculty of Education Duncan McArthur Hall Queen's University Kingston, Ontario Canada K7L-3N6 Telephone: (613)

545-9138 |