International Journal of Education & the Arts | |

Volume 3 Number 4 |

September 10, 2002 |

The Shadows of New

York:

|

Introduction

We enter upon a stage which we did not design and we find ourselves part of an action that was not of our making. Each of us being a main character in his [her] own drama plays subordinate parts in the dramas of others, and each drama constrains the others (MacIntyre, 1984, p.199) On September 11, 2001, American citizens awoke, literally and figuratively, to find themselves and their nation a part of a world drama that was not of their personal making—an international scene that not only constrained actions but flattened buildings, destroyed businesses, imploded airplanes, and extinguished lives. In short, the American way of life was brutally assaulted as a new kind of war waged not abroad, but on the home front. When tragedies such as the September 11th event strike, how can sense be made of actions that, in a multitude of ways, appear senseless? And how do people, particularly children, respond to individuals in crisis and communities under siege? In this essay, I take up these complex questions within the theoretical and practical backdrop of my ongoing research program. I feature photographs and texts excerpted from my longitudinal research studies at Martha Maude Cochrane Academy, a grade 4-5 magnet school located in the mid-southern US. I do so to show how children's lives lived in storied schools prior to the September 11th tragedy contributed greatly to the meanings the students were able to make in context and, in turn, share with others. It will soon become evident that unexpected metaphorical connections—metaphorical commonplaces—existed between scenes of New York City and education at Cochrane Academy before the events of September 11, 2001 and that these formed the very real backdrop within which the students of Cochrane Academy created the Shadows of New York mural—a mobile parkland space that they gifted to the citizens of New York. To understand how this occurred, the theoretical background to this parkland inquiry will be presented. It will be followed by several narratives offering different scenes of Cochrane Academy that build up to the New York connection which eventually becomes enacted. |

|

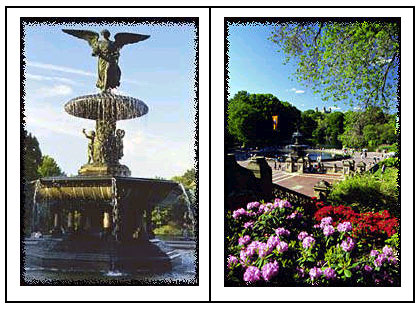

Background to the InquiryIn the mid 1990s, I conducted narrative inquiries at Riverview School and Evergreen School in a western Canadian city (Craig, 2000) using Clandinin and Connelly's (1995, 1996) metaphor of a "professional knowledge landscape" to narratively reconstruct the contexts within which teaching and learning took place. Clandinin and Connelly (1995) described their landscape idea in the following way: ...a landscape metaphor allows us to talk about space, place, and time. Furthermore, it has a sense of expansiveness and the possibility of being filled with diverse people, things, and events in different relationships... It [is] both an intellectual and moral landscape (p. 5)... In responding to my article and others published in Curriculum Inquiry 31:3, Diamond (2000) emphasized the generative nature of the professional knowledge landscape metaphor and suggested that the idea of schools be re-shaped – and contextual inquiries re-conceptualized—as parkland. To make his point, Diamond drew attention to the deliberate re-landscaping of a barren area of New York City in 1858 to create what is currently known as Central Park. (Note 1) The restoration was done to promote social reconciliation and add to the developing sense of community. Diamond painted the picture this way: Crafted to offer dense woodland, open formal spaces, artificial lakes and terraces, 30 elegant bridges and arches, bridle paths and rambles, the park was created on an unpromising site of quarries, shacks, and swampland. Ten million cartloads of stone and earth and a half a million trees and shrubs transformed the landscape into a lush series of composed views. The park with its captured sense of nature is arguably the 19th-century America's great work of art. (p. 2)   As part of the theoretical frame for this essay set at Cochrane Academy but focused on the events of September 11th, I pick up on Diamond's idea of schools transformed as parkland and merge it with Clandinin and Connelly's professional knowledge landscape conceptualization. With these metaphorical notions firmly in mind, I then narrate how the story of Martha Maude Cochrane Elementary School, now Martha Maude Cochrane Academy, a campus located in a historical African American community, was altered—re-landscaped, so to speak—to address historical inequities and injustices. This will provide readers with the necessary background to understand how and why Cochrane 5th grade art students dealt with the Ground Zero events in the manner they did and, in the process, helped others—in addition to themselves—to cope and heal. Like a Georges Seurat (Note 2) painting, this inquiry will feature a pointillated constellation of stories (Craig, under review) that will bring different essences of Cochrane Academy's nuanced landscape into view as well as the overall panoramic view. Images and text will first be excerpted from fieldwork undertaken between May 1998-August 2001 and then from September 2001-December 2001. The metaphorical landscape I will reconstruct particularly will be composed of a shifting story of community and a developing story of school brought about by a federally imposed story of reform—reform story (Craig, in press). The diverse people, things and events in different relationships that I introduce to the moral, aesthetic and intellectual landscape will build up to what transpired in a 5th grade art class in the aftermath of September 11. The inquiry will end with an overview of the ways in which the narratives in this school as parkland study inform one another and how they are richly instructive to an educational enterprise that is deeply entrenched in historical baggage and accountability rhetoric. |

The Story of Hardy Community—Hardy Community StoriesDocuments in the school and local archives, local history items, newspaper clippings, interviews with administrators, teachers, parents, students, and community leaders, and participant observation notes gathered during three years of field study at Cochrane Academy form the field texts on which this research text is based.The Hardy community in which Cochrane Academy is located was developed during World War I when African American citizens purchased acre plots of land, built homes, and assumed agrarian lifestyles. Livestock such as chicken and horses were raised and produce was grown for personal consumption. Highly popular, the neighborhood increased in size to the point where a 1950s newspaper called it "the largest all-Negro community in the United States" (School Reform Proposal, 1998-1999). The Hardy community currently covers an expanse of 7600 acres, crosses three school districts, and reflects striking contrasts in terms of old and new, rural and urban, and poverty and wealth. In the vicinity of Cochrane Academy, spacious homes sit alongside subsidized apartments and seemingly endless cottages, the majority of them showing advanced signs of aging. Still other properties look abandoned while others appear to be inhabited by temporary dwellers. In short, the neighborhood around Cochrane is, as a current educator describes it, "about as far removed from a cookie cutter community as one could possibly imagine." Two thoroughfares pass through the Hardy neighborhood near Cochrane Academy. Located immediately in front of the school, the latter one was completed as recently as 1998. All other roads near Cochrane are more like rambling lanes and bear names reflecting the history and folklore of the local people. Roads such as Salvation Corner, Pecan Street, and Banjo Lane abound. Small churches and businesses are sprinkled abundantly throughout the Hardy neighborhood. They continue to exist because some citizens walk to institutions and businesses as they go about their daily routines. Thrift is the order of the day where stores are concerned whereas spiritual revival is a common theme shared by the churches. Hence, signs like "Bargain Basement Prices" appear side-by-side with "A New Day Coming ..." To individuals born and raised in the community, the neighborhood around Cochrane is a place where African American citizens "dug roots" and "formed wings." A prominent community leader, for example, spoke of the neighborhood in the following manner: "I was reared here and am very proud. No community is any greater. There are outstanding people, personalities, resources, and leaders here. I am blessed to be a part of it." Another local leader, also raised in the community, concurred with the aforementioned opinion. She also emphasized the "dignity and sense of pride in community" and "the tight connection between family and community." She particularly referred to a specific street that was closed for parades, homecomings and other festivities. For her, the Hardy neighborhood was fondly recalled as a community "with a lot going on for children." But the neighborhood surrounding what was Cochrane Elementary School changed dramatically in the decades that followed. It regrettably declined to the point where it was openly storied as a community "plagued with poverty, unemployment and crime." The street once distinguished for its parades and celebrations became known for its drug dealing activities. A leading African American educator agreed with this portrayal of the community transition. To him, a common public perception of the neighborhood around Cochrane was that it was "a rough, drug-infested, crime-riddled neighborhood." At the same time, though, the individual recognized the historical roots linking Cochrane Elementary School and its community. He explained: Prior to forced desegregation, the community had a lot to do with education. It had a rich history, not in terms of dollars, but in terms of the value the community placed on education. In the neighborhood, schools were highly prized. Everyone knew about the academic, social, and athletic contributions of schools. The faculty delicately stated a similar view in school documents: Education has always been important in this African American community, but African American people in America historically have been denied the right to empower themselves through education (p. 1). This combined sketch of stories of community—community stories lays the groundwork for the Cochrane Academy story of school—Cochrane Academy school stories that follow. Narrative threads that anchor Cochrane in its community and metaphorically link it to the development of Central Park in New York City will become increasingly obvious. |

Cochrane's Story of School-Cochrane School StoriesSources in the local archives, school portfolios, reform proposals, evaluation reports, local history publications, newspaper clippings, interviews with administrators, teachers, students, parents, alumni, and community members, and participant observation notes gathered during three years of field study at Cochrane Academy form the evidence from which this institutional account has been distilled.The history of Cochrane Elementary's story of school remarkably preceded the construction of an educational facility. A 66 year old black female city leader of prominence noted that early in the segregation years, the Hardy community had only one school that was crowded to the extent that students attended in shifts: first in two shifts, then in three shifts. Due to school overcrowding, one black father of three children 'crossed over' to a white neighborhood of his own accord. The voluntary crossover resulted in the recognition of the educational needs of the African American community. As a result, more schools were built in the neighborhood with Cochrane Elementary School being one such construction. These developments addressed the overcrowding situation even as it allowed racially segregated schools to continue to exist. Named after a prominent African American educator, Cochrane Elementary School originally was designed to educate poor, black children in a segregated setting where community, academics and athletics were of vital importance. Later, when it became apparent that schools in the urban area were going to desegregate, the vast majority of people in the vicinity of Cochrane embraced Martin Luther King's "I Have a Dream" vision. They desired equal education and access to facilities. They longed for well-appointed schools and new instructional material for teachers and students to use. They did not want "hand-me-down sports equipment" and "discarded books filled with other (white) people's names." At this point in time, however, the community members did not know lending support to school desegregation would mean that the plot lines of the campuses in their neighborhood would be drastically changed, even extinguished. In what later became a "forced scenario," African American students were redistributed throughout a geographically large school district that was majority white but would soon become majority minority. (Note 3) For instance, in one year, 1850 young Hardy students were transported to schools outside the neighborhood. This enormous flight from community resulted in Cochrane's feeder pattern junior high school being turned into an alternative behavior campus, Cochrane Elementary School serving rotating grades of students, and the closure of the feeder pattern high school offering a comprehensive program. In the case of the latter campus, many of its trophies, photographs, and certificates were destroyed (community members salvaged some), and the symbol on the high school—rumored to be an early work of a student who became a professional artist—was taken down, and later reported as stolen. These developments, among others, gave rise to serious, almost irreparable, mistrust between the formal institution of schooling and the African American community that the local schools once served. It also divided the Hardy community into a number of factions represented by rivaling Chambers of Commerce and civic groups that have yet to reconcile. In the aftermath of the initial wave of desegregation policy, many African American people felt "taken advantage of." Additionally, parents and community leaders who once were more united had become fractured. Contact with black youngsters also was not maintained to the same degree. Youth were scattered throughout the school district and some parents did not have transportation to attend to problems as they previously had done when they walked to schools in the neighborhood. A period of seventeen years passed. During this time of rapid socio-economic change, the educational possibilities for neighborhood children did not expand in the manner anticipated. When some African American leaders gathered to formally consider the academic progress of the students in their new settings, it was readily apparent that the schools and children had been stripped of "community and family support." Furthermore, the attitude that "certain kids could learn and certain kids could not learn" formed a "psychological barrier" that had become pervasive. Students additionally found few or no teachers of the African American race with whom to identify in their new school settings. Also, there were not only changing laws with which to abide, there were also changing modes of discipline with which to come to terms. As one prominent African American educator from the pre-desegregation years put it: We were pretty strict–both the school and the community... [In the crossover], a generation of children learned freedom away from the watchful eyes of teachers and community members. The youngsters did not understand it well. In handling freedom, the students neglected to do what they should have done academically. In this individual's opinion, the crossover situation contributed to less than satisfactory student achievement and enormously influenced lives lived, and stories told, by African American students who then became the next generation of parents. Concerns for the educational growth of black students at Cochrane Elementary (now Cochrane Academy) and other neighborhood schools have reverberated since then. In addition to the less-than-expected academic growth of African American students, other information pertaining to the Hardy community was made public. As with other urban, minority neighborhoods, relationships were shown to exist between and among intergenerational illiteracy, intergenerational poverty, poor housing and poor community infrastructure. In 1990, for example, 32% of the citizens in the vicinity of Cochrane Elementary School were found to be living below the poverty level. Included in this percentage were 1650 single parent families, a figure that suggests a high incidence of child poverty. Furthermore, 40% of the residents aged 25 and over who lived in the neighborhood around Cochrane had not graduated from high school. Statistics such as these prompted community leaders and the school district to return to the federal justice system in 1994 to explore better ways to serve the educational needs of black youth. A number of plans were entertained. A district official, who worked diligently to regenerate the school, explained how events unfolded in the following conversation: First of all, the district was under court order since 1977 for desegregation purposes. That court order required busing. ...There was no choice. In 1994, some [Hardy] community members...approached the district about re-looking at that plan to see if there was something we could do to have neighborhood schools so that elementary children particularly would not have to be bussed across the district... So we began that process with a visit to the Justice Department... The Department would not allow us to do that because we would return [Cochrane Academy] basically to a one-race school... And so we looked at various plans, held various focus group meetings in the community, and decided on the magnet school plan. [Cochrane Academy] became one of the first of two magnet schools. This birthing process that gave rise to a new story of school for the campus formerly known as Cochrane Elementary School. The magnet school concept introduced to Cochrane Elementary struck a compromise between the culturally relevant, intimate campus that community leaders desired for African American children and the letter of the law that dictated options. This led to the school being renewed and re-named Cochrane Academy for Mathematics, Science and Fine Arts. This development left other district schools with regular programs and all of the competitive sports teams in the district. Having traced the concurrent development of Cochrane's story of school and school stories told over time, Cochrane's story of reform and reform story will now be narrated separately. Attention to students' interests, the celebration of cultural and ethnic diversity, as well as the fostering of student achievement within an environment of choice – the hallmarks of the magnet story of reform—will be described, then illuminated. The Magnet "Story of Reform"Court order documents, literature about magnet schools, grant proposals, evaluation reports, school brochures, interviews with administrators, teachers, parents, students, and community leaders and participant observation notes gathered during three years of field study at Cochrane Academy informed this account. The different iterations of educational struggle that took place in the Hardy community over time gave rise to a grassroots, second wave attempt to revamp Cochrane's story of school through the introduction of a legally mandated story of reform. The bottom up/top down effort set its sights on making the community a safer place to live, aggressively returning education to the community, and focusing relentless attention on children and the special conditions that might support their learning (Cochrane Academy Reform Proposal, p. 1) Because community members living around Cochrane Academy wanted to restore neighborhood schools and the school district was already working under a 1977 desegregation order, the Justice Department was necessarily involved. A very complex process began to take place. In 1995, the Justice Department stipulated eleven objectives with which the school district needed to adhere within a five-year period (1995-2000) in order to be in successful compliance with the desegregation order. These objectives called for additional black faculty involvement in decision-making processes, an integrated student population, as well as a number of other stipulations. To finance the expansive story of reform mandated for Cochrane's story of school and other stories of school in the particular district, a major magnet school proposal was written and submitted to the US Department of Education. In the fall of 1995, the school district was awarded a $7 million dollar grant from the Magnet Assistance Program. The award provided the funds for the development of the original magnet schools of which Cochrane Academy was one and startup funds for five additional magnet campuses. From the very beginning, the magnet schools were meant to meet the needs of all students as opposed to a specialized population, although a portion of the students living in the Hardy community would always be guaranteed admittance to Cochrane and other neighborhood schools. To ensure a balanced racial population at Cochrane Academy and other schools, an electronic lottery was instituted that determined who would attend. The theory of action (Argyris & Schön, 1978; Schön & McDonald, 1998; Hatch, 1998) underlying the magnet school approach was to provide enhanced educational experiences in the existing African American community while maintaining a desegregated school population. This would be accomplished through attracting non-black and black students from elsewhere in the school district to the unique programs, top-notch facilities and state-of-the-art equipment that distinguished Cochrane Academy from other district schools. This narrative turn formed a sharp contrast to the way the 1977 desegregation order was previously lived by students educated in the school district. It also paved the way for possible connections to be nurtured between the arts, social justice, and education at Cochrane Academy. These promising dynamics were foreshadowed in the words of Cochrane's lead art teacher, Elaine Wilkins, who perceptively explained when my research at the school began: Whenever people have a history of being downtrodden and oppressed, the arts thrive. The arts and social justice walk hand in hand. That is why arts-based education works at Cochrane Academy. The emphasis on the arts addresses the existence of historical struggle of the Hardy community and the community's desire to re-write its future. |

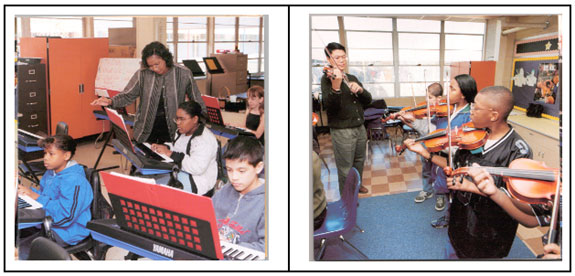

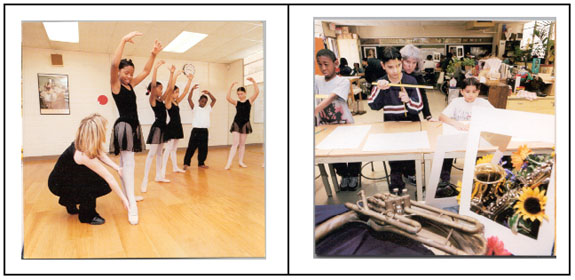

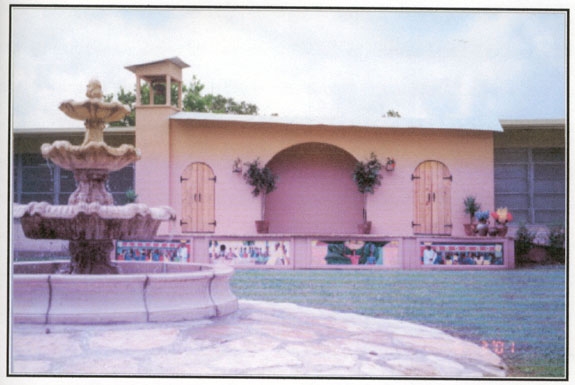

Reform StoryThrough the use of photographs interlaced with research text, a portrait of how the magnet reform story became lived at Cochrane Academy will be presented. The reform story takes the form of a walking tour of the campus. The account draws on three years of fieldwork captured in interviews, participant observation notes, photographs, document analysis, evaluation reports, reviews of school portfolios, and summaries of school survey data. The student-painted wooden lounge chairs, bright benches, and primary colored poles supporting the external walkways between classrooms at Cochrane Academy signal that an arts-centered place of learning is being entered.  An enormous John Biggers-inspired (Note 4) painting at the entrance of the school confirms the passing hypothesis. Anchored with seasonal sketches of the pecan trees that line the internal courtyard of the school, the representation aesthetically projects the magnet themes of the campus. The inclusion of the pecan trees, revered by the local African American community, serves as a reminder of how Cochrane's social narrative history reaches into the past, is lived in the present, and projects into the future (Dewey, 1938) with new ideas being seeded and old ones being cast aside.  Upon entering Cochrane Academy one is not only visually captivated by the sights of learning, one is also confronted by the sounds of learning. Walking down the corridors, one hears students practicing piano, violin, and tap dancing and singing joyfully in a chorus. Echoes of dramatic productions taking place in the black box theatre/classroom can also be heard.  |

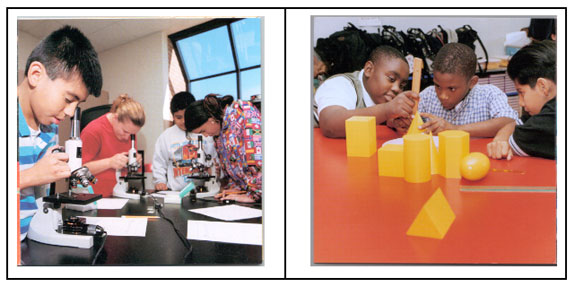

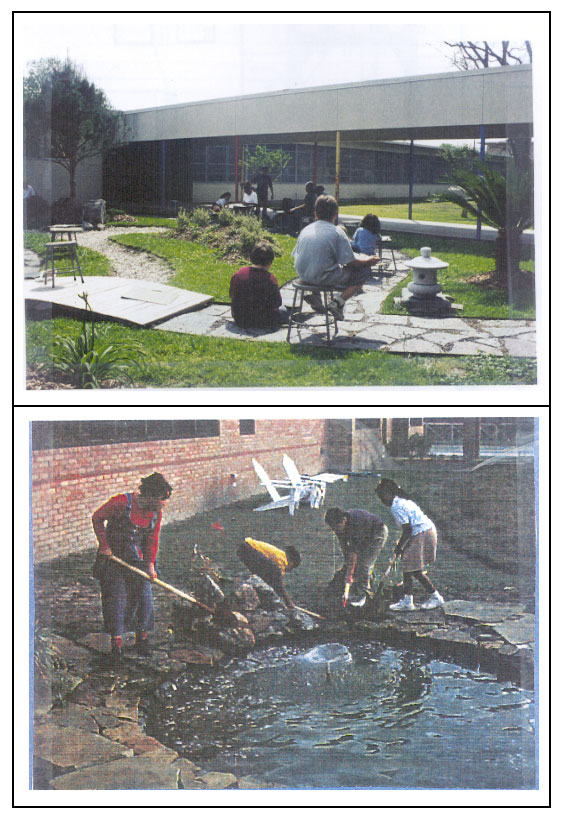

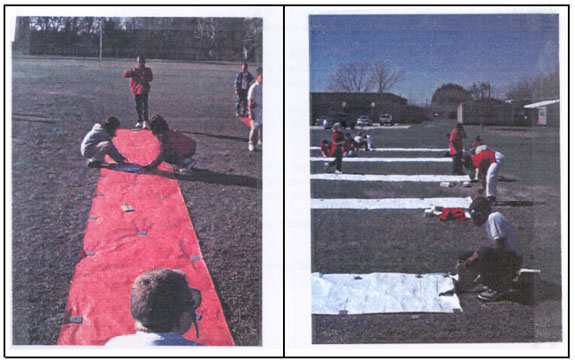

As one peers in classroom windows, one sees students practicing ballet in the dance studio classroom or developing perspective in art class under the mindful direction of their teachers.  One also views students using manipulatives in mathematics and high quality microscopes in newly constructed high technology, science labs, labs whose construction was required by the Justice Department and was made possible by the federal magnet school grant.  Walking on, other expressions of learning become visible. A Japanese Garden of Silence and an Insect Sanctuary, for example, are encountered in the internal courtyard spaces. In these places, students experience tranquility and actively care for their environment.   Inside Cochrane Academy classrooms, hands-on, multi-disciplinary learning is highly evident. Students can be seen learning mathematical terms like 'diagonal,' 'square,' 'line' and 'circle' as they study works of art. They also create dance movements to tunes like "Rocky Top," a popular Blue Grass song that students in cooperative learning groups later perform. Overseeing this latter activity is a mathematics teacher and a choreographer, who was born and raised in the Hardy community, an individual that has worked with many prominent black artists, including Michael Jackson. Later, the students meet with their mathematics teacher and the 'learning through the arts' teacher to artistically depict the shapes they have studied. |

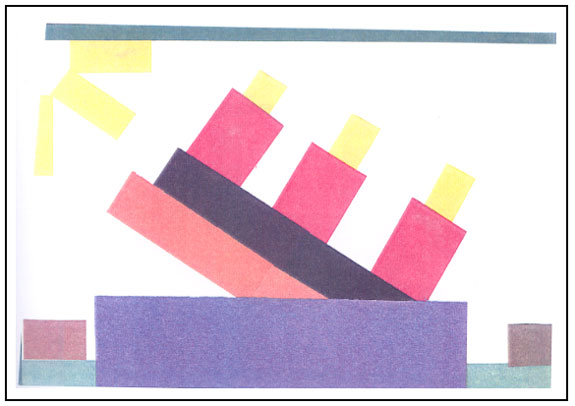

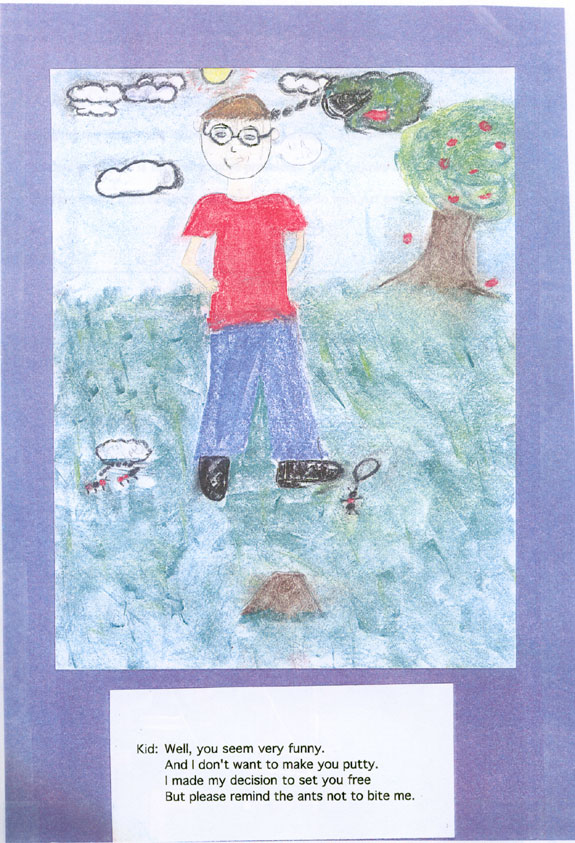

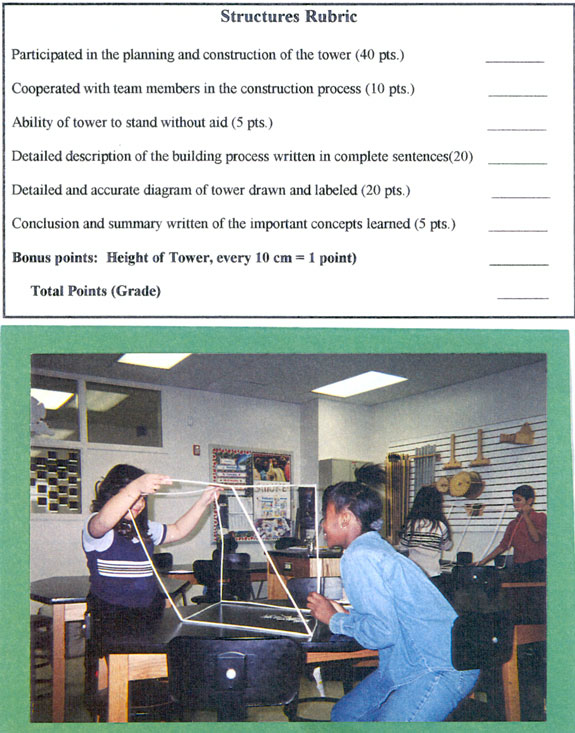

In another classroom, students analyze Stuart Davis's (Note 6) (1938) picture, Glouster Harbor and borrow Davis's cubist style to form their own works of art. Below is one student's artistic rendition, which is followed by the 10 year old's written response to Davis's and his own artistic representation.  Stuart Davis's picture, Glouster Harbor, was made in 1938 with oil on canvas. It is a very bright, bold and colorful picture. He uses different kinds of shapes in his picture. He mostly uses rectangles. Every time you look at it you see something different. I see two boats with ladders in them sometimes. Other times what stands out to me is a mountain. It is a very bright yellow. The picture that I made is a red, black, orange and yellow boat sinking in the ocean. It is kind of like the Titanic. I used brown and green for the land, and I used yellow rectangles for the sun. Elsewhere on the campus Cochrane students may actively participate in experiments like "the marble launch" which combines skills in mathematics, technology and science. Students are required to roll marbles at pre-determined angles and to record the distance the marbles travel. They then create computer spreadsheets and line graphs from which they will make a series of predictions. In the process, the Marble Launch Pads become mobile parkland spaces where knowledge can be enacted within the school grounds.  In another classroom, students differentiate between point of view and perspective as commonly defined in literature and art. After reading the children's literature book, Hey, Little Ant by Phillip and Hannah Hoose, their teacher invites them to write their own versions of a stanza to the story, a stanza that will represent the point of view of both the boy and the ant. Here is one student's artistic representation and interpreted text:  Not only is instruction experientially grounded at Cochrane Academy, so, too, is evaluation. The science rubric and image that follow illustrate students immersed in an authentic assessment task where they perform what they have come to know about structures, how they are constructed, how they can be self-supporting, and how to work cooperatively in a group to create free-standing products. |

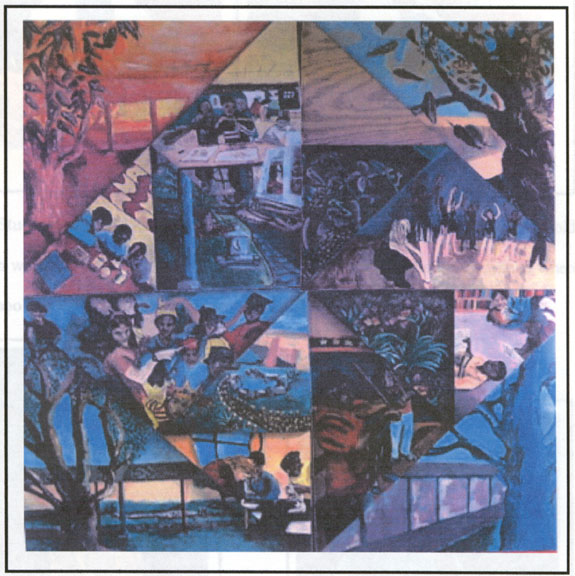

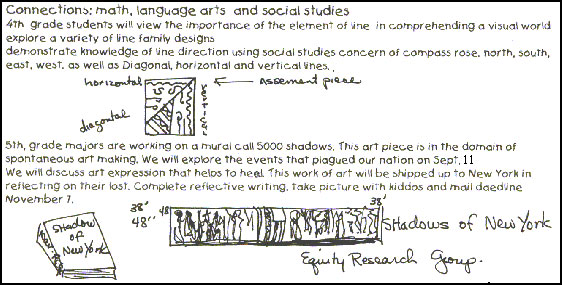

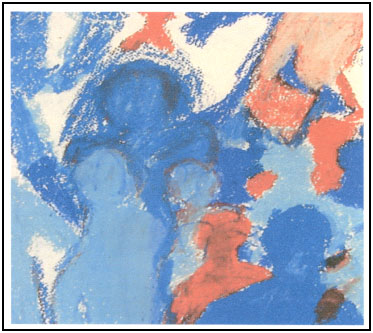

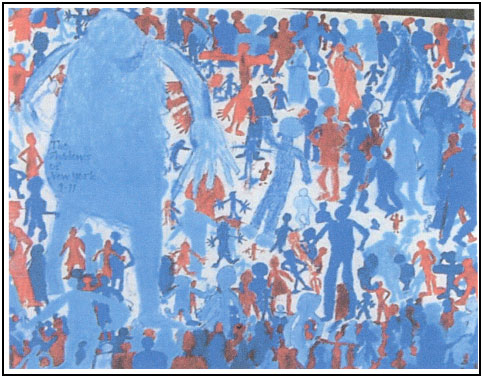

So far, the photographs and narrative passages capture "composed views" of Cochrane's arts-based landscape and project key scenes of the school's magnet story of reform. The walking tour format illustrates how Cochrane Academy is infused with arts-based learning and a mathematic, science, and fine arts program and is possibly one of the late 20th-century America's greatest educational models of intermediate schooling. However, what can never be forgotten is that Cochrane Academy arose from an inequitable, politically charged situation; its history deeply etches its past and present and will continue to shape the contours of its future. With this background of struggle in mind, we will now examine how the 5th grade art students at Cochrane Academy responded to, and made sense of, the events of September 11th. In the narrative that follows, we will discover that the children not only commemorated those whose lives were lost in the New York debacle, but they demonstrated in deep and powerful ways how oppression of all kinds can be challenged with time and attention, even in the most constraining of situations. A Post-September 11 Story at Cochrane AcademyThis narrative was constructed from lesson plans, participant observation notes, photographs, excerpts from student reflective essays, text from letters written by the teacher, and interview data gathered from September 2001—December 2001. Prior to September 11, 2001, the 5th grade art major students at Cochrane Academy concentrated on the skill of shading. As their teacher put it, "the instruction was geared toward developing their artistic abilities... what was taking place in the classroom was pretty ordinary..." But then the September 11th tragedy happened and, according to the teacher and students, "all that changed." The shading exercise that began as a somewhat mundane skills lesson became transformed into a profound experience of art making. A reflective mural of healing was created for the people of New York and was presented to an equity firm whose workplace was destroyed and numerous employees annihilated in the World Trade Center chapter of the disaster. (Note 7) The mural and the shades of meaning it held for the teacher and the students will now be unpacked.It is fitting to begin this story with the perspective of Elaine Wilkins, the art teacher who was born and raised in Brooklyn, New York. After all, it was through her initiative and creative energy that the healing project materialized and took on a life of its own. In a letter written to the equity firm in New York, Wilkins explained: Since September 12, my students have immersed themselves in creating an artwork for healing. To all who are grieving for the loss of family and friends, we are hopeful our mural will speak volumes... With its American flag, its shadowy victims all interconnected ("larger figures represent[ing] rescue workers") and its re-creation of "the lady who stands... for what we believe," the mural indeed spoke volumes. But in the beginning, the mural was merely a seed of an idea that was an expression of Elaine Wilkin's personal practical knowledge (Clandinin, 1986). This is evident in the sketch that follows, which reflects her plans for her students' art experiences. |

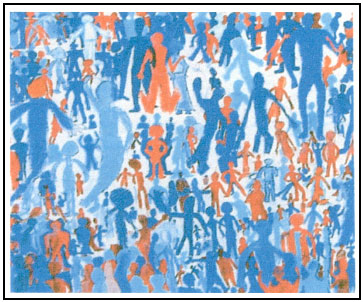

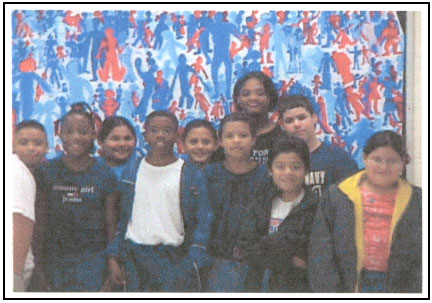

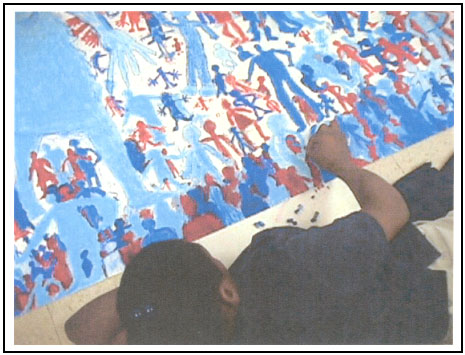

The children, in turn, reflected on their teacher's embryonic mural idea and the seed germinated in their minds as the next photo suggests.  Like Cochrane's other Grounds For Learning, the mural eventually became birthed as a parkland space in the entrance hallway of the school. The memorial tribute to New York City temporarily upstaged the prominently displayed Biggers-inspired painting portraying the school's magnet programs nested in the history of the Hardy community. It also dwarfed the Sculpture Garden, the intended art integration project for the 2001-2002 school year.  Readers can well imagine the thought and effort students expended to create 1000+ shadows on a 38"x 48" canvas. One student explained: |

... the mural shows shadows. Some may say, "Why shadows?" They represent the thousands of people missing and gone. The shadows are in red, white, and blue—the colors of America. Nathan, age 10. (Note 8) Another said: Our goal was to have one thousand shadows. Before we had eight hundred, but now we have one thousand. But there were many more people who were killed in New York City. David, age 10. |

For the children, the images on the mural were not simply shadowy figures to be drawn and counted, but expressions of deeper meaning. For example, one student explained what he hoped others would see in their "shades of meaning" art work: If you look closely at the mural, it looks like the people of New York are hugging, playing, running, and holding hands. They will always be together. Michael, age 10.  He went on to say: This mural represents all the people who died and to let you know that each shadow is not alone. They are together in groups and some of them are holding each other's hands. Michael, age 10. |

|

Another student explained: I drew a family praying. This picture is at the top right hand corner of the mural. My shadows are people expressing their feelings... Ashley, age 10.  Still other students reflected: I am writing to say that I am praying for all the people who did not receive their loved ones home that night. Thy'Asia, age 10.  For the students and their teacher, Elaine Wilkins, the mural and the concurrent reflective writing and conversations represented something positive they could contribute to the healing process (Note 9) —for themselves personally and for the people of New York to whom they were reaching out: |

I am angry but I can now hold my anger very well. Justin, age 10. |

Reflective CommentsIn this essay, I have laid stories beside one another to represent the pointillated school landscape that has developed over time at Cochrane Academy. I have done so to reveal how the particular campus was borne of struggle and how addressing struggle and celebrating culture—through collaborative work projects undertaken in metaphoric parkland spaces—is an integral, ongoing part of Cochrane's revised story of school as lived. This essay illustrates that what happened in the heels of the September 11th events in the 5th grade art class was a natural outpouring of what had taken place at the school prior to the tragedy. The development of keen social awareness and the capacity to respond meaningfully to the underside of experience are not abilities that are mysteriously found when disasters strike (as they inevitably do); they are abilities that are mindfully cultivated amid the multiple stories children daily live as part of regular life on storied school landscapes. The arts-based learning approach I have showcased here is not "fluff" which those trapped in the accountability metaphor and others who cannot see past its critique have been inclined to call it. Rather, it exemplifies a profound blend of knowledge, skills, and dispositions that have been purposefully brought together to deepen experience, broaden meaning and sustain humanity. Not only is art lifted out of the realm of pastime and play for the privileged and placed squarely in the domain of public school, it is used in a manner that heightens meaning over time and is transferable to other real life contexts. In this work, it is apparent that The Shadows of New York memorial tribute, which temporarily graced Cochrane's front hall, appeared as another in a series of permanent and mobile parkland spaces in the school. Like the permanent Biggers'-inspired canvas and the Hispanic Plaza of Knowledge, the mural of healing became a productive Ground For Learning to deal with an aberrant event, a grievous incident that was not of individual New Yorkers' or Americans' making. Like the Japanese Garden of Silence, the Shadows of New York formed a venue for reflective contemplation within which students could dig deeper for meaning. And like a combined Marble Launch Pad/ Insect Sanctuary, it was rolled up and sent off to New York City to become a sacred memorial to the victims who perished and to offer sanctuary, hope and inspiration to those people and businesses whose lives must continue despite the grim reminders of the Ground Zero events that envelop them.Author NoteThe author acknowledges the centrality of the experiences of Elaine Wilkins, her students and the community-based participants who contributed greatly to this work. Thanks are also extended to graduate research assistants, Cazilda Campos Steele and Sreekanth Nadella, who helped in the technical preparation of this manuscript. Research support for this inquiry was provided through sub-contracts from a reform movement and the U.S. Department of Education. The Kraft Foundation funded the Cochrane Academy's Hispanic Plaza of Knowledge. Release forms granting permission for the use of students' photographs, writing and artwork are on file at Cochrane. Cochrane Academy is a pseudonym I have given the campus. The equity firm is also referred to anonymously due to continuing security risks. Notes1. Over 50 scenes of New York's Central Park can be viewed on the Central Park website (http://www.centralpark.org). 2. Georges Seurat was an artist who rebelled against the impressionist movement. He used only the tip of his brush with which he set down dots of color. This technique became known as pointillism. 3. Majority refers to the greatest number of students while minority means all students who are non-white. The expression means the school district is mostly composed of non-white students. 4. John Biggers was a local African American artist who painted in the narrative tradition and whose symbolic murals portray African American and African cultural themes. Information concerning John Biggers and his work is available at http://www.getty.edu/artsednet/resources/Biggers/bio.htm/. 5. Diego Rivera, who lived from 1886-1957, was a Mexican Social Realist Muralist. Like the artwork created by John Biggers, Diego Rivera's murals are locally and nationally recognized. More information concerning Rivera and his paintings can be found at http://www.artcyclopedia.com/artists/rivera-diego.html 6. Stuart Davis is the foremost US artist who worked in the cubist style. Further information on Stuart Davis and his creative works can be located at http://www.ibiblio.org/wm/paint/auth/davis/ 7. The mural was received on behalf of the city of New York by Mayor Giuliani. The equity firm's receipt of the gift was recorded on the front cover of a major business journal. The mural will be displayed in the board room of the company's new headquarters. 8. The 5th grade student comments are stated in their own words. The passages were excerpted from longer essays. A binder containing the students' written work was sent to New York alongwith the shadow mural. 9. My writing of this article serves a similar purpose, particularly since I am a Canadian who lives and works in the U.S. and who has closely witnessed the devastating effects of the September 11th tragedy on American citizens. This paper forms my attribute to those whose lives were lost and to those who must carry on. BibliographyArgyris, Chris & Schön, Donald (1978). Organizational learning: A theory of action perspective. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. Clandinin, D. Jean (1986). Classroom practice: Teacher images in action. Philadelphia: The Falmer Press. Clandinin, D. Jean & Connelly, F. Michael (1995). Teachers' professional knowledge landscapes. New York: Teachers College Press. Clandinin, D. Jean & Connelly, F. Michael (1996). Teachers' professional knowledge landscapes: Teacher stories-Stories of teachers-School stories-Stories of school. Educational Researcher, 19(5), 2-14. Craig, Cheryl J. (2000). Stories of school/teacher stories: Two variations on the walls theme. Curriculum Inquiry, 30(1), 11-42. Craig, Cheryl J. (2001). The relationships between and among teachers' narrative knowledge, communities of knowing, and school reform: A case of "The Monkey's Paw." Curriculum Inquiry. 31: 3, 303-330. Craig, Cheryl J. (under review). Story constellations: A way to contextualize teacher knowledge. Dewey, J. (1938). Education and experience. New York: Collier Books. Diamond, C. T. Patrick (2000). Turning landscape into parkland: Difficulties in changing direction. Curriculum Inquiry, 30:1, 1-10. Hatch, T. (1998). The differences in theory that matter in the practice of school improvement. American Educational Research Journal, 35:1, 3-31. Johnson, Mark (1987). The body in the mind: The bodily basis of meaning, imagination and reason. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Lakoff, G. & Johnson, M. (1980). Metaphors we live by. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. MacIntyre, A. (1984).After Virtue. Notre Dame, Indiana: University of Notre Dame Press. Schön, Donald A. & McDonald, Joseph P. (1998). Doing what you mean to do in school reform. Providence, RI: Brown University. About the AuthorCheryl J. Craig, Ph.D.304E Farish Hall University of Houston Houston, TX 77204-5027

|