International Journal of Education & the Arts | |

Volume 3 Number 7 |

December 24, 2002 |

Some Manifestations of Ghanaian Indigenous Culture in Children’s Singing GamesMary Priscilla Dzansi |

|

Abstract

This article discusses some Ghanaian cultural values and expressions that are embedded in children’s playground repertoire. The discussion is based on the description and interpretation of some of the songs children performed for me during my fieldwork in Ghana in 2001. Ghana has embarked on school reforms and policies to make school music reflect the culture of the local communities. As I analyzed some children’s repertoire within the cultural contexts in the Ghanaian indigenous communities, it is evident that the playgrounds and homes are fertile grounds for tapping and honing their artistic potentials to enhance and transform music performance in the classroom and beyond. |

Introduction

Music teaching and learning in Ghanaian Schools have suffered an unfortunate situation in the elementary schools and teacher training colleges for decades. The curriculum is based on Western music concepts and aesthetics from the elementary school level to the tertiary level (see Akrofi, 1982; Flolu, 1993, 2000; Manford, 1983). Students dodged their music lessons and nicknamed the subject the “Most Useless Subject in the School Curriculum” (Music). The irony is that, in the Ghanaian communities, music is alive; performance is participatory and based on everyday life and activities (Nketia, 1974). Students and teachers enter the classroom with a rich experience of Ghanaian music in their local communities, or the macro, which is the larger community context, but their education background, including the music syllabus, operates within the ‘institutional context’ [Western] (See Bresler, 1998; Nketia, 1970; Okafor, 1991).

Conceptual/Theoretical Framework

Music education of late is using ethnomusicological insight and approaches in order to understand the character of a music culture—its subcultures, such as children’s music, and community music (Campbell, 1998; Nettl, 1983; Welsh- Asante, 1993). In other words, ethnomusicologists attempt to capture a broad knowledge, both culture and music, or the way music is used within the indigenous wider context (Merriam, 1964). Elsewhere, Nettl (1983) suggests that it is time for music education students to take more courses in ethnomusicology to expose them to community music of different types, as well as to ways of making music in the communities to cross over to their music education courses. Moreover, contemporary trends in music are geared towards more awareness that music is basically a diverse human practice and not concerned only with Western aesthetic concepts (ISME, 1994; Oehrle, 1992). Most importantly, children are part of a larger culture, and their playground singing games manifest a great deal of what goes on in the macro community as far as beliefs, values, identity, and meaning are concerned (Agu, 1992; Campbell, 1998; Nketia, 1974). Apart from the nonsense syllables or meaningless songs, the texts of the game songs are based on everyday living and experiences (see Nketia, 1974; Nzewi, 1999; Okai, 1999). Based on the above concepts, I undertook an ethnographic study, “Cultural Expressions in Children’s Playground Music in Ghana,” in 2001. As I analyzed some of the repertoire of my participants, I unearthed not only enriching but also insightful interpretations which I share in this article.

Method

Data were gathered from three schools and one neighborhood in Ghana for a four- month duration. I selected three schools: two schools, namely Deladem School in Tema, and Lebene School in Ashaiman, are in the Greater Accra Region in Ghana and both schools are located in big cities. The other school, Ganyo Primary School, is located in the rural area of Saviefe Agorkpo in the Volta Region of Ghana, and the Emanuel Villa neighborhood in a suburb of Ashaiman. The rationale for selecting these schools for my study is to have a variety of ethnic groups represented in the study. Ghana is a multiethnic community and every ethnic group speaks a different language (this discussion follows). The participants in my study were between the ages of five and fifteen in the elementary [Basic] school. I spent a month in each school as a participant observer in all the data collection settings. I observed children on playgrounds and recorded their conversations during recess. I also learned to play some games with the school children and taught them some of the games I played when I was their age. I recorded the playground songs on audio and video taped them during their performance twice a week. I interviewed 12 teachers from each school and 10 parents from Emmanuel Villa neighborhood.

Ethnicity in Ghana

The official language in Ghana is English. There are nine major languages that are taught in the schools under the umbrella of “government-sponsored languages;” namely, Ga, Dangme, Akan, Ewe, Dagaare/Wale, Kasem, Nzema, Gonja, and Dagbane (Ghana Census, 2000). There are hundreds of dialects that are spoken in Ghana that are non-government-sponsored. Interestingly, a majority of the children’s repertoire I collected are in Ewe and Akan languages with a few in Ga.

One of my data settings, Ganyo School, is in the Volta Region of Ghana where the language is Ewe and all their songs are sung in Ewe. The songs performed for me by students in Ashaiman are in Ewe and Akan since the suburb of Ashaiman, where Lebene School is located, is heavily populated with the two ethnic groups, and the Children from the neighborhood of Emmanuel Villa also performed most of their songs in Ewe and Akan due to the ethnicity of their parents. The students from the city of Tema, however, performed most of their songs in Akan, English and Ga. It is interesting that most of the songs were known across all schools and each group performed it in the language- click of that school. Thus I recorded some of the same games but in different languages. A typical example is Amesi wo dzi Dzoda in Ewe and Obiara woa wu Dzoda in Akan.

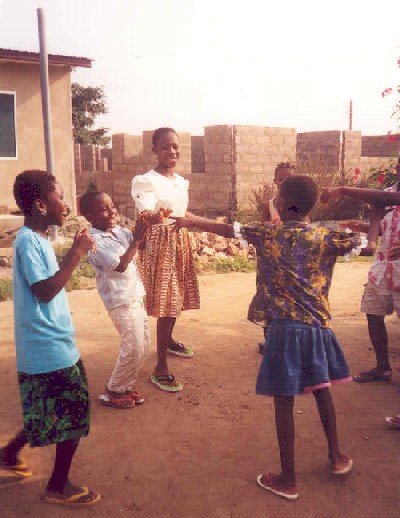

Figure 1. Children are the preservers and transmitters of culture on the playgrounds. Emmanuel villa neighborhood children in Ashaiman, Ghana (Picture by Mary Dzansi, 2001)

Content and Context in Children’s Repertoire

In my research, I identified several categories or themes of Ghanaian culture in children’s playground repertoire, for instance, X⊃m zu atidudu de m⊃ to (imagine I am chewing stick at the road side). Other categories include cultural ideologies that are very symbolic, for example Torgbui Zikpui (the royal stool) (see Algotsson, et. al, 1996). Some of the songs are filled with ritual meaning, for example, Srodede nu nyia de (Marriage is a good thing), and proverbial and idiomatic expressions, such as ati k⊃k⊃ de mu kpla dza (a tall tree has fallen with its branches). The songs also revealed individual and group identities, example one Amesi wo dzi Dzoda (whoever is born on Monday) shows this vividly. For the purpose of this article, I will discuss three game song texts and their contextual implications in indigenous Ghanaian culture and their educational implications.

|

Example One Amesi wodzi Dzoda b⊃b⊃ Translation: Whoever is born on Monday [Performed by Deladem, Lebene and Ganyo Schools, 2001] |

Names and Identity in the Ghanaian Context

Naming ceremonies are important in Ghanaian communities regardless of their religious backgrounds. The child is named after a living relative, or an ancestor of the family and clan given a name with a biblical connotation. For example, the name Amete¦e (In place of) is given to a child who resembles a relative in the family who has died. The family consoles themselves with the belief that an important person who is lost to the family is being replaced. A given name during outdooring ceremonies could be Makafui ( I will praise Him) or Az⊃ko (At long last). Newborn babies are named on the eighth day after birth in a ceremony at dawn or in the early hours of the morning. These naming ceremonies are not Christian baptisms but indigenous practices that initiate the baby into the community and are accompanied by music making and feasting. Church baptisms are performed later in the life of the child or adult. During naming ceremonies, the newborn baby is given water and any local brewed gin to taste, symbolizing the facts of life, and to bless the child that he or she may be a truthful member in the community, and be able to differentiate good from evil when he or she grows up. In the Ewe community, the senior uncle or aunt from the father’s clan will dip his or her finger into the wine for the child to lick. The naming ceremony is performed by a relative of the baby’s father’s lineage because it is a patrilineal community. This practice differs from one ethnic group to another; the Akans perhaps may prefer the uncle from the mother’s side to be the master of the ceremony because they practice matrilineal inheritance.

Before the naming ceremony, however, the child is already called by the day of the week she/he is born. For example, when a baby girl is born on Monday (Dzoda), she will automatically be called, “Adzo or Adzoa.” If a boy’s birth occurs on a Monday, he is called “Kodzo, Kudzo or Kwadzo,” thus all Monday ‘borns’ share the same name. The spellings and pronunciations vary according to the language of the various ethnic groups.

Below is a chart of weekday borns:

| Local names of the week | Girls | Boys |

| Dzoda (Monday) | Adzoa, Adzo | Kudzo, Kwadzo, or Kodzo |

| Blada (Tuesday) | Abra, Abla or Abena | Komla, Kwabena |

| Kuda (Wednesday) | Akua, Aku | Kweku, Koku |

| Yowoda (Thursday) | Yawa, Awo, or Yaaya | Yawo |

| Fida (Friday) | Afi or Afua | Kofi or Fifi |

| Memleda (Saturday) | Ama, Ame | Kwame, Kwami |

| Kwasida (Sunday) | Esi, Awusi, or Akosua | Kosi, Kwesi |

The importance of the weekday names is manifested in daily living and activities. For example, when an important personality gets up to dance during a special occasion, he or she is extolled as “Adzo” “Afi”, “Akosua,” and so on. As a matter of fact, anyone who gets applause for doing an extraordinary deed is called by his birth name “Afi, Awo, Ame,” and so on. The feminine version is used in the appellation even if the recipient is a male.

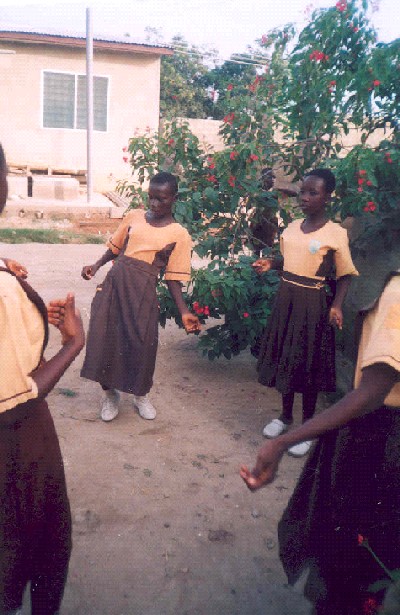

Figure 2. Emmanuel villa neighborhood children performing a clapping game (Picture by Mary Dzansi, 2001).

Example Two

Ya ye ye ye ye, ya ye

X⊃m zua tidudu le m⊃to

Atidudu ye

Gbeke fa Dzi va yie ne gem du. 2x

Translation:

Ya ye ye ye (meaningless rhythm)

Suppose I am a chewing stick tree by the roadside

So that when my lover is passing by,

He may break a piece and chew.

The Love for Natural Forms: Chewing Sticks

In the Ghanaian community, almost everyone chews a piece of stick to clean the teeth or freshen up the mouth. There are special species of tress that are cultivated or growing wild that are used as chewing sticks. There are also different herbs that are chewed to protect the teeth. In most rural areas, people have never used toothpaste and toothbrushes in their lives. “My father and grandparents have never used toothpastes,” said Kodzoga (Saviefe, 2001). Kodzoga’s mother is a schoolteacher so she uses toothpaste as well as chewing sticks. The rural people do not know what toothpaste is; they always rely on natural chewing sticks to take care of their teeth.

Everyone chews a piece of stick some time during the day to care for the teeth or to freshen up. The educated people use toothpaste and brushes in the morning and at night, but somewhere in between they will chew chewing sticks or if they run out of toothpaste, they substitute it with chewing sticks until they shop for more. Some ethnic groups in Ghana chew local sponges or herbal roots early in the morning to clean their teeth. These sponges are twining or climbing plants that are dried and beaten into fine sponges for chewing. The sponges are identified more with the Ga and Dangme ethnic groups in Ghana. A whole ritual-like chewing of sponges exists among Ga women. Ga women will take at least 10-15 minutes to chew their sponges after which they will take a bath before doing any chores in the morning. Whereas, other ethnic groups will have a piece of stick in their mouth in the morning as they go about their morning chores or whenever they crave for a piece of stick to chew, especially after a meal.

The personification of the chewing stick in the song alludes to its importance in the Ghanaian community. Children from the Saviefe traditional area in Volta Region of Ghana performed a complicated clapping rhythm game on playgrounds to accompany this song. The metaphor of a woman missing her lover and wishing she were a chewing stick by the roadside so that whenever "Adzi" (lover) passes by, he may break a piece and freshen up. The text is very significant, because Ghanaians are bound to break off a piece of any type of tree or plant they know is edible as they walk by in order to freshen up their breath.

The importance of chewing sticks is manifested in this Ya ye ye game. “Suppose I am a chewing stick tree at the road side, so that when my lover passes by, he may break [me] and chew.” I recorded the same song at the neighborhood playground of Emmanuel Villa in Ashaiman. Their text reads: “suppose I am a chewing stick tree at the road side, so that whoever passes by may break [me] and chew.”

Example ThreeYa ye ye ye ye, ya ye

Wome d⊃a me dud⊃e da sime o

Ame dudue ye

Va fle te ve wo ts⊃a ‘gbeli fle

Va fle te ve wo ts⊃a ‘gbeli fle

Ye wots⊃ ‘gbeli fle.

Translation:

A stupid fellow is not sent to the market.

Oh stupid fellow

When sent to buy yam,

She/he went and bought cassava

Yes, she/he bought cassava.

[Performed by Ganyo School, 2001]

The Significance of Ethnic Foods

The distinction between yam and cassava in this song is very important and significant in the context of food delicacies in Ghana. It is also important as far as farming and festivals are concerned. In the Saviefe traditional area where the students from Ganyo School performed this game song, the community is an agrarian one.

The yam species that are planted throughout Ghana are big, long tubers that if the rains fall and the soil is rich and fertile and a farmer devotes his time to his crops, a yam tuber could feed a family of eight to ten children. Yam cultivation is more tedious and demanding than cassavas. Mawunyo, who won the best farmer award in 2000 in the Saviefe farming area confirmed, “Yam farming is tedious, I learned from my father that staking yams high, weeding the farm regularly, and digging around the mounds to remove extras from the stem, yield good harvests” [Saviefe, 2001].

Cultural Significance of Foods: Yam Festival Celebrations

Most communities in Ghana that grow yams, including the Saviefe traditional area, celebrate annual yam festivals with dancing, singing and pageantry. The festivals are celebrated in the months of August through December. Every yam-growing community selects a date between the months of August to December. In case the rains delay during the season, and the planting and harvesting are late, the natives adjust their festival calendars accordingly.

Food festivals in Ghana are celebrated for several reasons, and the yam festival is not an exception. Festivals are celebrated mainly to give thanks to the gods for a good harvest, to ask for abundant rains for the next planting season, to bring out the symbolism of a crop, and to bring natives from the cities back home to the rural areas. It is also a time for family reunion and socializing, and to raise funds for community projects in the various towns and villages.

In the Saviefe farming villages, for example, no farmer is supposed to bring new fresh yams to the village until the chief and his elders have performed a ritual ushering in of the new yams. The ritual takes the form of drumming and a cleansing of the town Gb⊃me Kp⊃kpl⊃ (literally sweeping of the town). A few elders of the town who are the masters of ceremony tie a branch and drag it through the town, while one priest carries a small pot of water and sprinkles it through the town, driving out all evil spirits and plagues. When this is completed, the elders mash some yam for the chief’s stool and declare the celebration of the yam festival open.

Due to the indigenous norm that no one is to expose any yam until the day of the yam festival, natives smuggle yams quietly to their homes to cook but no one speaks of it outside. Mensah tells me, “Once you are able to smuggle it and cook secretly, no one bothers you, but if you expose the crop and bring it to town, you are going to pay a fine in drinks or a ram” (Saviefe, Nov, 2001). (Schnapps and rams are the traditional fines or delicacies of chiefs and elders in the Ghanaian communities among almost all ethnic groups.) The day before the festival celebration, the ban is lifted and everyone is free to bring yams to the town that evening. Children follow their parents to the farm for the harvest in order to display their tubers for everyone to see. Every child from the age of six who is capable of carrying a load has a number of yams tied with ropes to be brought to the town. It is fun to bring new yams to the village, because as soon as you reach the outskirts of the town, people shout an appellation of the yam obo, obo. “I remembered when we were children we loved it, especially when our parents’ yams were so big and long during the season” [Avima, Ashaiman, Dec, 2001].

During the morning of the festival, almost every household prepares fufu and the rhythm of pounding is heard throughout the town. Fufu is a Ghanaian delicacy prepared from pounded yams or cassavas. The yams are boiled and pounded in a mortar with a pestle by one person, or two people each holding a pestle. The actual durbar, or the royal gathering, begins at 10 or 11 am with different activities and in the presence of several drumming groups. It is climaxed with singing, dancing, and fundraising activities in the form of birthday or weekday competitions, popularly known as Kofi and Ama (see example one). Ghanaian hospitality is at its peak during yam festivals. All the visitors from the cities have to be fed by their relatives during the week-long celebrations.

The significance in valuing yams over cassavas in the community can be attributed to the hard work that accompanies the cultivation of the crop. Most importantly, the pomp and pageantry surrounding the celebration of yam festivals bring out the symbolism in the song, “it is stupid on the part of a person to buy cassava instead of yam.” The song teaches children to be vigilant and know what is valuable in their communities. It is a great felony to mistake cassava for yams.

Summary and Conclusions

In this article, I exposed the reader to the cultural contexts in which Ghanaian students’ games songs are situated. It appears children are ‘just playing’ and their playground repertoire doesn’t matter, but when interpreted and analyzed, the customs and practices that underlie them are rich sources of cultural significance. The significance of the customs embedded in children’s playground singing games will go a long way to enhance classroom music teaching and learning. Students will appreciate their music lessons more when their playground content and context are expressed in formal learning. In their “Traditional Songs of Singing Cultures,” Campbell, Williamson, and Perron (2001) refer to teachers as preservers and transmitters of their own cultural heritages. That might be true to some extent when it has to do with mere collections of folk songs, but from my research perspective, concerning children’s playground performances and repertoire, I attribute the preservation and transmission of indigenous and cross cultural diversity to children. Children’s play songs, especially the texts, and the music are typical representations of the Ghanaian indigenous culture (see also Amoaku, 1976; Nketia, 1974).

Figure 3. The dramatic action of these students speaks louder than words: music and culture are alive on playgrounds (Lebene students, Ashaiman, 2001) [Picture by Korkuvi Mac-Palm who assisted with the camera during my research]

Educational Implications

The indigenous contexts of the songs could serve as a rich source of reference for music education in formal music education settings. Teachers could develop children’s repertoire into a vast variety of materials in the teaching and learning of indigenous culture and music in the classroom. For example, children could perform their indigenous games in class so that teachers could use them to teach aspects of indigenous culture, such as music, dance, drama and narrative. While children clap, tap, jump, and dance to their singing games, teachers could use the music elements of each game to suit the objectives of the day’s lessons. For example, describing the melodies as simple, repetitious, sequential, wherever appropriate. Students could diagram the contour of the melodies and come up with their own symbols to write down the songs. Students could choreograph new dances to accompany “Ya ye ye” or “Amesi Wodzi Dzoda” and other game songs. Children could also compare the melodic patterns of different game songs. For example, what is happening in Ya ye ye pattern? What is the difference between the melodic pattern of Amesi Wodzi and Ya ye ye? Or what is happening in the two game songs rhythmically? Students could also compose responses to calls and vice versa in their game songs (I attached the notation of Amesi Wo Dzi and Ya ye ye below. The yam song and the chewing stick songs have the same tune).

In indigenous music pedagogy in the Ghanaian communities the holistic approach is the norm. In other words, the song texts, the activities and the music are equally important (Dzansi, in press). Therefore, students could be asked to enact music dramas depicting the events surrounding the song texts, for example, the celebration of the yam festival, outdooring and naming ceremonies. Each game song tells a story, and students could be asked to narrate the story or write their own stories and accompany them with singing, drumming and dancing as it happens in indigenous Ghanaian culture (refer to Kwami, 1986). The games also expose both students and teachers to the cultural diversities in the Ghanaian communities. In other words, what are the characteristics of African music manifested in each ethnic group as far as their values, their beliefs and their symbolism are concerned? Finally, the indigenous content and contexts of the songs could serve as a rich source of reference for music education in international settings or under the popular term ‘multiculturalism.’

( By Deladem, Lebene, and Ganyo Schools, Ghana, 2001)

(By Emmanuel Villa, Ashaiman, and Ganyo School, Ghana 2001)

References

Akrofi, E. (1982). The status of music education programs in Ghanaian public schools. D.ED. dissertation. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Algotsson, S., & Davis, D. (1996). The spirit of African design. Clarkson Potter Publishers.

Amoaku, K. W. (1976). Some aspects of change in traditional institutions and music in Ghana. Masters Thesis. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Bresler, L. (1998). The genre of school music and its shaping by meso, micro, and macro contexts. Research Studies in Music Education, 11, 2-18.

Campbell, P., Williamson, S., & Perron, P. (1996). Traditional songs of singing cultures: A world sampler. Warner Bros. Publications.

Flolu, E. J. (1993). A dilemma for music education in Ghana. British Journal of Music Education, 10, 111-121.

Flolu, E. J. (2000). Re-thinking arts education in Ghana. Arts Education Policy Review, 101, 25-29.

ISME. (1994). Policy on music of the world’s cultures.

Kwami, R. (1986). A West African folktale in the classroom. British Journal of Music Education, 3, 5-18.

Manford, R. (1983). The status of music teacher education in Ghana with recommendations for improvement. Dissertation Abstract International, 44, 2703A.

Merriam, A. (1964). The anthropology of music. Evanston, IL : Northwestern University Press.

Nettl, B. (1983). The study of ethnomusicology: Twenty-nine issues and concepts. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Nketia, J.H. (1970). Music education in Africa and the West. Music Education Journal, 57, 48-55.

Nketia, J. H. (1974). The music of Africa. New York: W.W. Norton &Company, Inc.

Nzewi, M. (1999). Strategies for music education in Africa: Toward a meaningful progression from tradition to modern. International Journal of Music Education, 33, 72-87.

Oehrle, E. (1992). An introduction to African views of music making. Journal of Aesthetic Education, 25, 162-174.

Okafor, R. (1991). Music in Nigerian education. Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education, 108, 58-68.

Okai, D. (1999). Musical games of the people of Adankrono and their educational implications. Unpublished thesis. University College of Education of Winneba.

Welsh-Asante, K. (1993). The African aesthetic. Greenwood Press.

About the Author

Mary Priscilla Dzansi is finishing her Ph.D. in music education at the University of Illinois in Urbana-Champaign. She is a lecturer at the University of Education, Winneba in Ghana. Her research area includes children’s playground and popular music innovations, and indigenous music in formal music education. She is on the Advisory Boards of the Arts and Learning Research Journal and the International Journal of Education & the Arts.