|

Review

Kellman, Julia. (2001). Autism, Art, and Children:

The

Stories We Draw.

Westport, CT: Bergin & Garvey.

160 pages

$52.95 ISBN: 0-89789-735-8

Reviewed by Sally Gradle

University of Illinois

at Urbana-Champaign

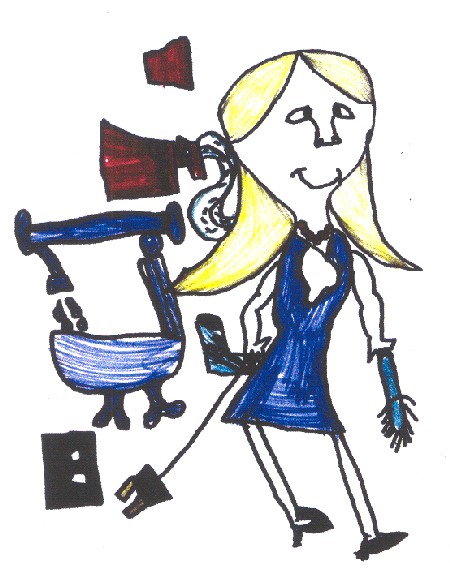

The

Queen of Makeup, Peter, age eight, marker on paper.

Used

with the

author’s permission.

Author Julia Kellman has honed a thoughtful

craft

of reflection in Autism, Art, and Children

(2001). We are

transported into a realm where sense making in art requires

diligent interpretation of experience if one is to

understand the

autistic child artist. Gone are the more familiar methods

that

help us examine child art; such as dialogue with young

artists or

observations of social engagement in art

making. Furthermore, we

must free ourselves from the logic bound constraints of

science

in order to plumb the depths of meaning in this uncharted

territory. This may best be accomplished by adopting a more

natural narrative to construct meaning that is a

“creative,

fluid undertaking;” Kellman

suggests, “…for it

is in the flow of events and lived experience that children

and

art making come together” (p. 4). The author’s

discussion of intersubjective meaning, as defined by

Zurmuehlen,

Coles, and Schutz, reveals a belief that the stories we

tell each

other and ourselves allow for sense making in our

lives.

This established, Kellman leads us on to her particular

intentions in this research. Her approach is

phenomenological

and anthropological; one that will focus on case studies of

autistic children as valid child artists rather than

disabled

students. This tack has a hidden strength: through

narrative,

the phenomena of experiences engage us in looking at these

unusual artists in ways that a more objective, rational

approach

might discount. This broad based observational stance has

afforded Kellman the opportunities to learn from the worlds

of

others through a larger array of observable events, rather

than

limiting her vantage to defining and labeling behaviors of

disabled artists.

In the second chapter, Kellman continues her positive

observations; citing several shared characteristics that

exemplify precocious autistic art makers. Early or sudden

onset

of drawing skills, content that is visually based, and a

descriptive style that defines and structures their art

through

the use of line are among these interesting

characteristics.

Because the world of autistic children is isolated from the

sociocultural engagement that occurs in usual interactions,

Kellman suggests that moments of visual learning are

“made

longer and more accessible to them by autism” (p.

17).

Without the self-awareness and the dictates of a peer-enhanced,

circumscribed social world, the autistic artist is more

open to

the sense of “now.” While Kellman is not

suggesting

that this explains all autistic creation, she does set the

stage

for further elaboration about particular case studies.

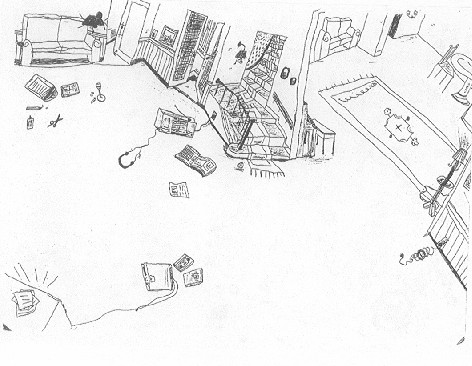

Living Room, Jamie, age seven, ballpoint on paper.

Used with the author’s permission.

We meet, for example, a young man at a center for

disabled

adults who repeats zigzag markings on sheet after sheet of

paper

while looking anywhere but his work. He is apparently

satisfied

with this repetitious visual outcome. Kellman poses an

interesting question that the reader may be asking as well

at

this point. Does this scenario offer insight into how

autistic

and non-autistic artists see? To answer, Kellman turns to

research on the brain, citing neurobiologist David

Marr’s

((1982) explanations for how the brain develops. Art that

exploits early vision, characteristic of the autistic child

artist, “emphasizes the process’s attributes in

regard to the structure, location in space, and

directionality of

objects,” Kellman informs us (p. 25). The

unconceptual

nature of autistic art, coupled with the visual acuity of

the

artist in apprehending structures of forms in three

dimensional

space, link them with other visual thinkers who organize

their

worlds spatially. Kellman further clarifies this with the

example of autistic designer and researcher, Temple

Grandin, who

enlightens the reader, saying that relationships made

little

sense to her until she began to visualize them as a series

of

doors and windows one must open and close in social

interactions

(p.29).

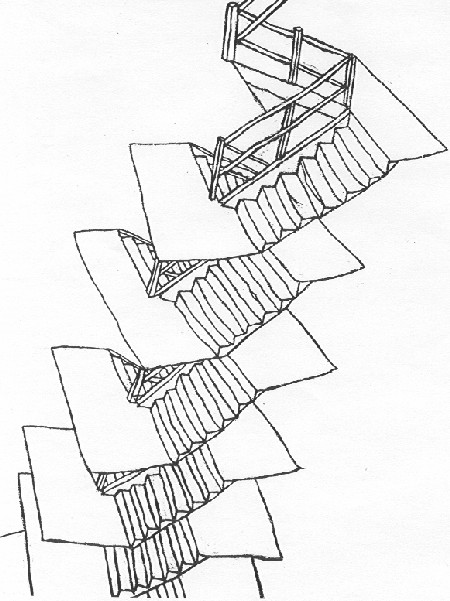

Stairway, The towering

Inferno, Jamie, age seven, pencil on paper.

Used with the

author’s

permission.

Continuing to build on the strengths of such

visual thinking, we are introduced to Jamie, the

architectural

planner who is a gifted shaper of spaces, one who defines

whole

worlds of detailed interiors such as elevators, car

engines, and

ventilating systems. Through his work, we see that the

relationship of form to meaning is essential. Kellman

informs us

that it establishes a structure which allows feelings to be

shared. The less culturally derived lens of the autistic

artist

thus forms a unique art expression—one which we could

easily dismiss—without Kellman’s narratives

illustrating how seeing is a “prelinguisitic

undertaking” (p. 32) that anchors all of our meaning

making. “For art in its very substance and structure

provides individual artists—Jamie and others--with a

sense

of mastery, meaning and coherence at the same time that it

affords viewers a glimpse of artistic resolve and personal

narrative” (p. 48).

In a similar manner, we are introduced to Peter, Katie,

and

Mark; each of whom illustrate ways of being with art that

acknowledge the importance of image as it becomes a

meaningful

text of their lives through a language of

form. Kellman’s

prose is precise, and wonderfully descriptive of behavior:

“...when I patted his shoulder in thanks for a job

well

done, he winced, dropping down and sideways to avoid my

hand. It

was as if I had burned him” (p. 44). “Tongue

clicks,

hums, and a long, deep bell-like tone suggesting a movie

soundtrack composed to describe deep space or perhaps to

imitate

the sound of distance chanting Tibetan monks also accompany

the

shouted warnings and commands” (p. 80).

Characters from The Wizard of Oz, Peter, age

seven,

ballpoint on paper

Used with the author’s permission

With a thorough investigation of the research on the

causes

and diagnostic trends of autism in children, Kellman

grounds her

observations in further evidence from genetics, embryology,

and

neurobiology. Although she notes that no single cause or

definitive answers have been uncovered, Kellman suggests

that

“the cascading events that cause changes in the early

developing fetus likely produce the condition of

autism”

(p. 102). She observes that the exemplars of this study

could

well inform us of the role the qualities of autism play in

the

making of art. As a marker of experience, “the

momentary,

the individual, and the particular” can be understood

as

“preattentive aspects of the vision

process” (p.

103).

So what are we to take away from this insightful book?

Clearly, we are now freed from the bondage of

meaning-as-social-construction alone. Some other

construction of

meaning is possible in the hidden realm of autistic,

artistic

vision. Likewise, we have learned that language by itself

is

insufficient in guiding our interpretation of this visual

narration. We must examine in context how it is lived by

the

artist as an internal expression made visible. As Kellman

suggests, it is as though “Orpheus singing into being

the

very actions of a world” (p. 84), retrieves meaning

from a

place and establishes through such artful action that which

is

common to us all. Finally, this study is both positive and

hopeful: acknowledging the strengths of the autistic

artists

rather than their more usual description of need. There is

much

we have yet to understand through further study and

reflection on

the art of the precocious artist child. However, as

philosopher

Paul Ricouer (1965) states, “[The] recuperative

reflection

is certainly the philosophical impact of hope, no longer

the

category of the “not yet” but in that of the

“from now on” (pp. 12-13). Autism, Art and

Children shares insight and inquiry from just such a

viewpoint.

Reference

Ricouer, P. (1965). History and Truth. (C. A.

Kelbley,

Trans.), Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press.

About the Reviewer

Sally Gradle is a doctoral student in Art

Education at

the University of Illinois, and a veteran art teacher in

the

local public schools. She is interested in documenting

artists’ encounters with the sacred in their work and

has

presented her work in AERA and NAEA.

|