Doorways to the Academy:

Visual Self-Expression among Faculty Members

in Academic Departments

Marybeth Gasman

University of Pennsylvania

Edward Epstein

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Citation: Gasman, M. & Epstein, E. (2003, December 31).

Doorways to the academy:

Visual self-expression among faculty members

in academic departments, International Journal of Education

and the Arts, 4(8). Retrieved [Date]

from http://www.ijea.org/v4n8/.

Abstract

In this article, we seek to understand how faculty door

displays can evolve into an elevated form of self expression

rather than mundane decoration. Other research on this topic has

linked the decoration of faculty doors to theories of

personalization: the need to mark the territory as belonging to

the owner and as a symbol of commitment to an institution. Our

discussion, however, focuses less on the personal and more on the

use of the door as a means of positioning oneself within the

department, institution, and discipline. We find that faculty

door displays encompass more than just matters of personal style

but also touch on the larger concerns that the professor wishes

to communicate to the academic public.

A walk through the hallway of any academic department can

reveal much about its culture (Kuh and Whitt, 1998). For an

observer tuned into visual phenomena, there is a lot to absorb:

human beings given a space of their own will rarely leave it

empty of decoration (Altman, 1975; Greenbaum and Greenbaum, 1981;

Hansen and Altman, 1976; Schiavo and Miller, 1993). An artist and

a member of an academic department, the authors of this paper

began to notice the particularly potent kinds of adornments that

occur where faculty members are given wide latitude. The question

arises: how do faculty members, who are in the business of

self-expression, express themselves visually?

Visual self-expression is not exclusively the domain of

artists, but may be practiced by a variety of groups in many

settings. For university faculty, the office door provides a

convenient site for such a display (Schiavo, Madaffari, and

Miller, 1999). Much like a blank canvas, the door is an empty

space that a professor can fill with images and texts that

furnish clues to his or her beliefs, interests, and philosophy of

learning (Kaye and Galt, 2002). Faculty members, of course, are

not the only ones who embellish their work spaces. Other sites

for this type of decoration include office cubicles, work areas

in a factory, and school lockers or residence hall doors. Unlike

the school locker or residence hall door, however, the faculty

door assumes an official status. It is a threshold through which

students, colleagues, and members of the general public must pass

to do business with a particular faculty member—a kind of

intellectual store window through which professors profess.

According to psychologists R. Steven Schiavo, Jennifer West

Miller, and Tia M.I. Madaffari, “Office doors are

particularly relevant since they serve as a gateway [that]

provide[s] a visible introduction to the occupant”

(Schiavo, Miller, and Madaffari, 1998, p. 2). And unlike its

corporate counterparts, the faculty doorway is situated in a

context where the reigning traditions of academic freedom

guarantee a unique openness of expression (Becher, 1994; Kuh and

Whitt, 1998; Ruscio, 1987). Whereas in the corporate setting, a

worker may be forbidden to post any materials that contradict the

company’s stated philosophy or suggest that he or she is

not a “team player,” faculty members can and do post

whatever they see fit. This may include materials that ridicule

the theoretical leanings of others, suggest a strong political

slant, or disparage the institution in which they are located.

It can also include a display of non-traditional hobbies and

interests or an openly gay/lesbian lifestyle (Rhoads and Tierney,

1992).

With these observations in mind, we set out to explore the

phenomenon of faculty doors. We catalogued the types of things

put on doors, and their relationship to the college environment.

Were they merely bland and functional (e.g. a pocket in which to

hand in papers)? Did they seek to provoke some sort of response

(e.g. a political diatribe)? Were they funny? Were they

haphazardly placed, or did they try to achieve a kind of harmony

with respect to color and arrangement? How did they reflect the

professor’s stated views and research agenda, as expressed

in his or her publications? Many of the doors, in fact, worked on

multiple levels. With their heterogeneous array of images and

texts, they could convey a complex picture of the person who sat

behind them (Schiavo, Madaffari, and Miller, 1999).

Using a psychological framework, other research on this topic

has linked the decoration of faculty doors to theories of

personalization: the need to mark the territory as belonging to

the owner and as a symbol of commitment to an institution (Hansen

and Altman, 1976; Vinsel, Brown, Altman, and Foss, 1976; Schiavo

and Miller, 1993). Still others have used survey research to

examine student responses to faculty doors (Schiavo, Miller, and

Madaffari, 1998). However, our approach was closer to that of a

semiologist: decoding the messages imbedded in the decorations

themselves and asking how they convey meaning specific to the

academic audience. In the same way that semiologists have

studied advertisements, we looked at the systems of meaning that

faculty doors employ to communicate with the university community

around them (Barthes, 1977; Barthes 1957; Williamson, 1978). Our

research was less about the faculty member’s effort to

relate to his or her colleagues on a personal level, and much

more about how he or she used the decorations as another means to

convey positions on important academic, political, and social

issues. We explored the idea that faculty doors can be an

elevated form of self-expression – a visual and verbal

position statement directed at the department, institution, and

discipline. This naturally led to a discussion of the history

and ideology of the university, and particularly the notion of

academic freedom (Hofstader, 1961; Metzger, 1961). It underscored

the uniqueness of the university environment, and how it differs

from that of other institutions such as corporations or

government agencies.

Reflecting on the multi-layered expression found on the doors

led to the question of whether they themselves were a kind of

art. In entertaining this suggestion, we followed conceptual

art’s tendency to ask the question “what is

art?” by proposing new and unusual objects as art (Godfrey,

1998). In this part of our examination, we compared the

professor’s arrangement of heterogeneous materials on a

door—images, texts, and objects—to the assemblage

tradition in visual art. Rooted in dada and the notion of the

“readymade,” this way of making art finds meaning in

commonplace objects by presenting them in new settings, sometimes

in enigmatic combinations with other objects. This is not to say

that we attempted to “prove” that faculty doors are

or are not art; only that art provided a valuable framework

through which to discuss faculty doors. As well as considering

these ideas in this paper, we devised another way in which to

explore the doors’ artistic nature: a multi-media

installation based on the material we found on them. This part of

the project, which is now under development, will take place

within the context of an art gallery or alternative exhibition

space and will include full-scale photo reproductions of the

faculty doors. (Note 1)

Methods

George Kuh and Elizabeth Whitt note that to provide a rich

description of an institution’s cultural properties,

methods of inquiry are required that can discover core

assumptions and beliefs held by faculty, students, and others and

the meanings various groups give to artifacts. Techniques of

inquiry appropriate for studying culture include observing

participants, interviewing key informants, conducting

autobiographical interviews, and analyzing documents (1998, p.

vii).

Our research focuses on the analysis of documents or artifacts

and began with an examination of actual faculty doors. We also

observed the interactions of people within the departments

(students, faculty, and staff). We hoped to learn how the doors

could inform our understanding of the culture of the department

and institution in which they were located. From the outset, we

made it a goal to examine the doors of faculty in diverse types

of colleges and universities. We selected three institutions with

different cultures and missions: Georgia State University,

Spelman College, and Emory University (all located in Atlanta,

Georgia).

Knowing that academic culture varies by discipline, we chose

to focus on a single field for all of the institutions we visited

(Kuh and Whitt, 1998). We sought to discover the ways in which

discipline influenced the selection of materials to place on the

door. Because English is a staple department in almost every

institution of higher education in the United States (and thus we

could expect to find a sizeable English department on any campus

we visited), we chose it as the focus of our study. We sent email

messages to all of the faculty members in the English departments

of Emory University, Spelman College, and Georgia State

University. Our email message contained a brief description of

the research project and asked faculty members if we could

photograph their door. From those who agreed to participate, we

requested a current curriculum vitae and a signed release form.

We visited each of the departments on a Wednesday afternoon

between 3:00 p.m. and 6:00 p.m. Using a digital camera, we

photographed a total of 35 faculty doors, and made written

observations of the remaining doors in the departments (10 doors

at Emory University, 14 doors at Georgia State University, and 11

doors at Spelman College). In addition, we spent time observing

the activities in each department. Upon processing the photos,

we looked for themes and modes of self expression. We compared

these to the existing literature on departmental culture, English

department culture, and faculty expression. In addition, we

reviewed the faculty curriculum vitae to understand individual

interests, activities, and backgrounds.

Institutional Descriptions

Spelman College – A small, private liberal arts

college, Spelman is one of two historically black colleges for

women in the United States (Bennett College in North Carolina is

the other one). It was established in 1881. The primarily

residential college is a member of the Atlanta University Center

consortium and is located on the southwest side of Atlanta.

Through this affiliation, the 2100 Spelman students enjoy the

benefits of a small college while also having access to the

resources of the five participating black colleges that make up

the Atlanta University Center (Brazzell, 1992; Cox, 1985;

Edelman, 2000; Guy-Sheftall, 1982). According to Spelman

College’s statement of purpose,

The educational program at the College is designed to give

students a comprehensive liberal arts background through study in

the fine arts, humanities, social sciences, and natural

sciences. Students are encouraged to think critically and

creatively and to improve their communicative, quantitative, and

technological skills (Spelman College Statement of Purpose,

1999).

Moreover, Spelman purports to “reinforce a sense of

pride and hope, develops character, and inspires the love of

learning… Spelman has been and expects to continue to be a

major resource for educating black women leaders” (Spelman

College Statement of Purpose, 1999).

Georgia State University – Located in the heart

of downtown Atlanta, Georgia State University is an urban

research university. Although students have been non-traditional

in the past, the current student body reflects a more traditional

(18-22) aged student. With an enrollment of over 27,000 students,

Georgia State offers 52 undergraduate and graduate degree

programs in over 250 fields of study. In addition, the

institution boasts opportunities for participation in innovative

research projects and community involvement. Established in

1913, the institution’s ties to the local urban community

permeate its mission and its strategic plan (Flanders, 1955).

According to its internet site, Georgia State University

“breaks the ivory tower mold of higher education and makes

the most of its urban home by bringing teaching, research and

service to life.” By combining “traditional

university education with the unique opportunities found in a

growing international city, Georgia State University allows

students to learn not only in the classroom but also in the busy

surrounding city, where high profile companies provide hands-on

experience” (Georgia State In-Depth, 2002).

Emory University – Located just minutes from

downtown Atlanta, Emory University is a private research

university with over 11,000 students. Emory was founded at

Oxford, Georgia by the Methodist Church in 1836 (English, 1966).

The institution is composed of nine major academic divisions,

numerous centers of advanced study, and several affiliated

institutions. According to the university’s president,

“Emory strives to help its students, faculty, and staff

[members] achieve their highest aspirations: to discover truth,

share it, and ignite in others a passion for its pursuit”

(Chace, 2002, n.p.).

University Culture

According to George Kuh and Elizabeth Whitt,

“institutional culture is both a process and a

product.” It is “revealed through an examination of

espoused and enacted values and the core beliefs and assumptions

shared by institutional leaders, faculty, students, and other

constituents, such as alumni and parents” (1998, p. iv).

Much like culture in general, university culture is based on

shared values and belief systems that serve to convey a sense of

institutional identity, instill a commitment to the institution

rather than just oneself, shape and guide personal and

professional behavior, and foster stability in the overall

institution (Kuh and Whitt, 1998). Above all, “because

culture is bound to a context, every institution’s culture

is different” and unique (Kuh and Whitt, 1998, p. 13).

Because it holds the interests and traditions of the community in

high esteem sometimes institutional culture can conflict with

academic freedom. Occasionally, the research and teaching

interests of faculty members conflict with community norms.

Kuh and Whitt also describe three basic values pertaining to

college and universities and faculty. First is the

“pursuit and dissemination of knowledge as the purpose of

higher education. The primary responsibility of faculty members,

then, is to be learned and to convey this learning by means of

teaching, inquiry, and publication.” Second is the tenet

that faculty should have autonomy in the pursuit of their

academic work. And third, faculty must profess a belief in

collegiality and demonstrate this belief “in a community of

scholars that provides mutual support and opportunities for

social interaction and in faculty governance” (1998, p.

76). And, according to the American Association of University

Professors’ (AAUP) Statement on Academic Freedom, the

college professor has both freedom within the classroom and

freedom to research and publish on the subjects of his or her

choice (Hofstadter and Metzger, 1955).

The existence of a strong university culture can have both

positive and negative effects. The pressure to behave in ways

that are culturally acceptable may constrict innovation and

difference (Kuh and Whitt, 1998). Of more concern,

A dominant culture presents difficulties to newcomers or

members of underrepresented groups when trying to understand and

appreciate the nuances of behavior. At worst, culture can be an

alienating, ethnocentric force that goads members of a group,

sometimes out of fear and sometimes out of ignorance, to

reinforce their own beliefs while rejecting those of other groups

(Kuh and Whitt, 1998, p. 15).

What happens when a faculty member chooses not to agree with

society’s culture; or an institution’s culture; or a

department’s culture? How is this disagreement made

manifest in a visual way?

Disciplinary Culture

The culture of a faculty member’s discipline is the

primary source of faculty identity (Kuh and Whitt, 1998). For

example, Howard R. Bowen and Jack H. Schuster found that faculty

members of different disciplines exhibit diverse attitudes,

values, and personal traits (1998; Kuh and Whitt, 1998).

Likewise, Everett C. Ladd and Seymour M. Lipset found that

political and social attitudes differed across academic

disciplines (Ladd and Lipset, in Kuh and Whitt, 1998). For

example, the most liberal ideas and attitudes were expressed by

faculty in the social sciences and the most conservative by

professors in the applied professional fields.

Nationally, English department culture is known for being

volatile – a place where the “culture wars”

have taken place (and are still taking place depending upon the

institution). Some English departments have survived the war,

whereas others, such as Columbia University’s, have been

decimated. According to Mark Krupnick, a professor of literature

in the Divinity School (Note 2) at the University of Chicago, the typical

explanation for these “cultural wars” is a

combination of intellectual and political divisions:

First, starting with the invasion of French poststructuralism

in the 1960s, advanced literary interpretation changed from being

formalist in method and traditionalist in ideology to a brand of

French theory whose major distinguishing characteristics seemed

to be that it required you to spend more time reading the

theorist than reading the canonical texts of Western literature.

The second major explanation for the culture wars is that they

basically have been about politics, set off when ‘60s

radicals took their battles from the streets into university

departments (Krupnick, 2002, p. B16).

Of course, Krupnick's explanation is tinged with bias;

however, his perspective is not alone. Within the field of

English, there is much that has been written about the

“cultural wars” and their effect on the discipline of

English as a whole (Clausen, 1990; Dumont, 1982; Gates, 1992;

Gossett, 1994; Gregory, 1997; Heller, 1998; Krupnick, 2002;

Stimpson, 2002). Specifically, research has focused on the

factionalization and sometimes destruction of departments, the

effect of these factions on student learning, and the fractured

literary canon that has resulted. When visiting the individual

departments, we looked for signs of these national issues that

might appear on faculty doors.

Individual English Department Observations

To provide additional context for this paper, we have included

descriptions, based on departmental mission and our

observations.

Spelman College – Located in the recently built

Camille Olivia Hanks Cosby Academic Center, the English

department at Spelman College is “dedicated to the goal of

creating accomplished writers, critical thinkers, and effective

communicators.” The department is designed around a new

suite of offices. All of the furniture, carpeting, and artwork

are brand new. The hallways are bright and sunny and very

quiet. Most faculty members leave their doors just slightly

ajar; many are meeting with students. Although there are plenty

of desks and plenty of room for graduate students to work, most

of the desks are empty and unused. The receptionist’s area

is unstaffed and students use it as a work space.

Emory University – Located in Emory

University’s quadrangle of historic buildings, the English

department occupies three floors of the Calloway Memorial

Center. The department offers courses at both the graduate and

undergraduate level and has an interdisciplinary focus. The

halls are dark and very quiet. Few faculty members are in their

offices and most of the activity in the department takes place in

the graduate assistant offices.

Georgia State University – Located in the General

Classroom building, the English department is on the

9th floor. The walls are gray and many faculty

members do not have windows in their offices. The department is

bustling with activity: graduate students in conversation about

both academic and personal subjects, radios blaring the

day’s news (National Public Radio), and people constantly

coming and going. Georgia State doors were, in fact, more likely

to be open than those of the other institutions.

Faculty Doors: Common Themes

During our visits, we observed and photographed many common

elements in faculty door decorations. Some display items were

strictly functional; others were of a personal nature; and still

others were political, and seemingly unrelated to a

professor’s field of study. Most had more than one

purpose.

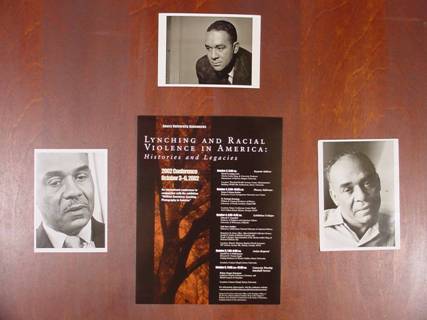

Certain items on faculty doors reflected city-wide cultural

events that were taking place at the time. For example, several

faculty members at all three institutions displayed a poster for

an interdisciplinary conference on lynching and racial violence

that was taking place at Emory University and other venues

throughout town. The conference was of interest to English

students because it included papers on African American

literature and lynching as well as poetry and drama events. The

conference had a strong political dimension; its timing

corresponded to a controversial exhibition of lynching

photographs that took place at the Martin Luther King, Jr.

Historical Site. Thus by displaying the poster, faculty members

were taking a specific stand on the value of not only viewing the

photographs but also publicly discussing the subject of lynching,

which for many has been taboo, especially in the South.

Not surprisingly, the largest number of posters for the

lynching conference was at Spelman, the historically black

college. In fact, there were more posters in the English

department at Spelman than at Emory where the conference took

place. The lynching poster exemplified a number of key themes

pertaining to faculty doors. One important use of door

decoration was to promote the activities of the discipline,

whether they were on campus or elsewhere in the community. For

example, several professors at both Emory and Spelman posted a

flyer for “Poetry at Tech” (the first annual Bourne

poetry reading at the Georgia Institute of Technology –

Georgia Tech). Other examples of discipline specific events

included a flyer for a reading by Pulitzer Prize winning poet

Yusef Kamunyakaa (Emory); and a student-produced play entitled

“What I Gave You” by Cassandra Henderson

(Spelman).

Like the aforementioned lynching poster, numerous other

postings on faculty doors had a political dimension. These were

related to the faculty members’ discipline in varying

degrees—some not at all. A posting that was discipline

related but even more specifically political than the lynching

poster was on the door of a female English professor at Georgia

State University. In this case, the posting took aim at a recent

Southern Baptists’ pronouncement relegating women to a

subordinate status. In a clever use of the literary past, the

counter argument was delivered by 18th century English

author and feminist Mary Wollstonecraft (Note 3) but framed as if quoted from a recent

interview: “Author Mary Wollstonecraft, contacted

recently, had this to say in response to the Southern

Baptists’ call for wives to submit to their husbands’

leadership.” The ensuing response was taken from an

18th century source. More tenuously connected to the

discipline of English is a Georgia State professor’s

posting of the famous photograph from Tiananmen Square showing a

lone protestor facing down tanks. This photograph sent a clear

message about individual freedom; its connection to free speech

(and hence to English) is discernable only when read in the

context of other materials posted on the same door. A nearby

photograph shows a library in ruins (apparently a bombed out

building from World War II). Together the images speak

eloquently about the political ramifications of free speech and

the exchange of information. Interestingly, this

professor’s vita contained nothing related to the political

concerns expressed on his door. Clearly the choice to include

these materials was a personal one.

Some doors displayed political messages that were not at all

connected to the study of English. For example, one faculty

member’s door at Emory consisted entirely of a large poster

with the headline “The Choice is Yours,” which

sounded an alarm about population growth in the United States.

This poster used demographic data in the form of line graphs to

advocate the curtailment of immigration (both legal and illegal)

– a position that was bound to be inflammatory for some

viewers. As there was nothing else posted on this door, the

statement stood out as strictly political; no other image or text

tied it to the professor’s discipline. Although this

professor’s research and writings were on middle English

women’s devotional literature, his service record as a

faculty member includes the presidency of Emory

University’s American Association of University Professors

(AAUP). This would seem to suggest a strong interest in

preserving his academic freedom and rights of self

expression.

Another category of materials not related to discipline was

calls for community involvement. For example, a professor at

Spelman posted a sign encouraging students to join Habitat for

Humanity. On this same door (and slightly more connected to

English) was a sign advertising “Teach for America”

with the headline “You Want to Change Things.” Also

at Spelman, another door had a sign advertising the Peace Corp

and participation in it. In many cases, these items promoted

community-related activities in which the professors themselves

were active participants (as noted on their curriculum

vitae).

Some items on the doors seemed to serve an aesthetic and a

practical purpose rather than conveying a direct message. For

example, doors at Spelman College all had a narrow vertical

window on them. Individual faculty members had, for the sake of

privacy, found innovative ways of covering these openings. One

faculty member coated the window with texturized material that

gave the appearance of frosted glass; on this she placed floral

appliqués. A similar approach was used by another Spelman

faculty member, but in this case the appliqué was an African

zigzag patterned cloth.

A third Spelman

professor carefully placed a series of postcards of art from a

variety of cultures (African and Japanese) on his window. These

decorations covered the maximum amount of window area but were

also centered and organized in a pattern that alternated darker

and lighter tones. Yet another Spelman faculty member plastered

her door window with movie images, including a poster for the

Kenneth Branagh film adaptation of Hamlet (discipline

related), and a close up of Denzel Washington’s face,

apparently from a poster for the movie Hurricane (this was

a lone black individual on a door populated mostly by white

figures from English literature).

For some faculty members, the arrangement of elements seemed

to be as important as what they chose to include. For example,

an Emory University professor who studies Ralph Ellison’s

impact and role in African American literature chose to display

photos of the famous author on his door. A group of three of

these photos was arranged in a symmetrical pattern with the

lynching poster in the center. The serene black

and white of the photos contrasted forcefully with the intense

reds of the lynching poster; this dichotomy was amplified by the

absence of any other materials on the door. Although the subject

was paramount, this professor had clearly given some thought to

aesthetics.

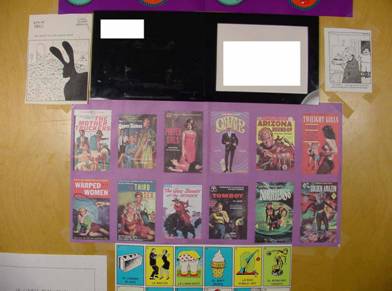

Another display that was of note for its aesthetic qualities

was found on the door of a Georgia State University professor.

This time, however, the selection of materials had no apparent

connection to the professor’s main field of interest, which

was Edmund Spenser, the English Renaissance poet. This faculty

member’s door adornments included samples of wrapping paper

designed by artist Ken Brown—the subject of which was

vintage homoerotic literature (“The Mother Truckers,”

“Nautipuss,” and “I Prefer Girls”).

Another wrapping paper design by the same artist

was a spoof of Spanish lotería cards. These also had a type

of bawdy humor (“La Lawn Butt,” “Los

Briefs,” and “La Day Old Meatloaf”). The paper

samples were brightly colored and arranged in a more or less

symmetrical pattern along with several cartoons. Like the

population control poster mentioned earlier, some of these

materials might be considered offensive – and not easily

justified by a connection to the discipline. But, the professors

in question clearly felt that they had a right to display them.

In fact, the Georgia State professor was eager to answer

questions about the images and talk about his related interests

in contemporary art.

Apparently, the materials displayed on this

professor’s door were a kind of personal pastime, and an

aspect of his personality that he wished to share with his

colleagues and students. Other faculty members in the department

encouraged us to view this specific door and include it in the

study. (Note 4)

Unlike the population control polemic displayed by the Emory

professor, this set of materials also had a humorous side; humor

was another major category of materials we observed. According

to R. Steven Schiavo’s research on faculty doors at

Wellesley College, 33% of the 60 faculty doors that he examined

had cartoons on them. When asked to react to these doors,

students thought the faculty behind them would be friendly,

humorous, and easy to approach (Schiavo and Miller, 1993). As

mentioned, there were cartoons placed among the wrapping paper

samples (Gary Larson’s Farside and Matt

Groening’s Life in Hell). Often professors would

combine humor with messages related to the discipline of

English. On the above-mentioned Life in Hell, for

example, the professor added the caption “The reason for

the passive voice” over a cartoon showing the signature

rabbit character explaining his messy room to the authority

figure with the words “Mistakes were made.” The

department chair at Georgia State also displayed a cartoon on his

door. Interested in American drama, this professor chose a

cartoon showing small children being prodded by their teacher to

perform the rather glum Arthur Miller play Death of a

Salesman: “O.K. Willy drag yourself to the table and

collapse in despair. Enter Biff.”

Among the other items faculty members chose to display were

family photos and artwork done by their own children. At Georgia

State, for example, one professor displayed a piece of artwork

with the caption “Hand’s print” and the name

Noah printed in child-like writing in the top left corner. This

faculty member placed the impression of his son’s hands at

a child’s eye level. Another door in the same department

featured a photograph of two of the professor’s children in

Halloween costumes. This photograph was secured by a souvenir

Beefeater clip from London. Such casual displays of family

materials were rare in the English department at Spelman College

and non-existent at Emory.

Finally, there were many items on faculty members’ doors

that were strictly functional. For example, numerous professors

at both Spelman and Georgia State placed envelopes or pockets on

their doors to distribute syllabi and student information. Among

the most elaborate was a Georgia State professor’s, which

consisted of a four-section plastic paper holder with one section

devoted to each of her classes. Spelman College doors were all

outfitted with slots to receive student papers. Also very common

at Spelman and Georgia State were postings of departmental events

and deadlines, registration information and office hours. These

items were noticeably absent from Emory’s English

department hallways.

Among the functional postings were many that assisted students

not only in their coursework but in their extracurricular

activities, and career plans as well. These were most common at

Spelman College and included a sign-up sheet for a film club, an

advertisement for a graduate student recruitment fair, a posting

for a Dow Jones Newspaper Fund internship, and a call for student

academic presentations entitled, “Food for Thought.”

Also common at Spelman were notices advertising the

accomplishments of current and past students. For example,

several professors’ doors featured an ad for the book,

Leaving Atlanta, by Spelman graduate Tayari Jones. In

addition, several faculty members posted copies of opinion

articles by students published in the Atlanta Journal

Constitution. The previously mentioned notice about the play

“What I Gave You” also advertised student work.

Again, this type of posting was very common at Spelman, less

common at Georgia State, and rare at Emory.

Faculty Doors and Institutional Culture

Certain patterns emerge in the decoration of the doors that

seem to reflect institutional differences. As mentioned earlier,

Spelman College’s mission was the most committed to

undergraduate education, and in particular, the preparation of

young black women for leadership roles. It was not surprising,

then, that Spelman doors contained the most material of use to

students: signup sheets, course handouts and the like, but above

all, postings that touted the accomplishments of current and

former students. These materials all spoke emphatically of the

professor’s responsibility to ensure the student’s

success in college and after. Every effort was made to provide

students with the information necessary for the completion of

their course work, and afterward, for job placement and

recognition of their career achievements. This commitment by

professors to the student’s well-being was borne out by

other aspects of Spelman’s curriculum as well. The authors

themselves had the chance to attend a mandatory assembly

featuring guest speaker Ertha Kit, whose colorful and upbeat

recollections were clearly intended to motivate and inspire her

audience. Other campus events, including art exhibitions, music

performances, and plays, were selected with the idea in mind of

highlighting the achievements of black women.

Although Georgia State’s doors also boasted an array of

student-oriented materials, what was most noticeable in this

department was the lively and idiosyncratic nature of the

postings there. Georgia State’s English department had more

humorous or witty decorations, and more material that expressed

highly personal concerns (e.g. the gay fetish wrapping paper).

This sensibility was complemented by the generally lively

atmosphere of the department. As mentioned earlier, Georgia

State’s hallways were the most active. Students and faculty

there seemed eager to give us directions and provide information.

Was this upbeat atmosphere a fact of institutional culture at

Georgia State? Was there a campus-wide push, similar to that of

Spelman, to create a friendly, student-oriented environment

there?

The authors’ knowledge of other departments at Georgia

State seems to suggest otherwise. Some were devoid of activity;

others had a policy of disallowing door displays. In fact Georgia

State was a large and diverse institution, and one whose mission

seemed to be in flux. Started as the evening commerce school for

the Georgia Institute of Technology, the institution had recently

been awarded research university status within the state and

within the new Carnegie Classifications. Unlike Spelman, Georgia

State lacked campus-wide agreement about the relative importance

of teaching versus research.

The atmosphere at Emory’s department of English was

considerably less lively. Although we visited all three

departments during the same time period, few of the Emory faculty

members were in their offices; we had trouble finding a student

to give us directions. Also notable at Emory was the

proliferation of political messages on doors. In addition to the

aforementioned population control poster, for example, there was

a bold-lettered notice condemning the voting irregularities of

the 2000 election, and questioning the legitimacy of the Bush

administration. On the other hand, Emory’s doors were

devoid of family pictures or artwork. It would be easy to infer,

based on these observations, a connection between the relatively

chilly atmosphere in Emory’s English department and the

confrontational nature of its postings. Similarly, one might

conclude that the lively and humorous character of the Georgia

State displays was tied to the upbeat atmosphere in that

school’s English department.

Such conclusions risk oversimplification, however. In fact,

the notion of academic freedom makes it likely that each

person’s door was first the product of his or her personal

agenda, and secondly that of the institution in which it was

situated. The definition of academic freedom is ambiguous and

conflicting: it pertains to the freedoms of the faculty, the

freedoms of institutions of higher education, and the freedoms of

students. However, the courts have interpreted academic freedom

to include the free exchange of ideas. Specifically, in

Keyishian v. Board of Regents, the Court noted, “The

nation’s future depends upon leaders trained through wide

exposure to that robust exchange of ideas which discovers truth

‘out of a multitude of tongues, [rather] than through any

kind of authoritative selection’” (385 U.S. 589, 603,

1967). Given this interpretation of academic freedom, it would

stand to reason that faculty should be free to place what they

want on their doors – the doors and their very presence in

the department act as a form of education and make a contribution

to the marketplace of ideas (Rabban, 2001).

Where does this freedom originate? According to Richard

Hofstadter and Walter P. Metzger, the traditions of the

university, including tenure, peer review, and shared governance,

place professors in a unique position with respect to their

institutions (Hofstadter and Metzger, 1955). Tenure, for example,

makes it unlikely that professors will be summarily dismissed for

expressing unorthodox views. An even more compelling reason for

faculty members’ job stability is their relative scarcity:

a university that fires a prolific and well-regarded academic has

no guarantee of finding a replacement, and does so at its own

peril. This enables each professor to behave as an independent

power center. The door to his or her office is the doorway to a

private realm—a place in which he or she is free to set a

teaching and research agenda without interference.

As mentioned earlier, English departments across the country

have suffered from the “culture wars”. However, we

saw very little direct visual evidence of these wars in the

departments we visited. Did the fact that one Georgia State

professor’s display of homoerotic wrapping paper faced

another’s poster advertising Shakespeare’s Much

Ado About Nothing indicate that the two individuals were

locked into disagreement about what should be included in the

literary canon? Most likely not – the academic interests

of the owner of the homoerotic wrapping paper (Edmund Spenser)

were as much a part of the Western literary canon as Shakespeare

was.

Faculty independence means that academic departments can and

must allow postings by individual members that may be offensive

to others. And, members of the department are expected to respond

to these postings in the spirit of academic freedom: if a

neighbor wishes to post inflammatory materials, they must not be

inflamed. For this reason, the presence of such materials is not

in-and-of-itself evidence of bad relationships within a

department.

Comparisons to Conceptual Art

Strongly individualistic visual displays, which are tied to

multiple agendas and understandable on multiple levels—this

describes faculty doors nicely, but in our minds could serve

equally well as a definition of art. Whence does such a

definition originate? In the past, few felt compelled to define

art, as it had a specific role to play within socio-economic and

religious systems. In the words of art critic Suzi Gablik

(1984), “Until we come to the modern epoch, all art had a

social significance and a social obligation” (p. 24).

Artists created works (as in the European Renaissance) at the

behest of wealthy patrons and religious leaders. Paintings and

sculptures adorned churches, for example, to instruct the

illiterate masses about religious belief. But during the modern

period (beginning in the late 19th century), art

“cut itself loose from its social moorings” and

became concerned with individual self-expression (Gablik, 1984.

p. 21). The essence of modern art – in particular, the

abstraction of the early to mid 20th century –

was unfettered exploration of the artist’s soul. Not tied

to a specific patron or social function, the artist’s role

came close to that of the professor which we described above: a

free agent pursuing his or her own creative agenda.

As modern abstraction exhausted itself during the early 1960s

(perhaps as a result of turning inward to the point of

solipsistic imprisonment), art again began to explore the social

conditions in which it existed – but this time without any

allegiance to a style or a tradition of art making. The modus

operandi of the new art was to blur the boundaries between art

and life (Haskell, 1984). It made use of every kind of source

material available and challenged every sacred cow of previous

art. Junk art vastly expanded the range of materials from which

an artist could draw. Pop art demolished the boundary between

high and low culture. Fluxus and performance art allowed chance

events to shape the work, taking away the requirement that art be

a fixed object (Haskell, 1984). (Note 5) Conceptual art challenged the notion that art

should be strictly retinal – that is to say, shun the

verbal and communicate through visual means only (Godfrey,

1998).

It is here that we can begin to connect visual art to faculty

door decorations. Compared to masterpieces of the past, of

course, faculty door decorations come up short. They are not one

of a kind, not made by a trained professional, and adhere to no

specific principle of craft and formal cohesion (Gablik, 1984).

They incorporate mass-produced materials, not created solely by

their owners. Being subject to change at any time, they are not

fixed objects to be passed on to the next generation. Nor can

they be bought or sold as commodities like Renaissance

portraits.

But it is precisely these factors that invite us to compare

faculty door decorations to contemporary art. Because recent art

(and especially conceptual art) discards the requirement that art

be a unique, enduring object, and accepts any imaginative use of

visual materials (including text), it prompts all kinds of

propositions about what might be entered in as art (Godfrey,

1998).

Among the early antecedents to conceptual art was Marcel

Duchamp’s “Fountain,” which, by placing an

ordinary urinal in an art gallery, asked whether it was the

context, not the form that made the work of art (Morgan, 1994).

This display by Duchamp, along with others such as an inverted

bicycle wheel, and hat-rack, were described as

“readymades”: mass produced objects, which in the

hands of the artist became vessels for cultural commentary. As

collections of decidedly non-art materials, faculty door

decorations, like readymades, operate strictly through

context.

As conceptual art evolved, it challenged typical notions of

art objects in other ways as well. For example, author Tony

Godfrey refers to a whole category of works as “anti-form

sculptures” based on their use of unpredictable or

changeable materials (Godfrey, 1998). Among these are Robert

Smithson’s earthworks, such as Asphalt Rundown from 1967.

In this work, the artist arranged for a dump truck to dump a load

of asphalt into an empty quarry near Rome, Italy. The art

consisted of whatever form was created by the process of the

asphalt falling down the wall. Other artists such as Rafael

Ferrer used ice or leaves—materials that were subject to

change during the life of the piece—to make art works that

changed as those materials decayed or melted.

Contemporary art, and in particular, conceptual art also

departed from past artistic traditions in its placement of text

on an equal footing with images. The modernism of the early to

mid twentieth century struggled to assert that art could speak

through shape, line, and color alone. Its language was

pre-verbal, and therefore universally understandable (Gablik,

1984). Conceptual art, on the other hand, conceded that words

were thoroughly intertwined with our visual language, and

embraced them as one of many possible means of expression.

According to artist Joseph Kosuth, “Fundamental to this

idea of art is the understanding of the linguistic nature of all

art propositions, be they past or present, and regardless of the

elements used in their construction” (Kosuth in Godfrey,

1998, p. 163). Hence the appearance of a whole category of works

that might be described as “text pieces:” items in

which text was used as a counterpoint to the imagery, or a

substitute for it. These include John Baldessari’s

paintings of text passages about the process of painting; Bruce

Nauman’s neon signs “Live and die, die and die, shit

and die, etc;” Adrian Piper’s racially provocative

images scrawled on New York Times covers; and Barbara

Kruger’s famous pairings of words with images from

advertising and popular culture: “I shop therefore I am;

“We don’t need another hero” (Godfrey, 1998).

In these cases, the art is less the object itself than the

proposition made by the text, or the juxtaposition of text and

image. In some cases this proposition is about the nature of art;

in others, the nature of life; and still others, it is

political.

Numerous faculty door decorations we observed could be

described as “text pieces.” Examples include the item

at Georgia State juxtaposing Mary Wollstonecraft’s words

with those of the Southern Baptists’ Convention; the clever

counterpoint of current news media with historical texts was akin

to the kind of feminist critique present in the works by artists

Barbara Kruger and Adrian Piper, mentioned above. Another

example was the overlay of the words “The reason for the

passive voice” on the Farside cartoon. Although it

certainly contained a caveat for the student about good and bad

writing, it also addressed widespread concerns about the

obfuscation of meaning (particularly in political discourse)

through fuzzy language. In these examples, faculty door

decorations also made “propositions” much like those

of contemporary art—only this time the subject was the

academic as well as the philosophical, phenomenological, and

political.

Conclusion

In his novel, The Corrections, Jonathan Franzen writes

(from the point of view of Chip, an English professor),

Through his open door Chip could see the door of Vendla

O’Fallon’s office. It was papered with healthful

images and adages—Betty Friedan in 1965, beaming Guatemalan

peasant women, a triumphant female soccer star, a Bass Ale poster

of Virginia Woolf, SUBVERT THE DOMINANT PARADIGM—that

reminded him, in a dreary way, of his old girlfriend Tori

Timmelman. His feeling about decorating doors was: What are we,

high-school kids? Are these our bedrooms? (Franzen, 2001, p. 49)

The departmental hallways we observed did not look like high

school lockers or teenagers’ bedrooms, however. Far from

being inane or immature, their decorations showed careful thought

and consideration. They attended to the needs of those around

them (as in the case of notices, and calls for participation),

but also embellished these materials in ways that elucidated the

significance of the academic endeavor in general. Nor did they

shrink from addressing controversial issues (although there is

still disagreement on the extent of faculty freedom to express

opinions outside of their field of expertise). If faculty door

decorations have the potential to show an individual

professor’s concerns, philosophy, and aspirations, then

this mode of expression may be a way to reach out to the

university community. Perhaps this is why, according to R.

Steven Schiavo’s research, faculty with richly decorated

doors are more likely to be described by students as

“friendly” (Schiavo, Madaffari, and Millier, 1999).

Far from being pretentious (as one professor who did not want to

participate in our study asserted) door decorations indicate a

desire to embody through succinct, visual means (very much in the

mode of contemporary art), what is expressed at length in a

professor’s research, teaching, and service. In other

words, they are an auxiliary channel of communication for a

faculty member, whose work frequently gets lost in the sometimes

arcane world of scholarly journal articles. Like art, the

decorations operate as an organic entity: they are complex,

subject to change, and open to interpretation by different

viewers (Kuh and Whitt, 1998; Schein, 1984). Each viewer is free

to draw his or her own conclusions. Nevertheless, faculty doors

are a key element in the academic environment and should be

carefully considered by anyone wishing to understand the culture

and dynamics of an academic department. The one thing to be said

about faculty door decorations is that they are not one thing

– they reflect and add to departmental culture, communicate

ideas, inspire thought, and challenge their viewers.

Notes

1. Currently the

authors have proposals under consideration for the presentation

of such an installation at galleries in Atlanta and

Philadelphia.

2. Mark Krupnick

was once in the English department at the University of Chicago

but “jumped ship” to take a position in religion and

literature in the Divinity School in 1990.

3. Mary

Wollstonecraft was an early advocate of equal education for

women, and she penned the Vindication of the Rights of Women

(1792) often cited as the first great feminist document.

4. However, we

chose not to pinpoint specific individuals and instead relied on

faculty members to contact us after receiving our initial

invitation to participate in the project. This professor

contacted us on his own initiative.

5. An early

antecedent is John Cage’s music (e.g., 4’ 33”

in which a pianist sits silently for the duration of the piece

and the music is whatever background noise occurs during that

time).

References

Altman, I. (1975).The environment and social behavior:

Privacy, personal space, territory, crowding. California:

Brooks/Cole Publishing Company.

Barthes, R. (1957). Mythologies. New York: Hill and

Wang.

Barthes, R. (1977). Image, music, text. New York: Hill

and Wang.

Becher, T. (1981). Toward a definition of disciplinary

cultures. Studies in Higher Education 6, pp. 109-122.

Becher, T. (1994). The significance of disciplinary

differences. Studies in Higher Education 19, no. 2, pp.

151-161.

Bowen, H. R. and Schuster, J. H. (1986). American

professors: A national resource imperiled. New York: Oxford

University Press.

Brazzell, J. C. (January-February, 1992). Bricks without

straw: Missionary-sponsored black higher education in the

post-emancipation era. Journal of Higher Education 63,

no. 1, pp. 26-49.

Chace, W. (2002). Presidential welcome. Emory University

website. Accessed via Internet on May 9, 2002, www.emory.edu/PRESIDENT.

Clausen, C. (Spring 1990). ‘Canon,’ theme and

code. Southwest Review 75, no. 2, pp. 264-280.

Cox, E. (1985). Spelman College is tying it all together

through the living-learning program. Paper presented to the

Annual Meeting of the National Association of Student Personnel

Administrators.

Dumont, R. (1982). The failure of college and university

English departments. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of

the Conference on College Composition, San Francisco,

California.

Edelman, M. W. (Spring, 2000). Spelman College: A safe haven

for a young black woman. Journal of Blacks in Higher

Education 27, pp. 188-123.

English, T. H. (1966). Emory University, 1915-1965, a

semicentennial history. Atlanta: Emory University.

Flanders, B. H. (1995). A new frontier in education: The

story of the Atlanta Division University of Georgia. Atlanta:

University of Georgia Press.

Foucault, M. (1986). In N. Mirzoeff (1998). (Ed.). The

visual culture reader. New York: Routledge.

Franzen, J. (2001). The corrections. New York: Farrar,

Straus, and Giroux.

Gablik, S. (1984). Has modernism failed? London:

Thames and Hudson.

Gates, H. L. (1992). Loose canons. Notes on the culture

wars. New York: Oxford University Press.

Georgia State In-Depth, Georgia State University Website.

Accessed via Internet on May 9, 2002, www.gsu.edu/~wwwprs.

Godfrey, T. (1998).Conceptual art. London: Phaidon.

Gossett, S. (Fall 1994). Reimagining English departments: What

is our future? ADE Bulletin 108, pp. 34-37.

Greenbaum, P. E. and S. D. Greenbaum. (1981). Territorial

personalization: Group identity and social interaction in

Slavic-American neighborhoods. Environment and Behavior

13, pp. 574-589.

Gregory, J. (1997). American literature and the culture

wars. New York: Cornell University Press.

Guy-Sheftall, B. (1982). Black women and higher education:

Spelman and Bennett colleges revisited. Journal of Negro

Education 51, no. 3, pp. 278-287.

Hansen, W. B. and Altman, I. (1976). Decorating personal

places: A descriptive analysis. Environment and Behavior

8, pp. 491-504.

Haskell, B. (1984). Blam! The explosion of pop, minimalism,

and performance, 1958-1964. New York: Whitney Museum of

Art.

Heller, S. (August 3, 1988). Some English departments are

giving undergraduates grounding in new literary and critical

theory. The Chronicle of Higher Education 34, no. 47, pp.

A15-17.

Hofstader, R. Academic freedom in the age of the

college. New York: Columbia University.

Hofstadter, R. and Metzger, W. P. (1955). The development

of academic freedom in the United States. New York: Columbia

University.

Kaye, H. J. and Galt, A. H. (February 8, 2002). It’s not

just an office, it’s a vessel of self-expression. The

Chronicle of Higher Education, pp. B16-B17.

Keyishian v. Board of Regents, 385 U. S. 589, at 603

(1967).

Kosuth, J. (1998). In T. Godfrey. Conceptual art.

London: Phaidon.

Krupnick, M. (September 20, 2002). Why are English departments

sill fighting the culture wars? The Chronicle of Higher

Education, point of view.

Kuh, G. D. and E. J. Whitt (1998). The invisible tapestry.

Culture in American colleges and universities. ASHE-ERIC

Higher Education Reports, No. 1, Washington, D.C.: ASHE.

Ladd, E. C. and. Lipset, S. M. (1976). The Ladd-Lipset survey.

In G. D. Kuh and E. J. Whitt (1998). The invisible tapestry.

Culture in American colleges and universities. ASHE-ERIC

Higher Education Reports, No. 1. Washington, D.C.: ASHE.

Metzger, W. P. (1961). Academic freedom in the age of the

university. New York: Columbia University.

Morgan, R. C. (1994). Conceptual art. Jefferson, North

Carolina: McFarland and Company, Inc.).

Rabban, D. (November-December, 2001). Academic freedom,

individual or institutional? Academe 87, no. 6, pp.

16-20.

Rhoads, R. A. and W. G. Tierney. (1992). Cultural

leadership in higher education. University Park,

Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University, National Center on

Postsecondary Teaching, Learning, and Assessment. (ED 357

708).

Ruscio, K. P. (1987). Many sectors, many professions. In B.

Clark. (Ed.). The academic profession. Berkeley:

University of California Press.

Schiavo, R. S. and J. W. Miller (1993). Personalization of

faculty offices. Paper presented at the American Psychological

Association Annul Meeting, Toronto, Canada.

Schiavo, R. S., Miller, J. W. and T. M. I. Madaffari. (1998).

Personalization of faculty office doors. Paper presented at the

Eastern Psychological Association, Boston, Mass.

Schiavo, R. S., Madaffari, T. M. I. and J. W. Miller. (1999).

Professors’ office door decorations: What do they tell?

Paper presented at the American Psychological Association Annual

Meeting, Boston, Mass.

Schein, E. (1984). Coming to a new awareness of organizational

culture. Sloan Management Review 25, no. 2, pp. 3-16.

Williamson, J. (1978). Decoding Advertisements. Ideology

and Meaning in Advertising. London: Marion Boyars.

About the Authors

Marybeth Gasman is an assistant professor of higher

education at the University of Pennsylvania. Her research

pertains to the history of black colleges and African American

philanthropy.

Edward Epstein is a professional artist in the city of

Philadelphia. His paintings observe everyday phenomena and

experiences and often uncover political and social themes.

|